|

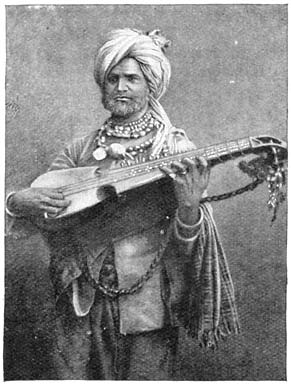

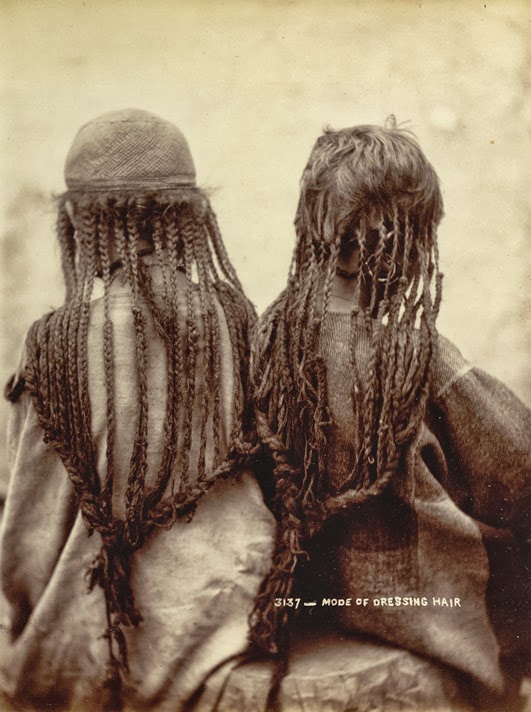

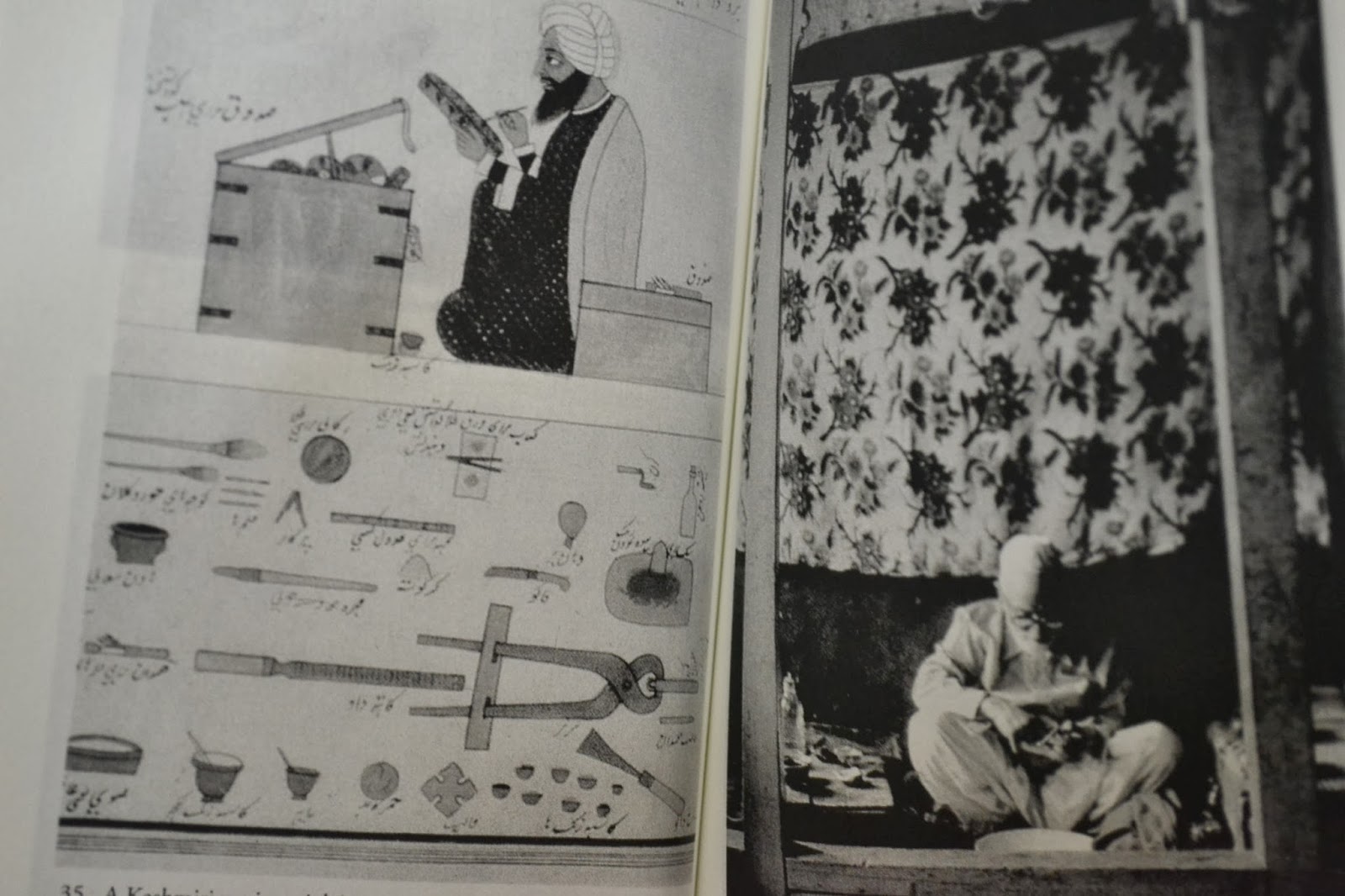

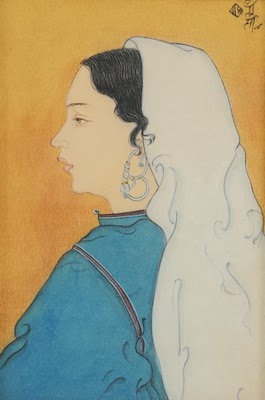

Krishna Boya Greb, Kashmiri Minstrel, 1911

(seems to be holding a ‘dutar’) |

Although the singing traditions of Kashmir are usually associated with Kashmiri Muslims but around hundred years ago, a visitor to Kashmir could run into a thriving community of Pandit singers too.

Yet, the only documented record of them comes from a few pages in a work titled ‘Thirty Songs from the Panjab and Kashmir’ (1913) by Ratan Devi and Ananda Coomaraswamy.

In 1911, while collecting Kashmiri songs in valley, they found that:

“Kashmiri Pandits are rarely musicians: those who are, claim to sing in many rags and talk boastfully of Kashmir as the original source of the music of Hindustan reckoning Kashmir another country, and not a part of India.

We heard three Pandit singers of some reputation, all old men. As accompaniment to the voice they use a small and rather toneless sitar. One also played on a zither (independently, not as an accompaniment), striking the many strings (tuned with much difficulty), with small wooden hammers held in both hands, making a sweet tinkling music. We were told that this Pandit was accustomed to sing to sick people, and even effect cures, but to our thinking, he sang no better than the others, that is, not very well. The so-called various rags sung by the Pandits are all very much alike, and musically distinctly uninteresting. The only song which seemed to us all worth recording was the following “Invocation to Ganesh” sung by Krishna Boya Greb, Pandit, son of Vasu Dev Boya Greb, to a sitar accompaniment. This very slow, rather hymn-like tune, if imagined to be sung in a rather nasal and drawling voice, will give a good idea of the general type of Pandit songs, expect as regards the words, which are exceptional. The curious actable staccato does not appear in any other Kashmiri song here recorded.

Invocation to Ganesh

Tsara tsar chhuk parmisharo

Rachhtam pananen padan tal

Gaza-mokha balaptsandra lambo-dara

Venayeko boyinai jai

Hara-mokha darshun dittam ishara

Rachhtam pananen padan tal

Translation [one Pandit Samsara Chand helped with the text, but the translation are all mostly flawed]:

Thou art all that moves or moves not, Supreme Lord!

The sole of Thy foot be my shelter!

Gaja-mukha, Bala-chandra, Lambo-dara,

Vinayaka, I cry Thee ‘Victory’!

In all wise show me They face, O Lord!

The sole of Thy foot be my shelter!

Some other Pandit songs:

Love Song

As nai visiye myon hiu kas go

yas gau masvale gonde hawao

Zune dabi bhitui dari chhas thas gom

Zonamzi osh ma angan tsav

yar ne deshan volingi tsas gom

yas gau masvale gonde hawao

Do not mock, my friend (f.); had it befallen another like me,

That fair flower had been a plume in the wind!

As I sat on the moonlit balcony, he came to the door;

I learnt that my lover had come to my courtyard,

If I meet not my darling (m.) I shall suffer heart-pangs

That fair flower had been a plume in the wind!

[There are a bunch of other songs given in the book by the only one I could easily recognise was the ‘Spring Song’ for its refrain Yid aye…(Eid has come)]

Yid ay bag fel yosman

Karayo kosmanan krav

Yid ay bag fel yosman

Nirit goham vanan

Yut kya tse chhuyo chavo

Trovit tsulhama mosman

karyo kosmanan krav

-0-

And yes, Pandits still lay claim on giving India

Natya Shastra, or at least giving the most authoritative commentary on it through Abhinavagupta.

-0-

Previously: