|

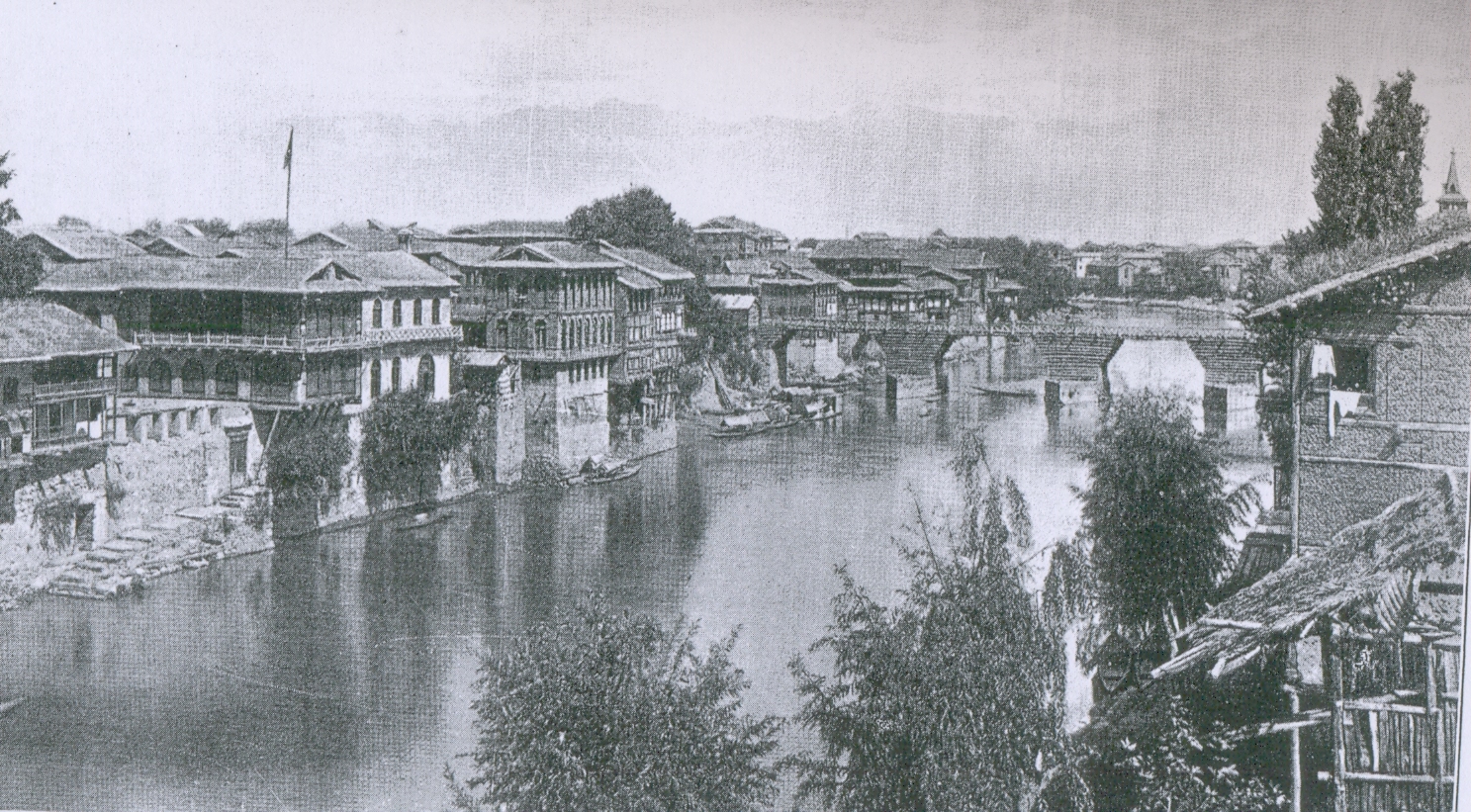

Puj Waan

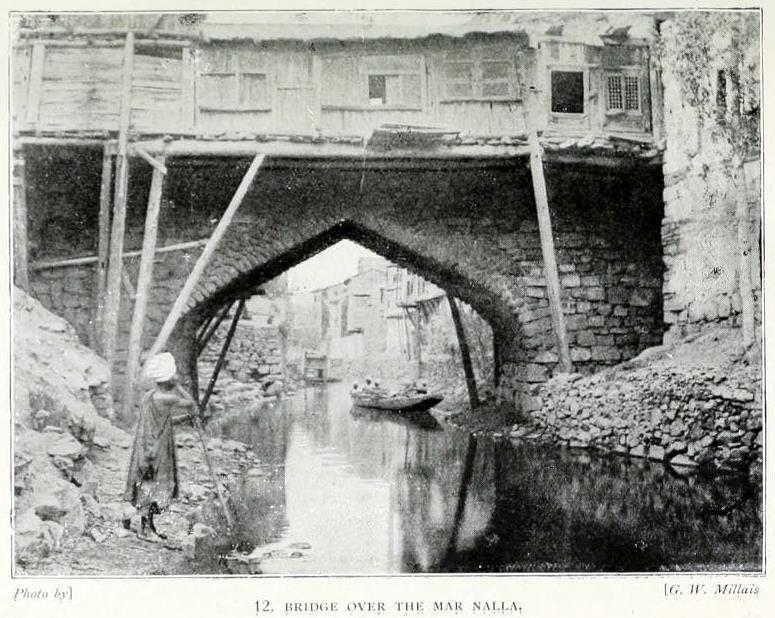

Kani Kadal

Srinagar

2008 |

As told by a grandaunt.

Ram Joo made his living in an odd way. He worked for municipality. His job was to visit slaughterhouses and stamp the dead animals with seals of approval in ink, declaring them fit or unfit for human consumption. A sensitive man, it is said the violence of his job eventually drove him mad. While stamping the dead sheep he took to singing to them, asking them:

Kat’a Kha’sh Kya’zi Kor’voy

Hai K’yah Gh’oom

Kat’a Mash Kosho’ya

Hai K’yah Gh’oom

Kat’a Kalas chuya doon

Hai K’yah Gh’oom

Sheep, why did they slay you?

Oh, what it did to me!

Sheep, have they sheared you?

Oh, what it did to me!

Sheep, is your head aching?

Oh, what it did to me!

The neighbourhood kids took to teasing him with the same lines. A sensitive man, it is said the experience eventually made him a saint. Around Habba Kadal area, he came to be known as Ram Joo Tabardar – Ram Joo the Woodcutter.

-0-

A note on an interesting word and a phenomena. Picked from an Uncle.

Slaughterhouses and the areas around them tend to have a peculiar smell that may offend most people visiting. But the people living in the area never notice it. In Srinagar, slaughter houses were around Chotta Bazaar area. The people living in that area never noticed the smell. They had developed a gaenz’nas – meaning their nose had got numb to the stink.

-0-

Aside: Earlier this year caught one of the most famous documentaries on the subject of animal slaughter, considered a milestone in the history of realistic documentary film making, ‘Le Sang des Bêtes’ by Georges Franju (Blood of the Beasts, French, 1949). [link, avoid if you are too sensitive]. A film that isn’t completely repulsive because it wasn’t made in color. It is not known if any saints were born in France after the film came out.

-0-

Complete song added by Narinder Safaya, Ram Joo’s grandson. He adds [via FB]:

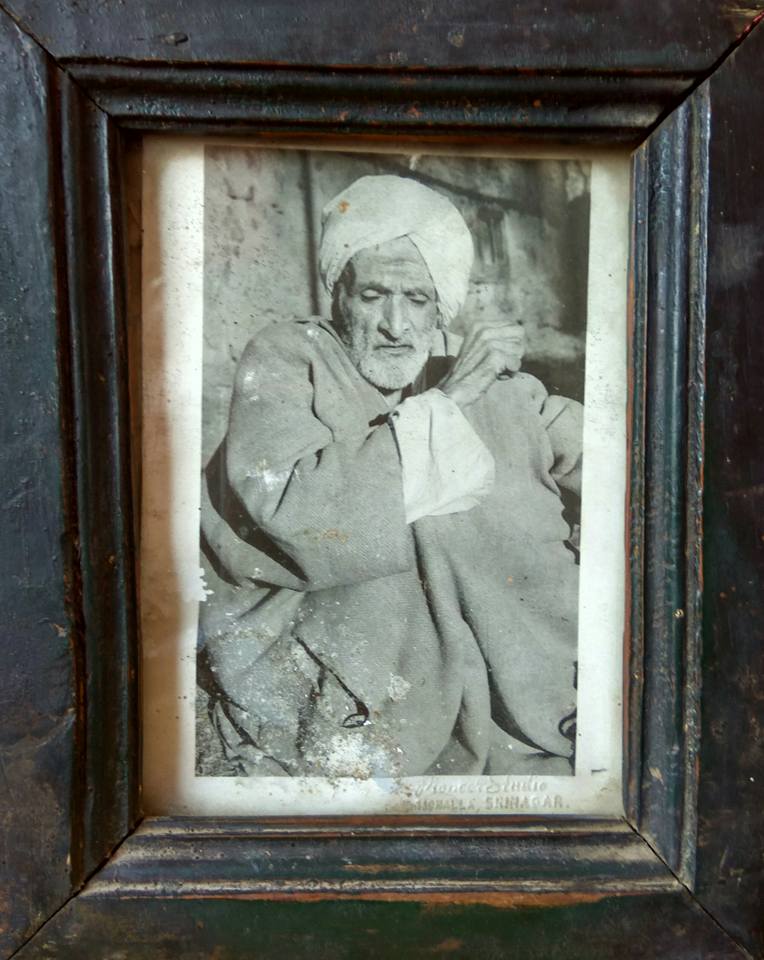

He [Ram Joo] had joined Srinagar Municipality around 1920. He was happily married, sired 4 children , three sons and one daughter. He worked as sanitary inspector for fifteen years. He was a spiritual person. He abandoned the job for reason stated by you. For this he was also teased as Ram Joo Maskas. He abandoned his family. His wife probably died of tuberculosis the same year when Kamla Nehru succumbed to T B in Switzerland [1936]. It said in our family she died of “HeH”. His children were taken care of his younger brother.Pt Shyam Lal Safaya (Taberdar) . We are from Chinkral Mohalla are known as Taberdars. My great great great grandfather Pt. Ganesh Dass Safaya got the nickname Taberdar as he had a partner who was Taberdar and he had been taken by him as partner in supply of fire wood business to the city dwellers through river by boats known as Bahech [Cargo boats]. In 1960 or 61 when I was 8/9 years old I remember Ram Joo came one day, took tea and left. For five years we could not trace him. Ultimately my father traced him living in Rock Temple Tiruchirapalli.

|

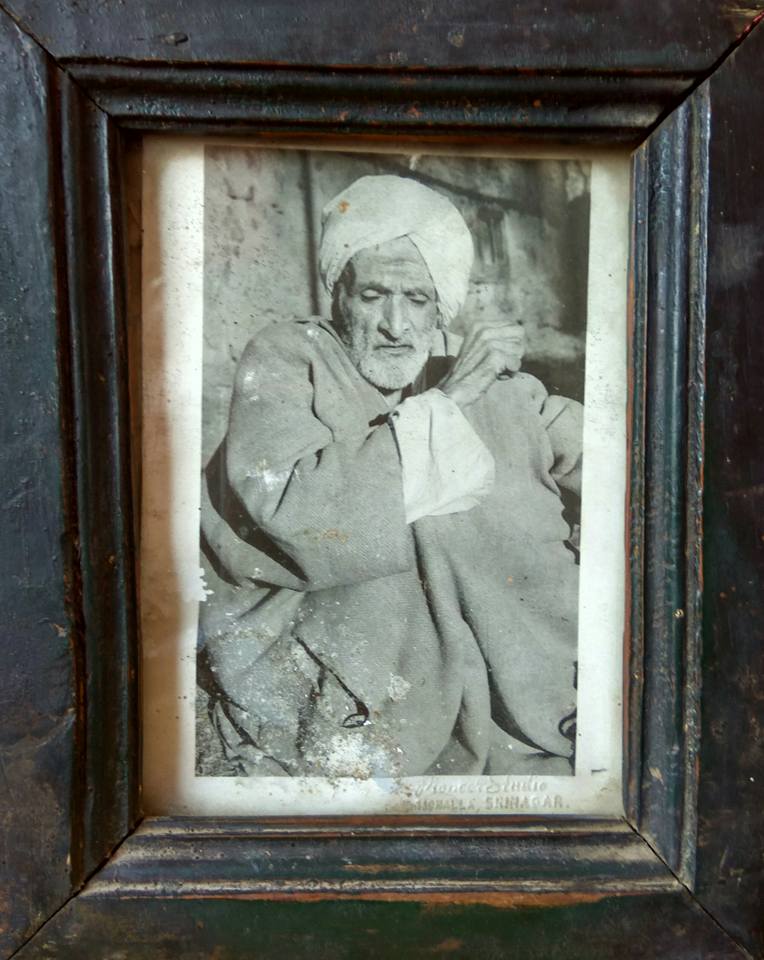

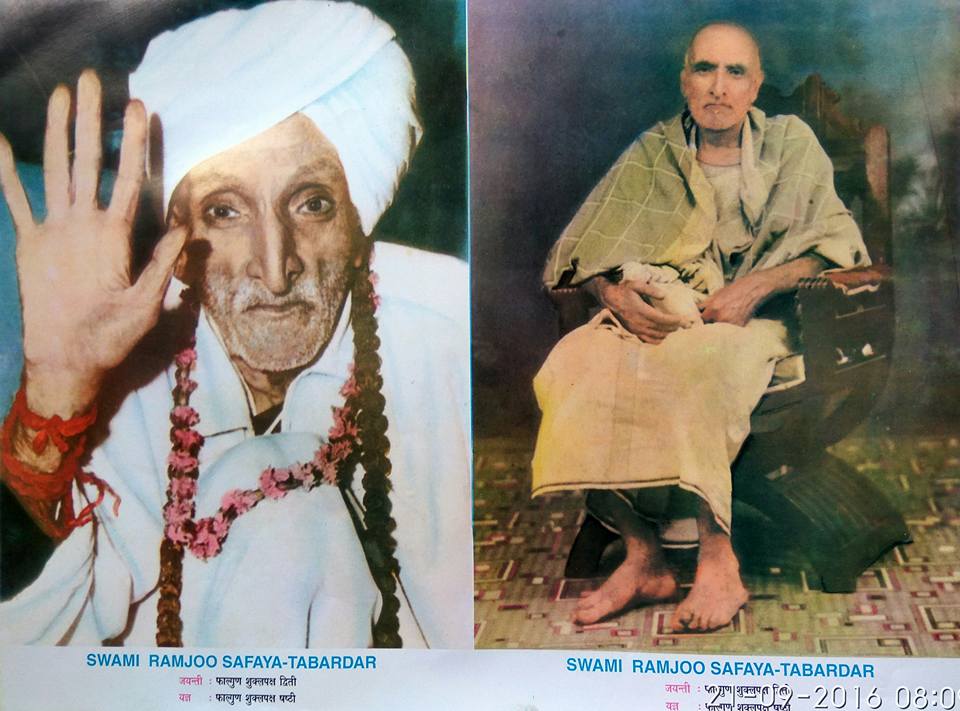

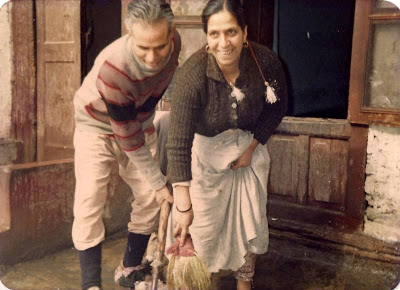

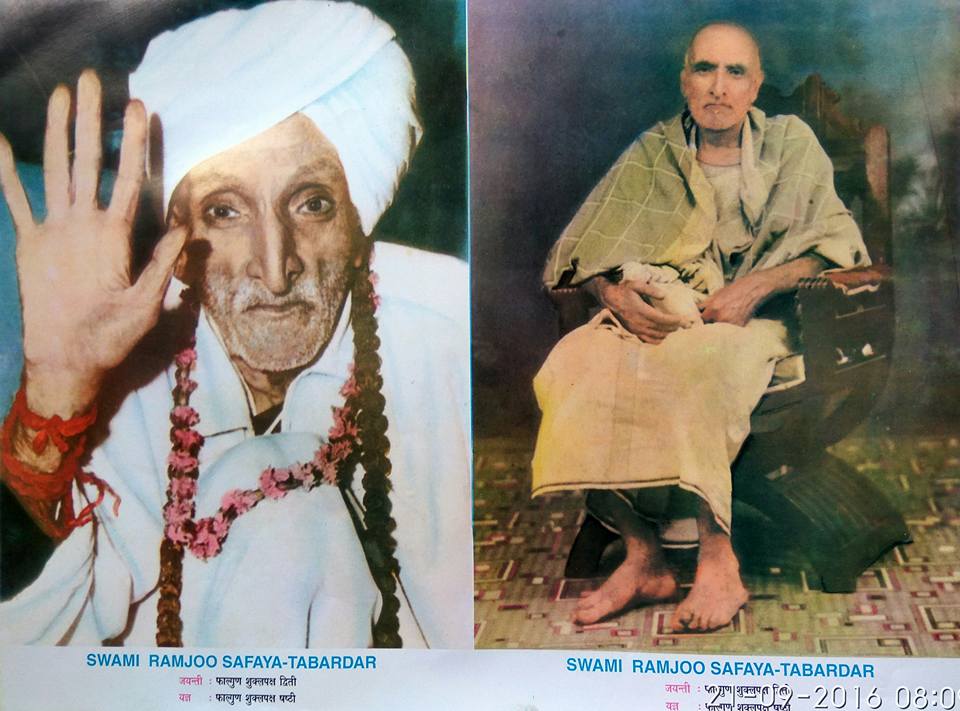

| 1.Four days before Nirwana 2.During his eight years stay at Rock Temple, Tricinapali, T.N. |

|

| After return from Tricy.TN. |

|

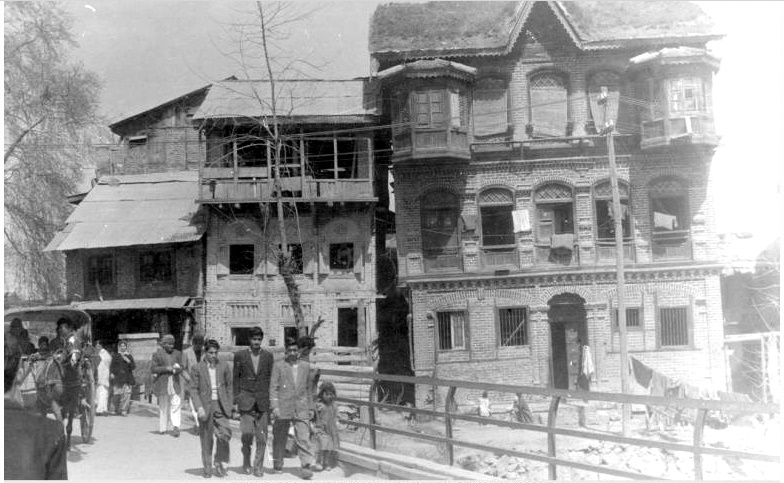

| The house at Chinkral Mohalla |

Story of “Taberdar house” at Chinkral Mohalla Srinagar by Narinder Safaya ji as told in 2013:

” It is about 200 years old. One Pt. Sukh Ram Safaya was a minister with one of the Afghan Rulers. He had a sister who was married to the son of a big landlord in Marraz (now district Anantnag). The woman was very beautiful. From this marriage she had a son. The local Afghan governor of the area had an eye on her. For protection, she was sent in the dark of night by her husband to her brother’s house. Her husband was killed by the said local governor. As Sukh Ram Safaya was very influential revenue collector, nothing bad happened to him. The woman stayed with the brother after being widowed. The child, Nank Chand, grew up under the protection of his maternal uncle and as such came to be known as Nank Chand Safaya. His uncle gave this house to him. Nank chand’s son was Pt.Ganesh Dass Safaya Taberdar, grand father of Swami Ram Joo Taberdar. In the last decade of 19th century, the upper storey got gutted and was rebuild by Pt.Ganesh Dass. We added a floor to it in 1970 and changed the roof to tin from birch and soil. From our kani we could see a ring of mountains which cover the entire valley.”

17th May, 2025

It is with deep sadness that I note the passing of Narinder Safaya ji yesterday. He first contributed to SearchKashmir back in 2013. In Delhi, he fostered connections among people with roots in Kashmir through “baithak” meets. Over the years, we discussed Kashmiri songs; he suggested songs for coverage and provided helpful corrections and advice regarding music and videos. A poet who wrote in Kashmiri, he appreciated any attempt to promote its use among the young. He remained supportive, even knowing more and understanding the struggles young people sometimes faced with pronunciation or word accuracy. His critique was always delivered with a sense of humor. One year, he promptly sent me the route for a walking temple tour in Srinagar via messages and another year shared books on Kashmiri Ramayan from his personal collection, which are now part of Archive project. He connected people with one another, serving as a unifying force, always with a smile. He will be missed.