Sometime History teases us with waggish little tales that make up this world and its present complexities. In fact, it often does that. You just have to read.

This is the funny little story of how the first government sponsored Madarsa for Kashmiri Muslims opened in the state, a school for the rich; the odd consequence of a Pathan sending his sons to read English language.

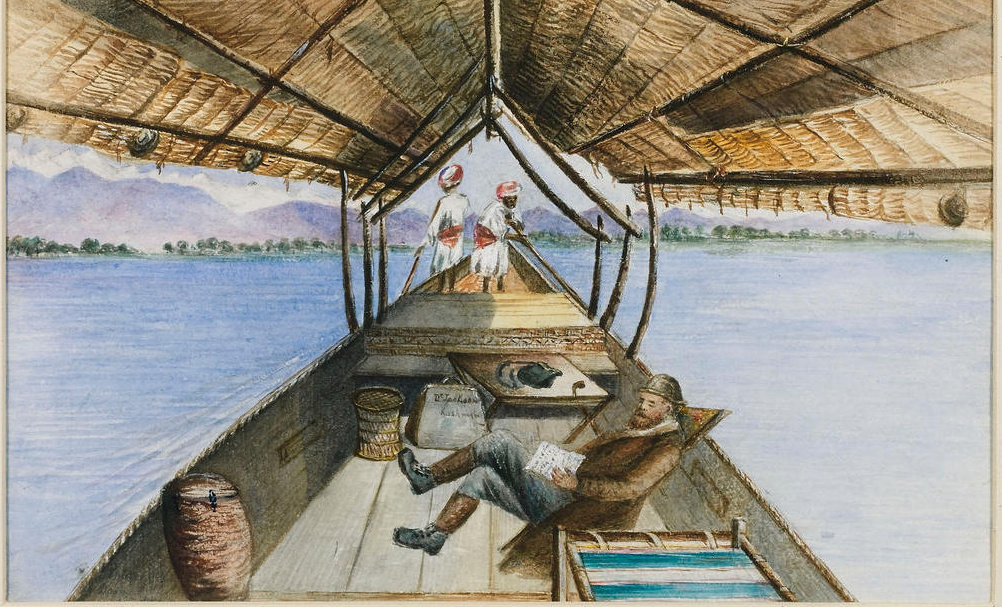

The story is told by W.J. Elmslie, the first medical missionary in Kashmir who after facing much difficulties and harassments did manage to operate in the kingdom, and her burning yearning of Christian pity to save souls for heavenly Lord did sow some seeds of good christians in what was then considered most fertile land for such deeds in the Empire. Also, during his five years in Kashmir he discovered what came to be coined as ‘Kangir Cancer’, and driven by his problems at communicating with natives, Elmslie was the first to compile a proper guide to Kashmir Vocabulary for future visitors [published in 1872, here].

The incident of interest happened during Elmslie’s fourth year in Kashmir, an account of which appears in a letter he wrote to his mother and dated 6th May, 1868. The letter appears in his biography written by his wife, ‘Seedtime in Kashmir: a memoir of W.J. Elmslie by his widow and W. B. Thomson’ published in 1875. In the letter he excitingly tells his mother:

“A little progress is being made in the valley. The first school established in Kashmir by the Maharajah has just been opened. Its history is the following. The father of the family of which I have already spoken, was particularly desirous that his two sons, two very fine lads, should learn a little English. He asked me if I would teach them. I said I had not time to do so, for my medical and other duties; but I would allow one of my assistants, who knew a little English, to teach his sons. One of the two lads has been very regular in his attendance, and has made some progress. A report of all this was carried to the Diwan, the Maharajah’s representative in the valley. Thereafter, a vigorous effort was made to get the father to give up sending his son to the mission bungalow to learn English. The effort failed, however. The father, I must tell you, is a Pathan, and is not so much afraid of the Kashmir Government as indigenous Kashmiris generally are. The Maharajah, in due time, received a full account of all that was going on; and His Highness, after some time, gave orders for the opening of a school for the teaching of Arabic, and desired the Diwan to try to prevail upon Sher Ali, my Pathan friend, to desist from sending his sons to the Doctor Sahib to receive instruction in English. In this effort, I am happy to say, the Diwan has failed. The boys came daily to us. This class for Arabic, got up primarily to decoy Sher Ali’s sons away from us, is the first Government school the valley has seen during the reign of Gulab Singh and his son, the present Maharajah. The class, I am told, is intended exclusively for sons of those who may be called the nobility of Kashmir. It is a pity the language was not Persian, and the school intended for any who was willing to attend. This is trying to boil the kettle from above.”

-0-