Tawi River.

6 May, 2011

-0-

Next couple of posts will be dedicated to Jammu.

in bits and pieces

Tawi River.

6 May, 2011

-0-

Next couple of posts will be dedicated to Jammu.

From Baburao Patel’s Q/A section in FilmIndia, August 1947 issue. ( via a collection shared with me by Memsaab Greta)

Lot of thinking going on there (what’s that thing about J.P ji ) but I am amazed by question posed by O.N. Thassu of Srinagar, whose progenies probably now live in Bombay and would probably readily buy the answer from Baburao Patel of Bombay (we know who else bought that answer only a year later endorsing it in a Court trail about a murder). Baburao Patel was known not only for his biting wit but ‘let’s bite some, any heads’ attitude towards what he considered blackheads on Bhart Mata’s beautiful face. He voiced opinions what would probably now be considered concerns of pragmatic-Hindu-middle-class. And he often did it in a very pragmatic Indian way, this particular (and many around that that) issue was in fact full of eulogies in praise of Gandhi. A pragmatic: He had Muslim friends, a fairly large readership (at least in the beginning) consisting of Muslims, naturally he was an expert at defining difference between ‘good nationalist Muslim’ and ‘bad Muslim’, he was a good Hindu, naturally he knew a thing or two about similarity between ‘good nationalist Hindu’ and ‘good Hindu’, he liked-dis-liked Nehru, liked-dis-liked Gandhi, liked, thought highly of Sardar Patel, liked Bose (as he believed ‘dead don’t disappoint’). One could say that naturally qualifies him for the modern ‘thinking Hindu’ type of our mundane times. But to his credit he was also open to criticism, and would often allow this criticism on his own platform. That certainly is not a modern trait. Still, it does not surprise that he was one of the first journalists to join politics and get elected to Lok Sabha on a ticket from Bhartiya Jan Sangh, the old avatar of ‘Bhartiya Janata Party’ – the platform, in its best form, advertised as a place for sensible Hindus with a burning love for the burning country.

Knowing Kashmiri attitude towards written word, and knowing the writings of Baburao, it should not surprise anyone that in early 50s, maybe to the much annoyance of Thassu Saheb, FilmIndia was banned in Kashmir. And it should not equally surprise anyone that the he actually thought of Kashmirs as lazy buggers, back-stabbers and that India would be lot better without Kashmir, and that his ‘Indian Muslim Brother’ would have (pose?) no problem. Now where have we heard that pragmatic solution and views before in recent times.

Time a quite a thing.

From being the pioneer of film journalism, by 1970s Baburao Patel, his FilmIndia run-over by Filmfare, was running a publication called ‘Mother India’ (a copy of which I have managed to get my hands on) and in it selling slogans like ‘Hindus of the world arise’, ‘Stop it mod-women’ and in between these slogans he was selling all kind of ayurvedic churans for every known human disease.

All said and done, I would not have been surprised if on any other day, in any other situation, to any other question, Baburao Patel would have simply told Thassu Saheb of Srinagar, ‘My friend, it is well-known advise, never take the advise of a man who at the end of the day is selling you a magic Churan of his own make.’

-0-

I did a post about the song, it remains one of the most popular post at this blog. Someone would occasionally ask for the lyrics. Although this was one of the few Kashmiri songs that I actually understood, at least if in parts, I found it tough to write down the lyrics to this song. I have seen even old folks struggle with some words while listening to these old folk songs, and occasionally going ‘Aaa’ on figuring out some twist of phrase.

These ‘Aas’ and ‘Ahhs’ remain private joys and despairs, I believed. My belief was wrong.

Last night, I came across the lyrics to the song and the name of its composer in a little book called ‘Kashmiri Lyrics’ (first published in 1945) by J.L. Kaul, revised and edited by Neerja Mattoo (2008). [Original edition , free Download here]

The song was written by Abdul Ahad Nazim (1807-65) also known as Waiz Shah Nur-ud-din , considered the finest nat writer of Kashmir (that would explain the religious intonations at the beginning of popularly sung version of the composition).

Lyrics.

yim zar vanahas bardar

karsana su yar boze

ya tui khanjar ta mare

na ta sani shabha roze

mas dyutnam kalavalan

chivaravnas akiy pyalan

chum duri ruzith zalan

karsana dava soze

kya mati goy myon kinay

atish bortham sinay

ashakh kamisana dinay

marun rava roze

bithith khalvath khanas

mushtakh panay panas

ashakh manz varanas

mashokh tanha roze

bulbul bihith ba gul

mushtakh az gul bilkul

nay rozi bulbul ta nay gul

akh lola kathah roze

kya mati karitham sitam

Nizam chu praran yitam

chus tashna darshun ditam

yi dam na pagah roze

Neerja Mattoo’s translation:

At his threshold my wailing I would utter,

O when will my love listen to me? –

I would that he did slay me,

Or else requite my love

The brewer of love gave me a cup of wine,

A single cup made me delirious and drunken,

I could not contain myself for joy;

But now he keeps off and causes me pain –

O when will he give me another draught

of the wine of love?

Love, why are you angry with me?

You have filled my breast with the smart of love.

Is it fair to let me suffer and die?

Alone, in a lonely tower,

the beloved sits, unconcerned for love;

while the lover roams desolate plains,

Will the beloved keep aloof from him?

The bulbul nestles close to the rose,

Doting in it and deep in love;

soon the bulbul and the roses die,

only a memory of love remains.

How cruel you have been to me!

Athirst for love, I am waiting for you

O come and show yourself –

This hour won’t last,

tomorrow brings another day

-0-

I’ve made a pact with the Lord about becoming the most perfect man on earth . . . remade so that I might compose perfect poems on the beauty of God. . . . I am the Great Weaver from Kashmir.” Well, then. “I think you might have lost your marbles,” says Dilja.

~’The Great Weaver From Kashmir‘ or ‘Vefarinn Mikli frá Kasmír’ (1927) by Icelandic novelist Halldór Laxness.

-0-

Image: Man weaving cashmere shawl (1924). via New York State Archives.

The thing about crossroads is that hardly anybody gets fantastically airdropped at a crossroad. One arrives at a crossroad by following a certain path. A person stuck at cross road is likely to benefit a lot by contemplating on the path taken, perhaps give a thought to the journey so far.

The thing about crossroads is that hardly anybody gets fantastically airdropped at a crossroad. One arrives at a crossroad by following a certain path. A person stuck at cross road is likely to benefit a lot by contemplating on the path taken, perhaps give a thought to the journey so far.

For the journey back to Srinagar from Leh, taking the path from Zoji La Pass down to Baltal, on the top of a glacier, blind-folded, he found himself wrapped in namdas and buffallo hide, stuffed alongside him were his sturdy mountain guides, the racepahs. This most arduous part of the journey commenced with Bismillah ir-Rahman ir-Rahim and a gentle push down the vast ice sheet. This journey was over 40 minutes or an hour later, he survived.

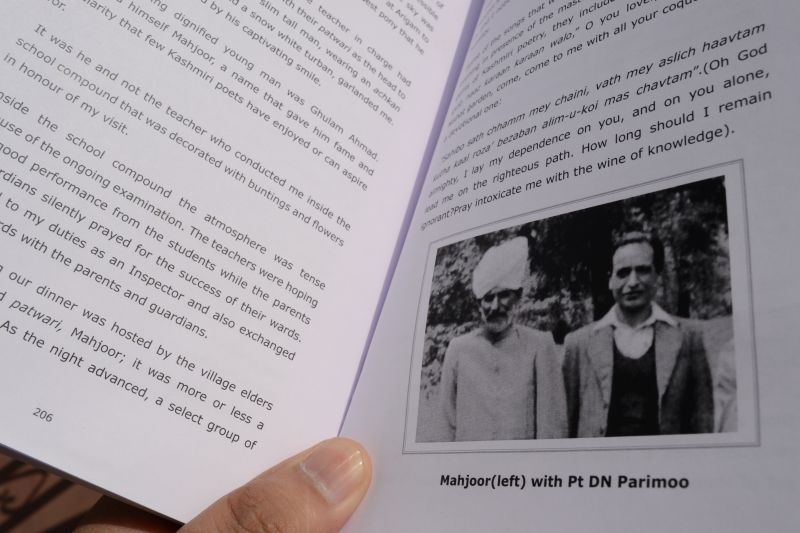

The year was 1935 and D.N Parimoo was 24. In 1996, while living miles away from Kashmir, in a diary he started writing about his journeys and experiences in Kashmir. His work as an educationist offered lot of travel and an opportunity to intimately know some of the major mover and shakers of Kashmir. In 2000, his son P.Parimoo compiled these writing into fine a book, ‘Kashmiriyat at cross roads; the search for a destiny’.

Till now I had only read a bunch of travel account of westerners in Kashmir. In most of these accounts, by 1930s, Kashmir comes across as the land of great retreat for the western man (and it must be said, western women), the land of idyllic beauty and its poor haunted natives. In these accounts, all that was to be discovered in Kashmir, had been discovered, all the beauty spots, had been found and marked, all the activities that could be done in Kashmir, had been listed, all accounted. There account would often tell you something like – you must experience the thrill of rowing down Jhelum, hire a dozen boat people from one of the city bridges, the boats are quite comfortable and now designed for your comfort, you could cover the entire city in a couple of hours. As a child D.N Parimoo recalls often waving at western tourists rowing down Jhelum, inexplicably to him, always in a hurry. His own boat journeys on Jhelum, often lasted for days, but days filled with singing and music, stories and extended families. In his later years, he came to associate ‘Power Show’ with white-man’s violent rowing exercises on the river.

This is the first time I got to read the travel accounts of a Kasmiri traveling in Kashmir back in 1930s. And its a simple yet graphic account of what must have been truly exhilarating journeys. Best of these is the one undertaken by D.N Parimoo to Leh at the age of 22, already married. There is thrill and excitement experienced by a young man, there is also the shrillness, fear, madness, ghosts, wav-jins offered by barren, lonely but beautiful land. And the destination of this journey, Ladakh or Little Tibet as it was often called back then, a place that came under the state of Jammu and Kashmir after its conquest by the Dogra General Zorawar Singh in 1834, comes across as a place seeped in eastern-eastern mysticism, and surprisingly a place offering lots of easy bohemian sex, lots of Chaang and Araq – the local booze.

This book offers all kinds of information: sanitary habits of Kashmiri Pandits and Kashmiri Muslims, use of yender or needle of spinning wheel for aborting babies. And it offers surprises: ‘tantrics‘ at Bharav Temple of Maisuma, students of Sheikh Abdullah tauting him with the name ‘Gada Kala’ or Fish Head.

One of the most incredible accounts in this book is also about a journey, but a journey of another kind. It is the account of how old Pandit orthodoxy breeding, surviving, opposing new waves of change, new thoughts, trying to strike big time, under the command of AN Kak and his Dharam Sabha was dealt the death blow by few emancipated young men of Yuvak Sabha of Pt Prem Nath Bazaz. It was a coup. The young men actually caught the old men by their beard and told them to shut their trap. The story of Bazaz, a man inspired by writings of Marxist thinker M N Roy, is in itself symbolic as he was sentenced to exile by Pandit community for endorsing Glancy Commission Report about incidents of year 1931. Bazaz returned and went on to play a critical part in the birth of media in Kashmir (a story well documented in this book).

My only problem with the book is references to ‘Jews and Kashmiris’. I find these allusions quite distracting, and a big magnet for kind of social theorists. But mercifully the book only mentions is fleetingly and given the time when this book was originally written, mid-90s, just when certain Jewish-Joo stories first started doing rounds, it is an understandable interest. Also one has to consider the fact that western audience might find these stories equally interesting. Another mercy is that even though the title (which could have been shorter) may give you certain ideas, there is hardly any politics in this book. (Aren’t emails that nice Kashmiris good heartedly send each other a reason enough to give one a bad case of ‘nahi-nahi-aur-nahi-mainay-wyun-bahut-sara-politics-khaya-hai-be-chus-full.‘? )

At one elementary level, the story of Kashmir is about people trying to retrace the old paths, hoping to find that one perfect milestone with the inscription ‘Paradise’, a paradise free of crossroads. Young re-tracing and remetalling the old conservative roadways laid by travelers who too were once young. Broadening them. Reclaiming. Selectively. Destroying remains of the paths taken less often taken.

“Everywhere in life there are crossroads. Every human being at some time, at the beginning, stands at the crossroads – this is his perfection and not his merit. Where he stands at the end (at the end it is not possible to stand at the crossroads) is his choice and his responsibility.”

~’The cares of the Pagans’ from Søren Kierkegaard’s Christian Discourses

-0-

I am thankful to P.Parimoo ji for sending me a copy. Those interested in this interesting book:

-0-

In 1952 Dina Nath Nadim on a visit to Peking gets to see Chinese classical opera, White Haired Girl. He is impressed with the format and believes that it could very well work for a Kashmiri story with Kashmiri folk music. 1953, only a year later, drawing inspiration from a popular Kashmiri legend about change of seasons, he comes up with Bombur ta Yambarzal (The Narcissus and the Bumble Bee). That year this opera is staged for the first time at famous Nedou’s Hotel. Acclaimed to be first of its kind in the entire country, it proves to be a roaring success among the public who can’t keep themselves from singing the songs from this original production. Quasi propagandist context mixed with genuine folk music, a popular story that everyone knows, earnest socialist fervor triggered by promise of a new political change, another new beginning – this creation of Nadim, not yet disillusioned, offers it all. It is a significant achievement.

An achievement significant enough to draw a special audience. In 1955 the show, that has already had a few re-runs, is again put up at Nedou’s Hotel for special guest – military leader and Marshal of the Soviet Union Nikolai Bulganin who is accompanied by First Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party’s Central Committee Nikita Khrushchev. At the end of the show, the two political giants offer Nadim a hug each. The story was believed to be allegory on American Capitalism and Soviet Socialism.

That was the story of ‘Bombur ta Yambarzal’ this far.

Nadim was joyous that day.

|

| Dina Nath Nadim, the artist, between the two colossus Khrushchev and Bulganin. 1955. Found this rare photograph (by Anatoliy Garanin) at RIA Novosti website. Dina Nath Nadim stood unidentified, unmarked, with his crew. [Came across this photograph thanks to Autar Mota ji] |

|

| Update: July 7 2013. Another photograph of the event. Via: Photodivison India [Update: July 29,2013 Details about the performers in the photograph sent in bt readers] |

This great interest of Russians in a Kashmiri story wasn’t sudden. It was cultivated. In 1955, on a diplomatic goodwill mission for USSR to Kashmir, Uzbek communist leader Sharaf Rashidov, a name that in later years would be called ‘a communist despot’ and a few years later would be called ‘a true Uzbek hero’, came across Dina Nath Nadim’s modern re-telling of an inspiring old Kashmiri story. By the end of 1956 Rashidov was already out with his interpretation of the story in a novella titled ‘Kashmir Qoshighi’ ( also known as Song of Kashmir/Kashmir Song/Kashmirskaya song) acknowledging Nadim’s work.

-0-

Much dwelling, much seeing, much tasted from pleasure and burning the teacher has asked the schoolboys,whose young eyes were alert, and mind just spriad it’s wings for a long-distance flight:

– Where the wisdom of people originates?

– In experience, – one has answered.

– In thought, – another has answered.

– In connection of experience and thought, – third has answered.

And again, having thought, the teacher told:

– The experience of the man dies together with the man, the mind of the man dies together with the man. For the tam of ours is short! The wisdom of the people originates in memory of the people. It is – ocean, from which the mining flows and springs becoming on the way the rivers are born. Memory is the consequent of wisdom and it is the reason of it. But where the memory lives and what gives it force to pass, enriched, from century to century, from past times to times of future?

It is a figure on a wall and a picture on a canvas.

It is a line on an stone and book.

It is a fairy tale, tradition and legend.

It is a song and music.

In them memory of people, which widening the beaches, flows from breed to breed, in them is wisdom of people, which as all the inflaming plume, is transmitted from breed to breed

~ lines from Rashidov’s Song of Kashmir (via this interesting Russian article)

-0-

By the start of 1960, the dream was already over for Nadim and many of his friends. The poets were coming to term with new realities, promises broken and perhaps their own role in the events of past. Making a departure from his earlier ‘progressive’ style, in his 1959 poem Gassa Tul (Blade of Grass) Nadim wrote*:

This blade of grass

Like me

Soft silk when sap was there

Bowed to the sun and waved with the wind.

In winter nights its roots were lost.

Robbed of its sap, it stood erect,

Dried up, stiffened with false pride,

Changed in kind, having outlived its day.

Blow on it, it crumbles;

Step on it, it is dust;

Show it a flame and

Ashes is all.

-0-

1965 was the year of second Kashmir war between India and Pakistan. It was also the year when USSR’s famous Soyuzmultfilm studio produced an animated film called Наргис. Soyuzmultfilm excelled at producing animated fairy tales and other popular stories targeted at children, but for Наргис the story came from Rashidov’s Song of Kashmir. Interesting the film retained the original Kashmiri names of all the characters sketched originally by Dina Nath Nadim, all the names except Yambarzal who is given the popular name Nargis, the name of this film.

|

| Nargis |

|

| Bombur |

|

| Wav |

|

| Harud |

With the birth of Doordarshan, by mid-1970s, animated films from Russia made appearance on Indian television science, they would keep up such appearances for decades to come even after the fall of USSR and Soyuzmultfilm getting devoured in capitalist market.

In his early 1970s poem Hisaab Fahmee (Know the Science of Number) about a man whose account balance has gone haywire, Nadim laments*:

It never became four,

At last I saw only a cypher,

One round zero,

Now shrinking, now swelling again,

Like breathing in and out.

-0-

* translated by T.N. Raina

“Yusuf left Kashmir, and on January 2, 1580, appeared before Akbar at Fathpur-Sikri, and sought his aid. In August he left the court armed with an order directing the imperial officers in the Punjab to assist him in regaining his throne. His allies were preparing to take the field when many of the leading nobles of Kashmir,dreading an invasion by an imperial army, sent him a message promising to restore him to his throne if he would return alone.

He entered Kashmir and was met at Baramgalla by his supporters. Lohar Chakk was still able to place an army in the field and sent it to Baramgalla, but Yusuf, evading it, advanced by another road on Sopur, where he met Lohar Chakk and, on November 8, 1 580, defeated and captured him, and regained his throne.

The remainder of the reign produced the usual crop of rebellions, but none so serious as those which had already been suppressed. His chief anxiety, henceforth, was the emperor. He was indebted to him for no material help, but he would not have regained his throne so easily, and might not have regained it at all, had it not been known that Akbar was prepared to aid him. The historians of the imperial court represent him, after his restoration, as Akbar ‘s governor of Kashmir, invariably describing him as Yusuf Khan, and he doubtless made, as a suppliant, many promises of which no trustworthy record exists. His view was that as he had regained his throne without the aid of foreign troops he was still an independent sovereign, but he knew that this was not the view held at the imperial court, where he was expected to do homage in person for his kingdom. In 1581 Akbar, then halting at Jalalabad on his return from Kabul, sent Mir Tahir and Salih Divana as envoys to Kashmir, but Yusuf, after receiving the mission with extravagant respect, sent to court his son Haidar, who returned after a year. His failure to appear in person was still the subject of remark and in 1584 he sent his elder son, Ya’qub, to represent him. Ya’qub reported that Akbar intended to visit Kashmir, and Yusuf prepared, in fear and trembling, to receive him, but the visit was postponed, and he was called upon to receive nobody more important than two new envoys, Hakim ‘All Gllani and Baha-ud-din.

Ya’qub, believing his life to be in danger, fled from the imperial camp at Lahore, and Yusuf would have gone in person to do homage to Akbar, had he not been dissuaded by his nobles. He was treated as a recalcitrant vassal, and an army under raja Bhagwan Das invaded Kashmir. Yusuf held the passes against the invaders, and the raja, dreading a winter campaign in the hills and believing that formal submission would still satisfy his master, made peace on Yusuf’s undertaking to appear at court. The promise was fulfilled on April 7, 1586, but Akbar refused to ratify the treaty which Bhagwan Das had made, and broke faith with Yusuf by detaining him as a prisoner. The raja, sensitive on a point of honour, committed suicide.

Ya’qub remained in Kashmir, and though imperial officers were sent to assume charge of the administration of the province, attempted to maintain himself as regent, or rather as king, and carried on a guerrilla warfare for more than two years, but was finally induced to submit and appeared before Akbar, when he visited Kashmir, on August 8, 1589.

Akbar’ s treatment of Yusuf is one of the chief blots on his character. After a year’s captivity the prisoner was released and received a fief in Bihar and the command of five hundred horse. The emperor is credited with the intention of promoting him, but he never rose above this humble rank, in which he was actively employed under Man Singh in 1592 in Bengal, Orissa, and Chota Nagpur.”

~ The Cambridge History of India:Turks and Afghans Volume 3 by Sir Wolseley Haig (1928).

-0-

It is as story as it is not often told, for example the last of Bhagwan Das never made it to popular telling of the story.

Image: Collage based on K. Asif’s Mughal-e-Azam – a work essentially (derived form popular lore) about Akbar’s conduct and how he went about the business of running an empire and of course how this business ruins love. The popular Kashmiri story of Yusuf and Habba Khatun finds some parallels in that story. If one considers the ending of the film Mughal-e-Azam – Akbar providing a safe passage, an anonymous escape and a popular death, to Anarkali and if one considers the alternate (unpopular) ending of Yusuf Chak and Habba Khatun story – graves of the two lovers side by side at a desolate place in Biswak village in Nalanda, Bihar and not the version that sees Habba Khatun pinning for her lost King’s love till the last of her breath, the parallels, rather inversions, are unsettling. In popular memories, love stories with happy ending are no love stories at all.

-0-

“The pamphlet cover displayed above is from a title published in 1948 by the Kashmir Bureau of Information in Delhi. The design is arresting, and clearly leftist in inspiration. The designer (the name is in the bottom left hand corner) was Sobha Singh, at the time a young progressive artist. In later years, he became better known for his religious paintings of the Sikh Gurus.

The woman in the foreground depicted lying on the ground and aiming a rifle is Zuni Gujjari, a woman from a milkman’s family who became renowned as a militant supporter of the National Conference, the main Kashmiri nationalist party. The black and white photograph is of members of the Women’s Self Defence Corps, a women’s militia set uplargely by Communist supporters of the National Conference in October-November 1947, when Srinagar was in danger of being overrun by an army of Pakistani tribesmen.”

Found it at the site of Andrew Whitehead author of A Mission in Kashmir.

Besides Zuni Gujjari, the other women featured in this incredible image include Krishna Misri (nee Zardoo), her younger sister, Indu, Begum Zainab, Jai Kishori Bhan. Usha Kashyap – known now as Usha Khanna– wife of Indian freedom fighter Rajbans Khanna (associate of Director Bimal Roy) , niece of Balraj Sahni (one of the pioneers of left leaning IPTA or Indian People’s Theatre Association and the hero of 1972 bilingual film Shayar-e-Kashmir Mahjoor based on life of Kashmiri poet Mahjoor) and the founder of Samovar restaurant at the Jehangir art gallery in Mumbai.

Do check out Andrew Whitehead’s blog for more on these incredible women and stuff like this:

-0-

Tip off- Autar Mota ji. Thanks!

-0-

Update: Got the name of one more woman (not in Andrew Whitehead’s article) in that pamphlet thanks to Vijay Kashkari Ji. He writes:

“My mother Shanta Kashkari is also in photograph. She was an active member of the peace brigade formed for voluntary works, when Kashmir was raided by the raiders.My mother is 2nd behind Jai Kishori Ji [woman under first ‘E’ of DEFENDS]. She is wearing white saree, head and arm is covered by the saree.”

Shanta Kashkari would be the woman under left edge of ‘D’ of DEFENDS.

-0-

|

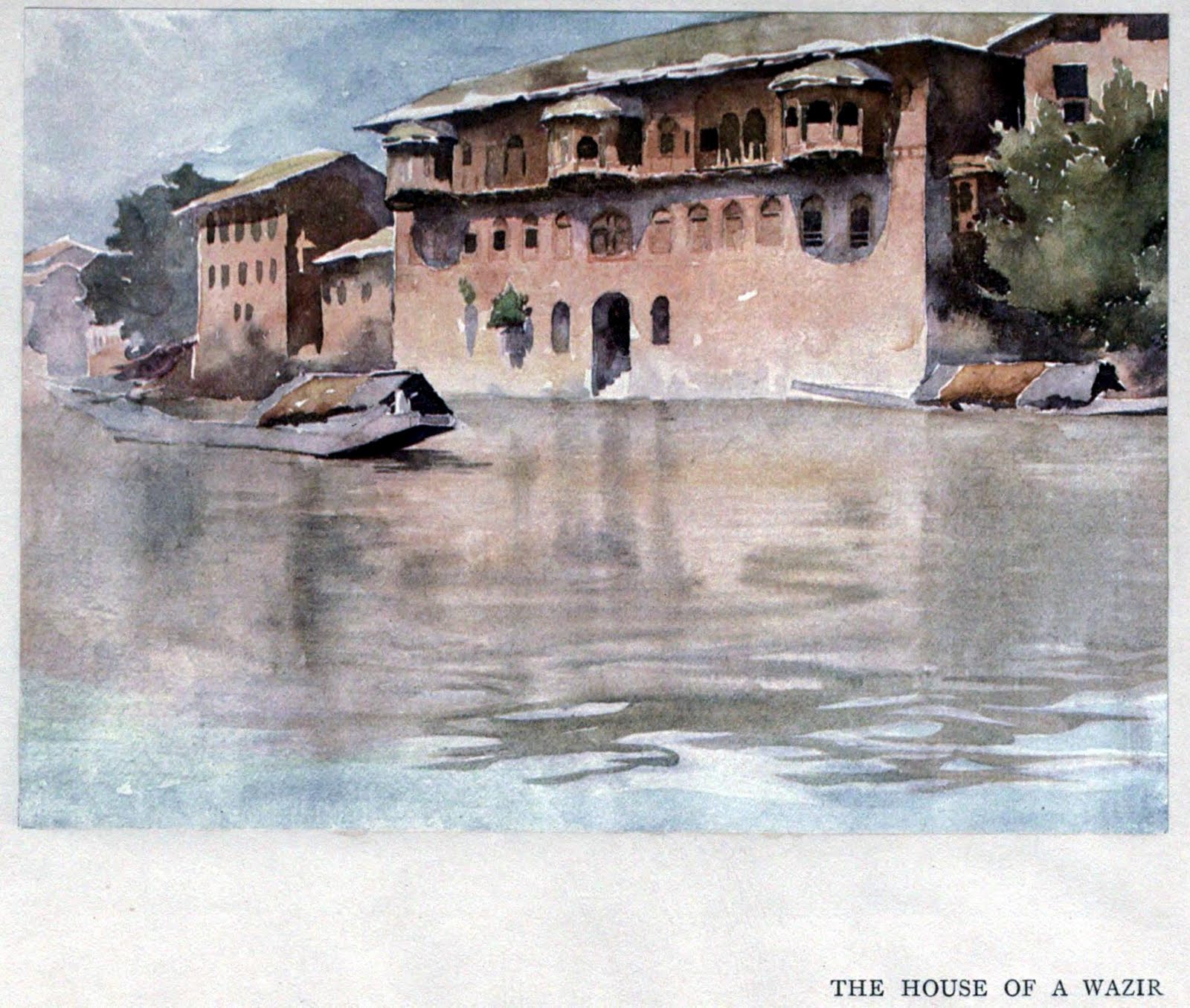

| From the looks of that towel left for drying on the window sill, somebody actually lives in that house. Update: The place is known as Aabi Guzar. Apparently at this place people used to pay taxes for using the water ways. 2010. |

Update:

Notice the design.

Drawn by H.R. Pirie for P. Pirie’s ‘Kashmir; the land of streams and solitudes’ (1908).