The film starts with a man welcoming a recently orphaned young son of his sister into his family. The man’s young daughter takes a special liking for the orphan boy. The plot is set for a childhood romance that will blossom in youth. The local bad boy of the village with perhaps a linking for the girl grows an instant dislike for the boy. How the world conspires against them and how their love survives, that in a nutshell is the premise of the film

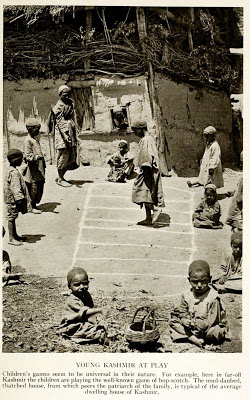

On the surface of it, there isn’t anything new to this story written by Ali Mohammed Lone, a man with literary background. It is plot of countless Hindi films. But it is the social background, the Kashmiri culture, within which this simple story is told, its music, the idioms of its language and the gesticulation of its people, that all add various unique delicious layers to the experience of watching this story unfold on screen. Even to a Kashmiri viewer it offers layers of ecstatic wonder, layers that the interested viewer can devour to his contentment in each viewing.

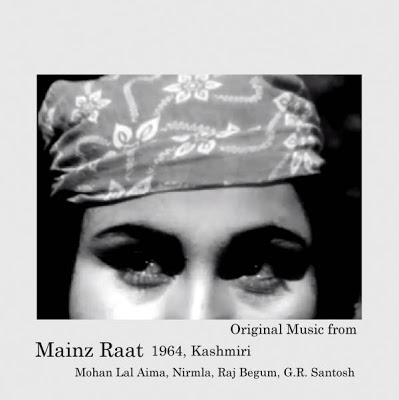

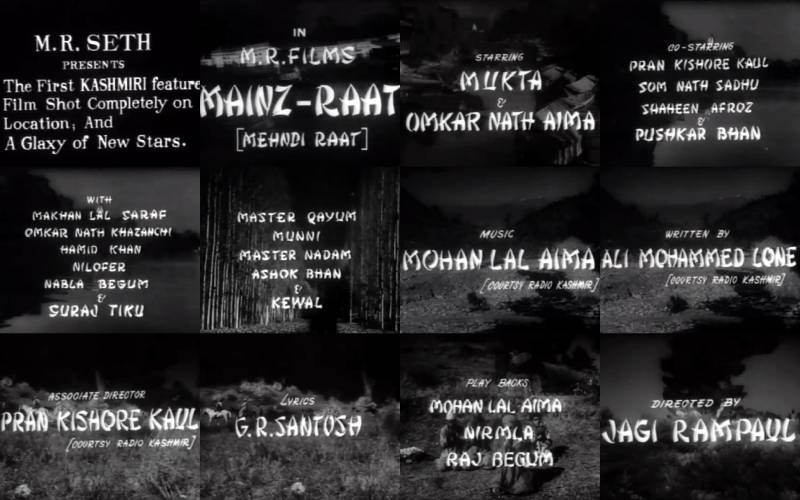

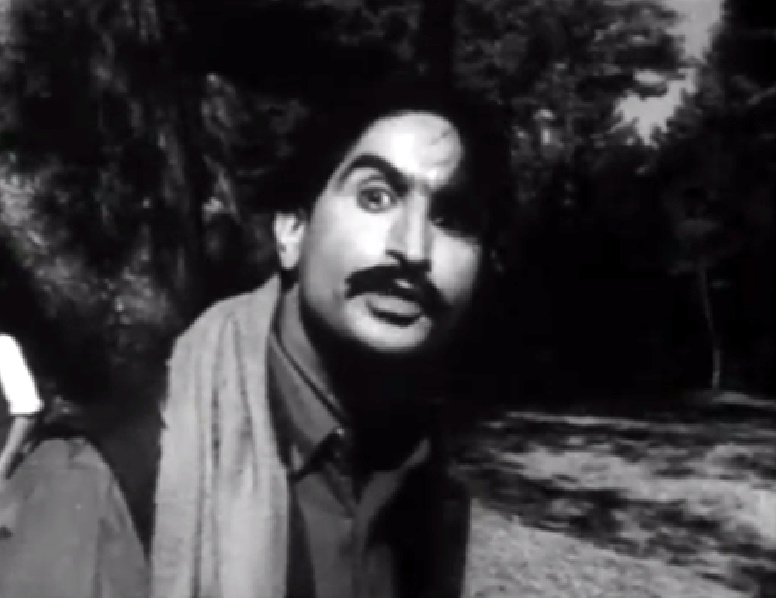

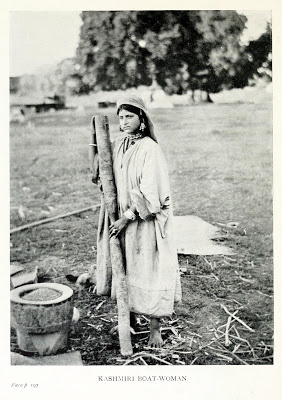

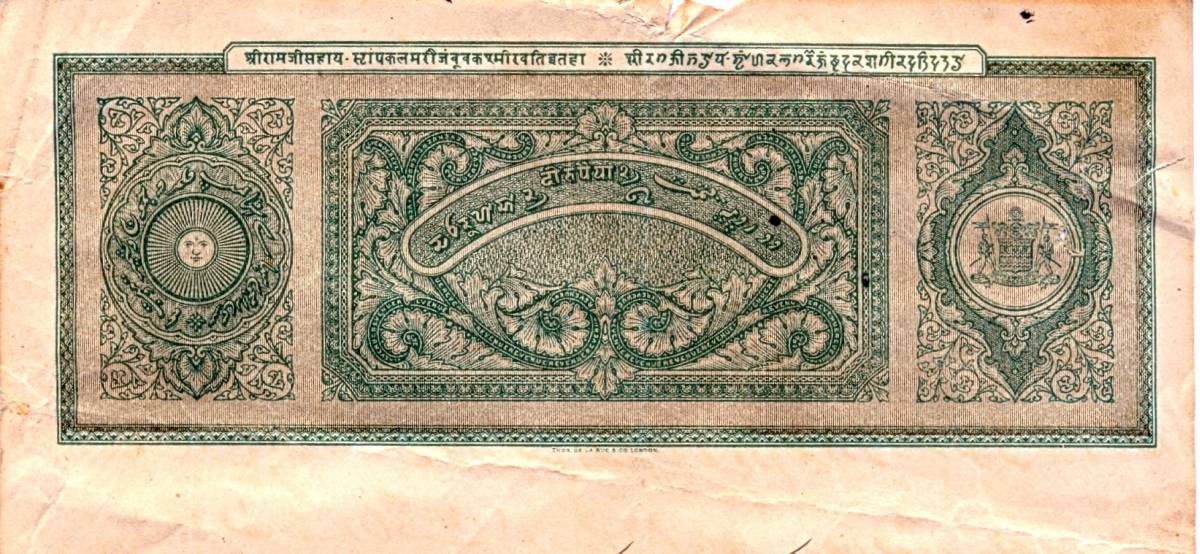

Although nothing much is known about the film’s Director, Jagi Rampaul and the Producer, M.R. Seth, this film was considered path breaking enough back in 1964 to win a President’s Silver Medal. Generations of Kashmiri people remember this film for some great performances by lead cast: Omkar Nath Aima as hero Sulla.Sultan, Mukta as heroine Sarye/Sara, and an outstanding act by Pushkar Bhan as villian Barkat. But most of all this film was remembered for its use of folk songs and some beautiful new Kashmiri songs written by famous poet-writer-painter artist G.T.Santosh and set to music by great Mohan Lal Aima. For generations this film has been known as the first Kashmiri film ever made.

What now follows is not a review of the film, it’s something else, it’s how the film interact with memories.

The opening scene of the film when Rajab arrives in the village to check up on Sultan.

Rajab, known fondly as Rajab Kaka or Rajab Uncle, distributing sweets, maybe Shirin or Nabad, sugar candies, to children of the village.

After burying Sultan’s mother, Rajab Kaka takes Sultan alongwith him back to his village. As they start of, a woman hands him Kulache for the journey and beseeches him to take care for the motherless child.

Sara, the daughter of Rajak and Sultan hit it off instantly. Meanwhile…

Sara’s brother Razak is chilling out with Barkat the bad boy. Barkat spots the Pandit boy, Poshkar walking with a stack of hay on his back. Just for fun, Barkat flings his cigarette bud onto the load on Poshkar. As Poshkar slowly and without knowing carries a blaze on his back, the bad boys laugh out at the scene.

Sultan and Sara reach the spot, Poshkar gets rescued by Sultan. With this episode Sultan makes a friend, the Pandit boy Poshkar.

|

| ‘Myane Bhagwano’, O my God. Poskar’s cry on realizing that his stack was on fire. |

The boy and the girl grow up, already deeply in love.

|

| ‘Batt’e Aaprawun’. Sara feeds Sultan. |

Barkat fumes.

Sara and Sultan will marry each other, is an eventuality even hinted by old Rajab Kaka.

|

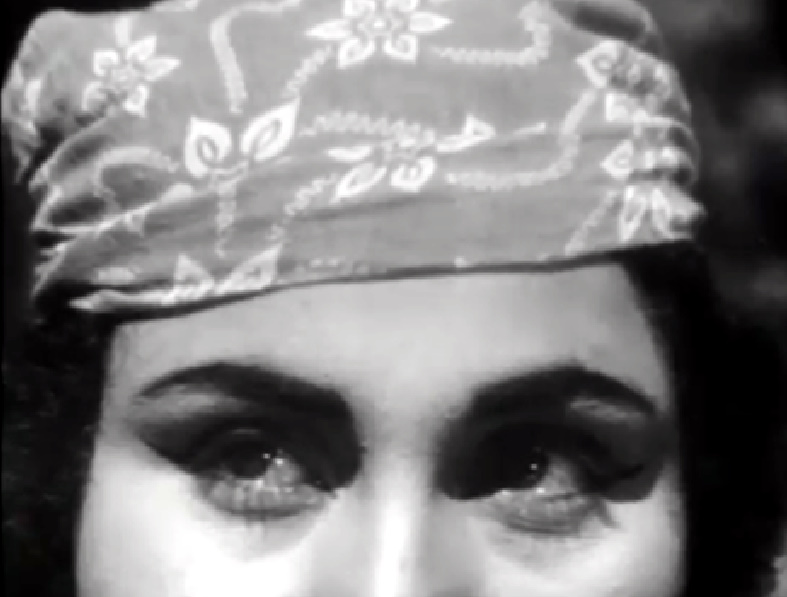

| Notice the headgear on the woman who walks into Poshkar’s shop to barter an egg |

The only comic sequence involves a woman who walks into Poshkar Nath’s shop to barter an egg. In a demonstration of typical Kashmiri humour, Poshkar Nath quip’s about the size of the egg.

After the joke, the stage gets set for the gloom to descend. Barkat starts poisoning Razak’s ears, how the village people are not saying nice things about Sara and Sultan. Razak, in a round around way tries to reign in his sister, but Sara snubs him. Razak goes to his father complaining about relation of Sara and Sultan. Razak seems more worried about the fact that Sultan can stake a claim on what he believes to be his property and land. Rajab Kaka tries to put some sense into his son, but the worms of doubt get laid into his mind too. After a villager also asks him about Sara and Sultan, the father feeling ashamed, publicly lashes out at Sara.

Now Barkat plays he next move. Using his minions, he takes the matter to village panchayat with the purpose of throwing Sultan out to village.

As the minions start to take control of the panchayat’s proceedings, Pandit Poshkar Nath moves in to defend the case in favor of his friend Sultan.

The matter ends with Poshkar Nath not only stopping Sultan’s excommunication but using his wit even manage to get a ruling that Sultan has a right to the property.

Barkat isn’t very happy with this outcome. The object of his immediate anger is Poshkar.

Barkat plans to destroy Poshkar by looting the supplies coming in from city for Poshkar’s shop. As the plan is being executed, Sultan comes in at the last moment and fights off the looters.

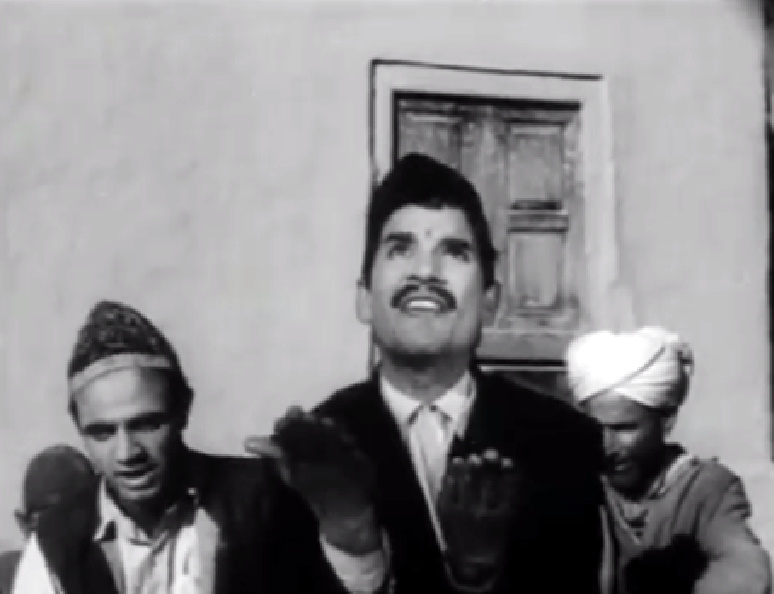

|

‘Kal’e Thol’ – Sultan’s Kashmri Headbutt.

The only other genuine Kashmiri combat move involves throwing a Kangri over the opponent’s head.

I have actually seen my father perform this artistic maneuver many moon ago. |

After this the forces that try to seperate Saran and Sultan only get stronger. Sara sees a storm coming. She shares her worries with her friend, the wife of Poshkar. [There voices drowned in the gurgling of the stream.]

Meanwhile, Poshkar Nath tries to talk sense into Rajab Kaka who now seems to be dying of guilt. Rajab Kaka admits that he still loves Sultan like his own son but it’s the voice of the villagers that he fears.

The lovers grow sadder. Razak sings his love’s lament. Rajab Kaka dies. Razak get’s into mounting debt due to his gambling habit. Barkat makes his next move. Sara knows what is coming her way.

She talks to her friend about the fate that has befell her.

She asks God for help.

The village bard sings. The visuals get poetic.

Sara gets buried under autumn leaves of Chinar. Harud, autumn is upon the village and upon Sara. Play of seasons is constant theme in modern Kashmiri literature. This scene pays dues to that theme.

Razak finally gives in and to settle his debts, agrees to marry-off his sister Sara to Barkat.

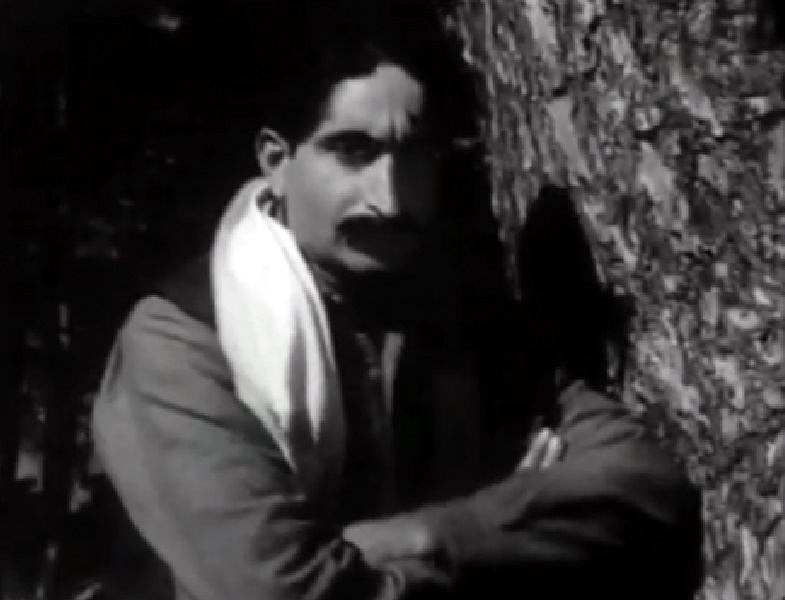

Sara’s Mainz Raat arrives. Before the night, she meets Sultan one last time. Sultan bemoans his fate, swears over his love and respect for Rajab Kaka. Sultan bemoans his orphan status.

He tells her he is happy for her. He tells her maybe it wasn’t meant to be. He asks Sara why isn’t there Henna, Mainz , on her hand.

The film gets its title from this sequence. It’s the most significant scene of the film.Sara’s Mainz raat is symbolically arranged by her lover Sultan when he puts bangles around her arms and wishes her happiness.

Sara is married off over the sound of Kashmiri wedding song. [At this moment my mother walks into the room, without asking what I was upto, goes through my cloths singing the song from the film. A song about Mainz.]

The brilliance of Mohan Lal Aima’s use of music shines through. He was at his peak back then. Even the use of background score for someone the scenes is well ahead of time and imaginative. And the music is just not limited to folk, there’s contemporary film, with a distinct Indian Cinema touch of the ear and there is classical Indian music setup. [I will be posting a Soundtrack from the film sometime soon. A cleaned up sound extracts from this film]

Sultan looks on.

Barkat get a wife. He is infuriated at seeing those bangles around Sara’s wrist.

He knows he has caged a bird.

Now, having again lost all his possessions, Razak realizes his follies. He is repentant.

We now see a new side of Sara’s personality. There is residence. She fights with her husband over the state of his brother. She wants Barkat to help Razak out. Barkat too notices this side of Sara’s personality. He who used to flick knives is now beaten by the verbal lashing of his wife.

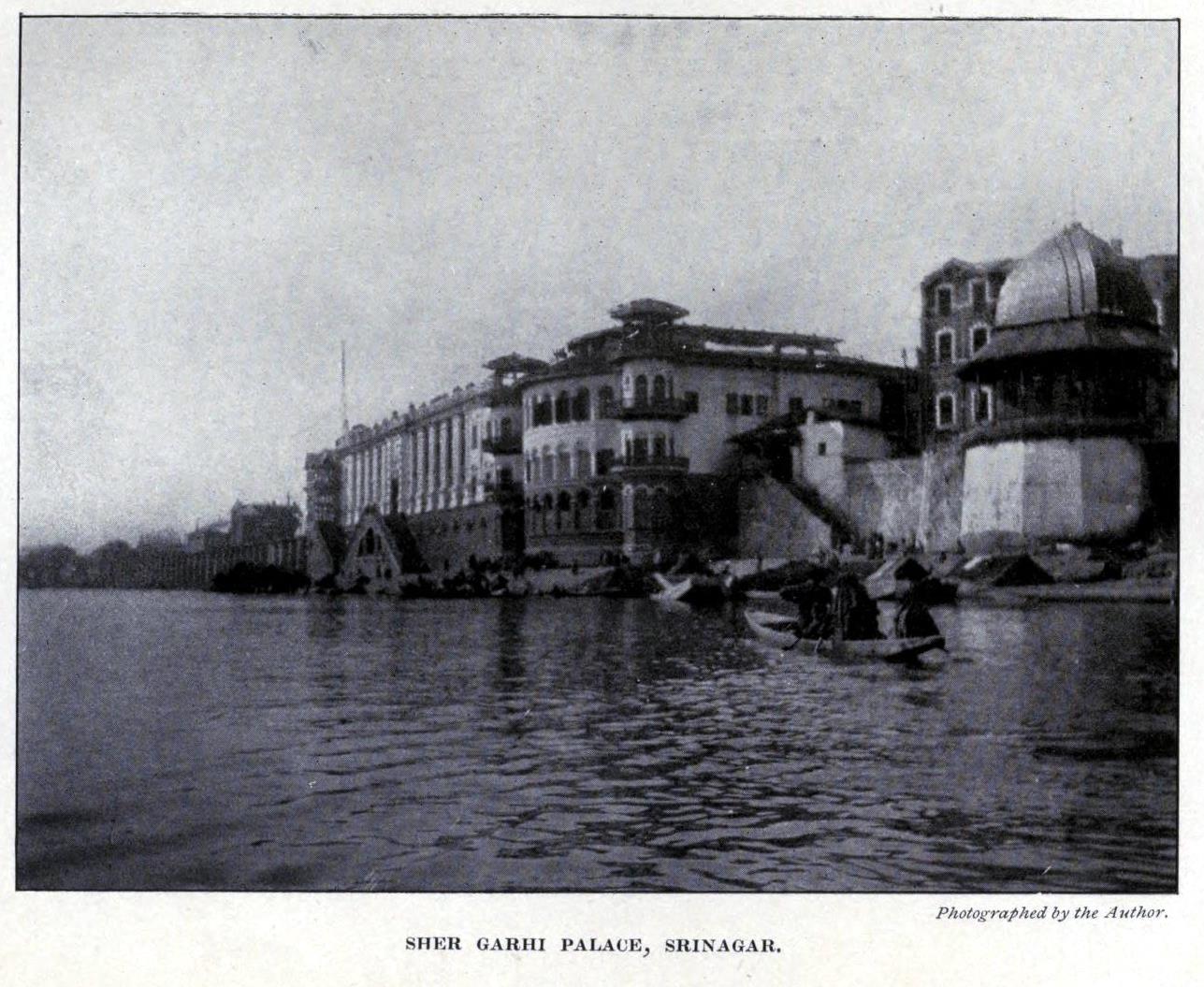

He gets a quasi heart-attack. We now see a new side of Barkat’s personality too. Strong, evil Barkat now comes across a weakling afflicted by consequences of nature. He, the corrupter of simple village folk now sees cure, refuge in city, the capital of corruption. It’s a textbook Indian film situation but to see Srinagar at the seat of corrupt requires a present Kashmiri viewer to really challenge his senses.

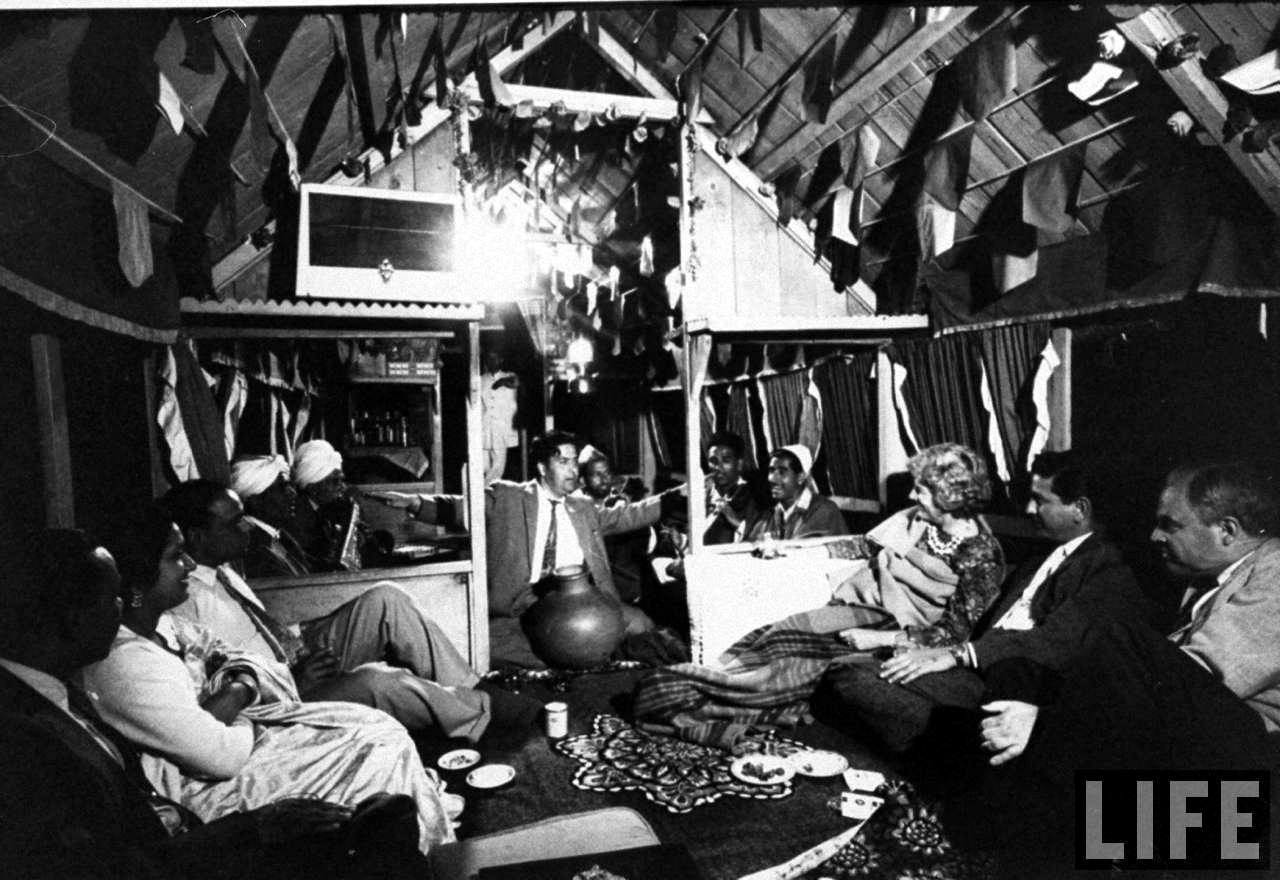

Srinagar is the waterdown version of big bad Bombay in this social setup.

Barkat acts like an a Kashmiri version of Devdas. He wants to drink as much alcohol as there is water in the ocean. Definitive Devdas inspiration. He smokes, drinks and gambles. Back then when Srinagar wasn’t yet cleansed, among other things Srinagar still had vice centers like gambling den, drinking joints and cinema hall. Now these are only private pleasures in the city.

Sara now shows another facet of her personality. She now weeps for her husband.

Over the grave of her father, she cries for husband and wishes his return. Her two brothers, Razak and the Pandit brother Poshkar Nath console her.

Now, Sara, the woman who used to tie threads on Pir’s mazaar for fulfillment of her love, grabs a black veil and prays to Mustafa, the head of all Pirs.

The beauty of it is that this transitions is presented so logically that it takes imagination to conjure up conflicting natures of her personality.

She is delighted when Sultan volunteers to find and bring back Barkat from the city.

Sultan grabs Barkat from a den and brings him to Sara.

Barkat is dying. He is repentant. He wants the bird be set free.

Barkat dies.

Earlier in the movie on being asked by Poashar Nath about getting Sara married, Rajak Kaka had said that by the end of Harud, autumn, Sara will be happily married off.

The season has changed. Harud is over. We hears the songs of reaping.

We see Sara and Sultan together working the field, reaping. We see a new sun rising.

-0-

I first watched this film on Doordarshan in its afternoon regional film telecast on some weekend more than a decade and a half ago when I was still a teenager. I must admit I didn’t grasp most of it back then but it felt significant back then as some of the sights and sounds from the film remained with me for a long time.

A couple of years back, when Kashmir again started churning inside my head, I remembered this film. Given the state of film archives in India, I never thought I would be able to watch it again. I felt the loss of this film.

The complete film, probably procured from Pune film archives (which for some unknown reasons does not list it in its online listing) is now available on Youtube channel of Rajshri. For some strange reason a quick google search on this film will have you believe that the film was made in 1977. Which of course is wrong. It was made in 1964. And for obvious, self-defeating financial reasons the channel uploader had tagged this film with all kind of nasty, profane keywords (hence the pathetic related videos over there). Which of course is wrong. But at least we now have the film, even if it now swims in a river of innoquitues that is Internet.

-0-

I cannot by help think that if this film was to be re-made now, it will be pregnant with elaborate political connotations and undercurrents. It will be something flashy and sense numbing, something that will try to educate you but won’t let you think, something that will try to interpret ideas but won’t dare you to interpret. It will be real. It won’t be cinema. It won’t be something as simple as Mainz Raat of 1964, the first Kashmiri film.

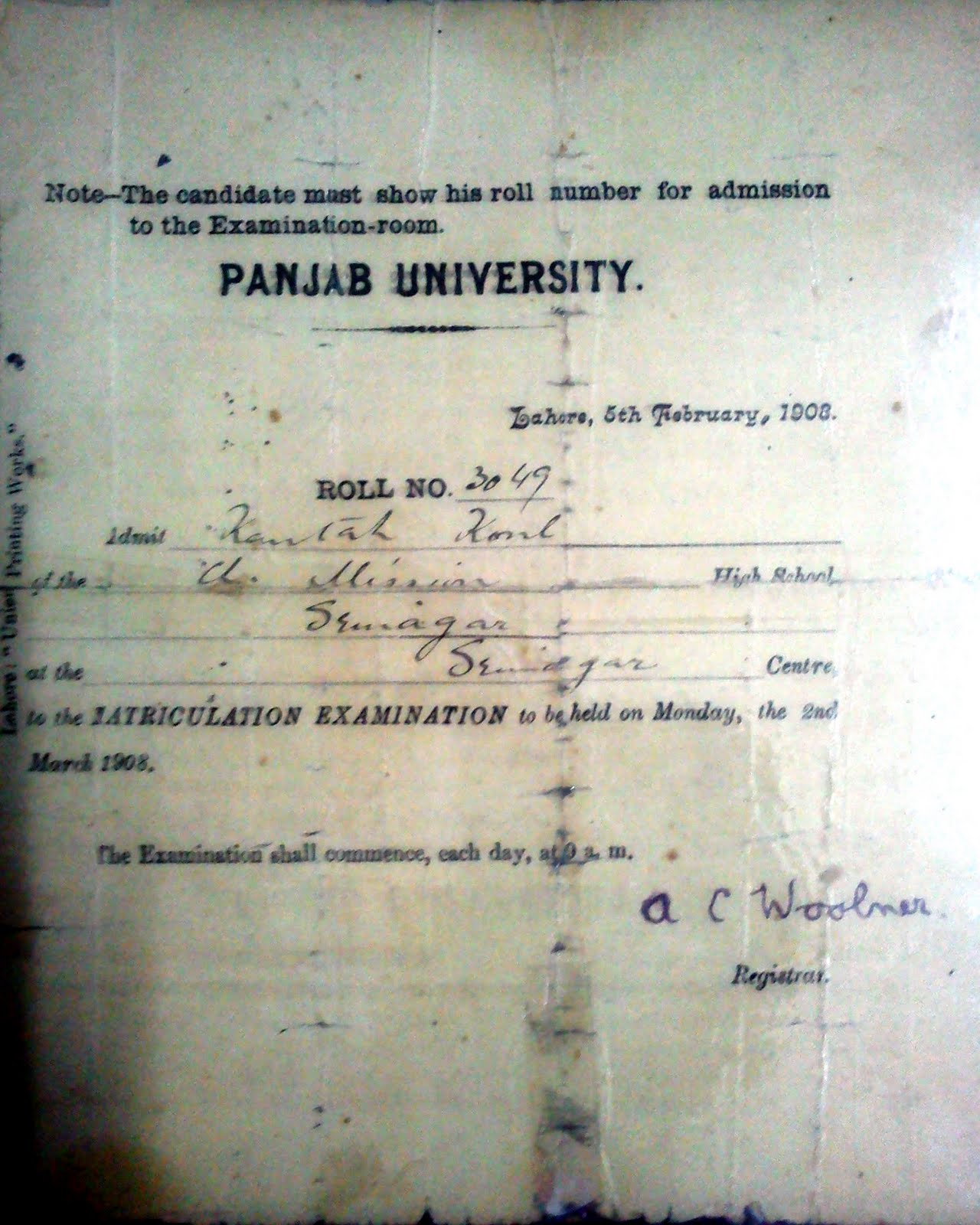

“The first film Maanziraat was released in 1968. It was directed by Pran Kishore, featuring Omkar Aima as the hero and Krishna Wali as the heroine, with Som Nath Sadhu, Pushkar Bhan and others as the supporting cast”

~ Came across this interesting bit in ‘A History of Kashmiri Literature’ by Trilokinath Raina. In the original credits Pran Kishore Kaul is mentioned as Assistant Director. Also the lead actress is named as ‘Mukta’. But from what I have heard, the actress as almost certainly Krishna Wali. Pandit community is so small that I have actually heard about the tough days that the woman had to face in her real life.