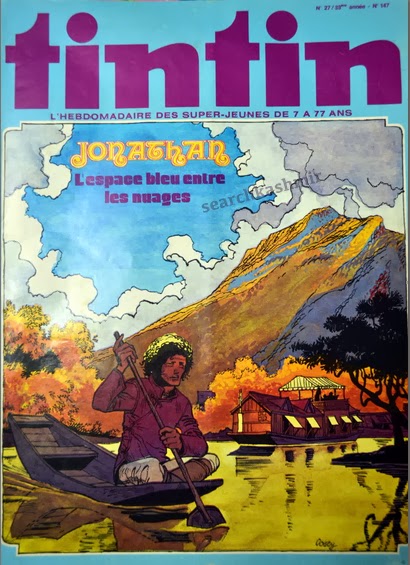

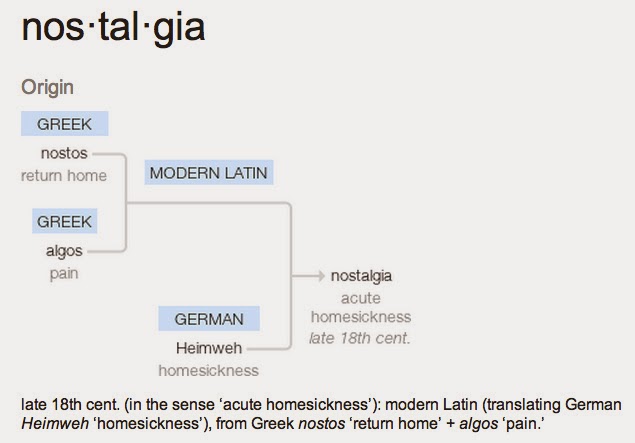

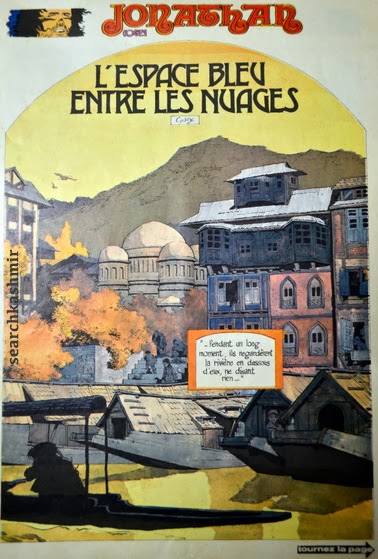

Kashmir in Jonathan series ‘L’espace bleu entre les nuages‘ (The blue space between the clouds) by swiss artist Cosey (Bernard Cosandey) for Tintin Magazine No.147, July 4, 1978.

The plot revolves around sale of rare European paintings meant to fund a militant movement run from Srinagar. The movement in this case happens to be a veiled reference to ‘Free Tibet’ movement whose main agents have taken refuge in Kashmir.

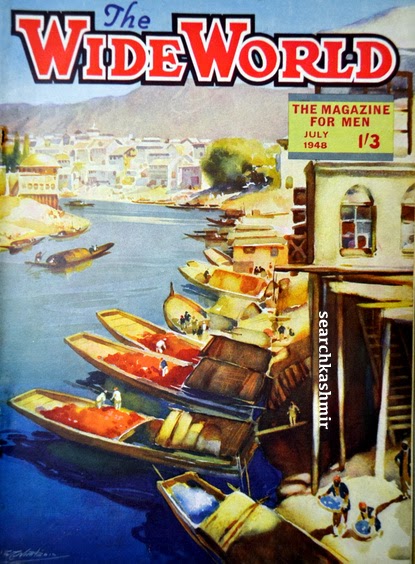

Much like the old European travellogues, Srinagar here is presented as the springboard to the roof of the world. The comic comes from a time when comics were art, this collection apparently is supposed to be read with the background score of Beethoven (Concerto No. 3 in C minor op. 37) and Chopin (Concerto No. 2 in F minor op. 21).

To get the art and feel of the place right, Cosey actually travelled to Kashmir and seems to have soaked it all in quite well. The issue also carried a brief piece by Cosey about his experience in Kashmir (along with some photographs by Paquita Cosandey, who usually did script and design for him).

Tintin Magazine was meant to be a space where new and future comic works by various artists could be showcased. ‘L’espace bleu entre les nuages’ as a complete work came out later in 1980.

At that time the west seemed to be much taken by Tibet, in this particular issue of the magazine, I would find two more comics themed around Tibet.

-0-

Previously:

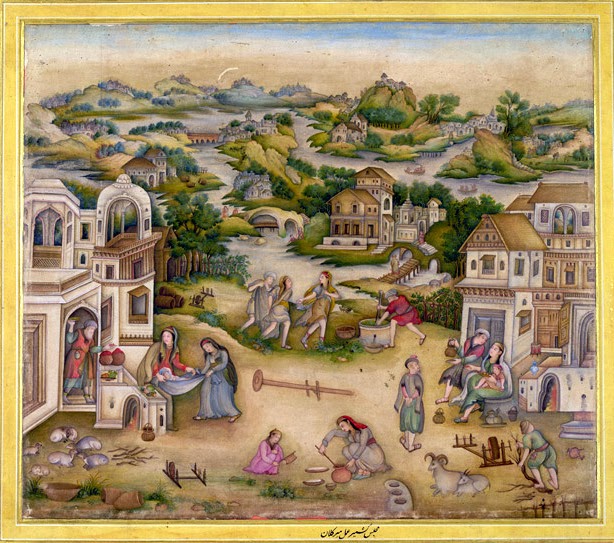

Kashmir in Indian Comics