Contributed by my Mamaji Roshan Lal Das. Lots of personal history and great insight on how a house was built in Kashmir. The photographs of the house were taken by me when I visited the place with my mother in June 2008 .

-0-

In the hoary past, most of the Kashmiri Pandits used to live in and around the dulcet and fertile area of Rajvatika, the present Rainawari. The Brahmins of Rajvatika exercised considerable influence during the period of late Hindu kings. During forties of 19th century, a family bearing surname ‘Choudhry’ lived in chodury bhag area of Rainawari.

It was the period of Sikh rule in Kashmir. One Hemant Choudhry of this clan left for greener pastures of Lahore. He worked as an accounts assistant to the father of a future prime minister of Kashmir. As years went by, Hemant became an ascetic and as his name spread, he was re-named Hemant Sadh by his Kashmiri neighbors who all lived in Kashmiri mohalla of Lahore, Sadh being the Kashmiri equivalent of Sadhoo.

Later on, with the initiation of Dogra rule, Hemant Choudhry, now Hemant Sadh relocated to Srinagar buying a House at Aga hamam in Habba Kadal. Hemant Choudhry had grown old. He went to his old boss whose son had now become Prime Minister – Dewan Badrinath, and asked for a job for his son Narayan Sadh. Narayan Sadh was offered a job as estate officer for prime minister’s landed estates. (Dewan Badrinath built a mansion in Kralkhod which was in ruins during my time and grabbed by one Wahab Makaya.)

Dewan Badrinath was not a Kashmiri and hence faced lot of difficulty in pronouncing the surname of Narayan Sadh. He suggested him to change his surname to Das. It was done and all the office records were changed accordingly. That is how my clan changed from Sadh to Das.

Narayan Das got married and had a son and a daughter but his wife died while delivering a third child. Days rolled by and Narayan Das was always on the move inspecting landed estates of his employer. He was now getting old. During those days fifty was considered old.

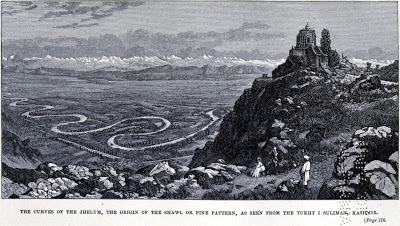

Harmiain is a sylvanic village in tehsil Shopian. It is lying at the plain of mountains leading to Aharbal and Kosernag Lake. The village is surrounded on all sides by a brook with icy waters.

Dewan Badrinath had huge landed estate in Harmain also and it was being looked after by a Rajput family (that grabbed it after his death). Once while touring this village, Narayan Das was bedazzled by the sight of a beautiful girl taking bath in a brook. She had perfect olive oil skin and a perfect complexion devoid of any swarthiness, which otherwise was believed to be the most common tone for villager people. The girl was seventeen and known as Haer – a bird which would mean Finch in English. The girls had been so named because of her impressive brown eyes. Proposals were sent to the girl’s parents through the emissaries. The girls parents were initially reluctant but in the end, being overwhelmed by the man’s status, gave in.

Marriage was solemnized with great pomp and show at Srinagar. Within couple of years Narayan was sent to Ladakh for survey of prime minister’s estates over there. It was not an easy task back then to travel all the way to Ladakh. Those days one had to travel on horses and the journey could turn dangerous. While returning from Ladakh, Narayan fell from his horse on the slopes of Zojilla Mountain. Hooves of horses broke his slide down the slopes but the fall caused him some severe injuries and by the time Narayan reached Srinagar, he had developed gangrene. He died and Haer became a widow by the age of nineteen. She was pregnant at the time.

Soon she delivered a male child who was named Shivji. This child was brought up with great care and love. He grew up, did his matriculation – which was a rarity and a feat those days. He became a Babu in the office of chief engineer Appleford. Shivji typed with great dexterity and a Remington typewriter could always be found by his side – his great personal possession.

In 1917, there was a great fire in and around Agahamam area of Habba Kadal. Shivji’s house too was engulfed in flames. Luckily the family had a chunk of land in Kralkhod .The mother and son started building a new house, this time on a much bigger scale. But when the work started Shivji was transferred to Ladakh. The widow had to build that house on her own. She put in all her savings into building that house. The house was complete at the end of year 1918 and it cost my great-grandmother all the savings of her life, around Rs.4000, a princely sum those days.

The house was nearly two thousand two hundred square feet in area and four storeys high – a massive building by modern standards. The foundation was laid in tonnes of broken stones. Those days Portland cement was a luxury that only a Maharaja could afford. The damp proof coating over the plinth was laid in form of wooden beams. In this case, the beams were nearly one foot by one foot thick and that too without hinges or knots. The pillars were raised in uneven stones joined in mud which with time turned out to be a major defect.

The upper storeys were built in thin square bricks which were known as ‘maharaji’ bricks which were supported by wooden beams. One room on the second floor was plastered with polished mud splattered with straw (I still wonder how they did it). And one room on third storey was polished in mud and somehow painted green, on completion this room offered a strange shine that exists even now. I still don’t know what sort of paint they used those days. This particular room was used as ‘Dewan Khan‘ – or the drawing room. The second and third storey had a retiring room which remained warm even in cold winters. These were called as ‘shainsheen‘ in Kashmiri.

The uppermost storey, as in most of Kashmiri houses, acted as summer retreat (Kay’nee in Kashmiri). The house had two balconies (zoon dab) which offered a panoramic views of Eastern Mountains and Northern mountains viz Mahadev peak, Zabarwan range and Shankracharya Hill in the east and Harmokh range and Hari Parbat hill in the north.

The uppermost storey, as in most of Kashmiri houses, acted as summer retreat (Kay’nee in Kashmiri). The house had two balconies (zoon dab) which offered a panoramic views of Eastern Mountains and Northern mountains viz Mahadev peak, Zabarwan range and Shankracharya Hill in the east and Harmokh range and Hari Parbat hill in the north.

In 1954, the zoon dabs were dismantled and a single elongated one was rebuilt instead. I had a narrow escape at the time of this renovation; a couple of bricks nearly fell on me.

Those days the roofs were thatched and waterproofed by birch leaves (known in Kashmiri as burza). As the clay turf turned heavy during rains and snow, tresses had to be very strong and weight bearing. To achieve this strength thick wooden plank transected by huge logs were used. These logs used to be almost a foot in diameter.

Those days when Deodar wood was cheap, the outer latticed windows, known as panjra in the local lingo, were built. The panjra work was an indigenous one. Laths were fixed into one another. No nails or glue was used as the laths supported each by exerting pressure on the wooden frame. A few wooden nails were used in some cases of thick laths. Years ago, I was surprised one day on seeing a small piece of paper ‘Times of India ‘ dated 1916, stuck to a panjra. The paper must have been glued there as insulation during severe winter of 1931, the year Jehlum completely froze. A few panjras still remained when we sold the house in 1975.

Those days when Deodar wood was cheap, the outer latticed windows, known as panjra in the local lingo, were built. The panjra work was an indigenous one. Laths were fixed into one another. No nails or glue was used as the laths supported each by exerting pressure on the wooden frame. A few wooden nails were used in some cases of thick laths. Years ago, I was surprised one day on seeing a small piece of paper ‘Times of India ‘ dated 1916, stuck to a panjra. The paper must have been glued there as insulation during severe winter of 1931, the year Jehlum completely froze. A few panjras still remained when we sold the house in 1975.

Years passed by and next generation viz my father and two paternal uncles shared the house. As often happens, there were frequent quarrels amongst them. The fights continued into my generation as well. Due to inherent defect in the founding pillars built up of uneven stones joined by mud, during Sixties, the house started bending from western side.

In 1973, a decision was taken to repair the house. It was a hard and a risky decision. The house could tumble down during repairs. An old carpenter, one of the carpenters who had built the Budshah Bridge, along with his brash young son took the responsibility of repairing the old house. Wooden poles nearly 30 feet in length were used as props (known as ‘pandas‘ in the local lingo). The ground floor was completely dismantled and the rest of the floors were now resting fully on these props. There was an earthquake once but the house managed to survive it. Four feet by two feet pillars were re-built in lime and brick powder. This combination of Lime and brick powder had been in use right from medieval period and I feel it was stronger than expensive cements of today. The lentils on the pillars were supported by wooden planks of hardwood known locally as Kikar.

It took nearly 6 months to repair the house. When the last prop was being removed the mason took to his heels. Later when we asked the reason, he said that he was not sure that the pillars will withstand the weight of the old building. The house was finally sold out to a rich boatman in year 1975.

In April 1993, I saw a photograph of our house on fire in the newspaper ‘Times Of India’. A timber seller in neighborhood had become a police informer (Mukhbir) Militants lit his store on fire which soon engulfed the whole neighborhood including our house. Luckily only the upper storey was burnt down.

The house was still standing tall when I last saw it in 2005 – a good eighty seven years after it had first been built by my great-grandmother.

Roshon, the great-grandson of ‘Haer’

June, 2010

The uppermost storey, as in most of Kashmiri houses, acted as summer retreat (Kay’nee in Kashmiri). The house had two balconies (zoon dab) which offered a panoramic views of Eastern Mountains and Northern mountains viz Mahadev peak, Zabarwan range and Shankracharya Hill in the east and Harmokh range and Hari Parbat hill in the north.

The uppermost storey, as in most of Kashmiri houses, acted as summer retreat (Kay’nee in Kashmiri). The house had two balconies (zoon dab) which offered a panoramic views of Eastern Mountains and Northern mountains viz Mahadev peak, Zabarwan range and Shankracharya Hill in the east and Harmokh range and Hari Parbat hill in the north.  Those days when Deodar wood was cheap, the outer latticed windows, known as panjra in the local lingo, were built. The panjra work was an indigenous one. Laths were fixed into one another. No nails or glue was used as the laths supported each by exerting pressure on the wooden frame. A few wooden nails were used in some cases of thick laths. Years ago, I was surprised one day on seeing a small piece of paper ‘Times of India ‘ dated 1916, stuck to a panjra. The paper must have been glued there as insulation during severe winter of 1931, the year Jehlum completely froze. A few panjras still remained when we sold the house in 1975.

Those days when Deodar wood was cheap, the outer latticed windows, known as panjra in the local lingo, were built. The panjra work was an indigenous one. Laths were fixed into one another. No nails or glue was used as the laths supported each by exerting pressure on the wooden frame. A few wooden nails were used in some cases of thick laths. Years ago, I was surprised one day on seeing a small piece of paper ‘Times of India ‘ dated 1916, stuck to a panjra. The paper must have been glued there as insulation during severe winter of 1931, the year Jehlum completely froze. A few panjras still remained when we sold the house in 1975.