The book “Kashmir: Exposing the Myth behind the narrative” (2017) is written by Khalid Bashir Ahmad, a former Kashmir Administrative Services person who served the State Administration in powerful positions as Director Information and Public Relations and Secretary, J&K Academy of Art, Culture and Languages, besides heading the departments of Libraries and Research, and Archives, Archaeology and Museums. The book, the latest fat brick targeted at Pandits, aims to prove that the whole Kashmiri Pandit narrative, ever since the beginning of history, is a bunch of lies, a “myth” and it goes about the task by masking anti-pandit propaganda as scholarship. In his zeal to write an all encompassing exposé, the author has unintentionally produced the finest document on what drives the anti-pandit sentiment in Kashmir valley and which class produces it for the gullible masses.

The book tries to settle the 1990 debate by trying to prove that Kashmiri Pandits have been a lying race since 6th century A.D., around the time Nilmata was written that too after annihilation of the Buddhist religion by “militant” Hindus. It’s does not try to debunk parts, it tries to do so the whole.

Khist-i-awwal chu nehad memaar kaj, Taa surayya mee rawad dewar kay

If mason puts the first brick at an angle, the wall, even if raised upto the Pleiad, is bound to come up oblique

Pandits claim to be “aborigines”. So, the first chapter is titled “Aborigines” dedicated to basically proving that Nagas did not exist. According to the writer if “Nagas” are disapproved, it can be proven the Pandits are lying. In trying to do so, it claims the no evidence of “Nagas” is found in neolithic sites like Burzahom. The thought that the snake worship cult evolved much later just does not occur to the writer. It claims that besides Nilmata and Rajatarangini, there is no mention of Nagas in context of Kashmir. The author ignores the fact that origin of

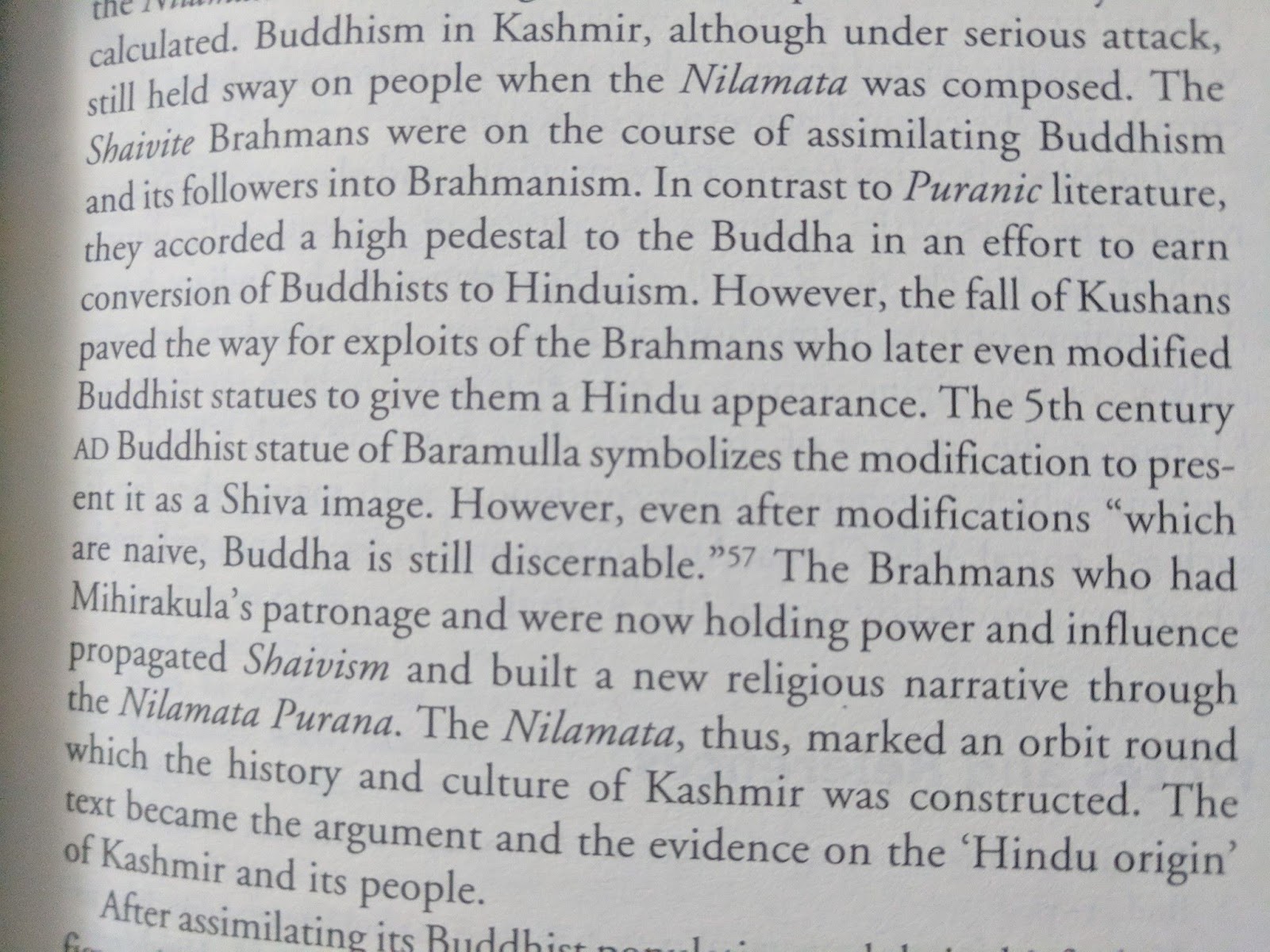

Buddhism in Kashmir also is based on the story of Nagas getting converted at the hands of buddhist monks. All buddhist sources on Kashmir mention the Nagas. The writer claims there is no archeological evidence of Naga worship when the fact is Pandits still worship the fresh water springs of Kashmir as Nagas and remember their deities. Ain-i-Akbari testifies to the fact that in Mughal times the snake cult was strong. The author does not mention the fact the snake deities are still worshiped a few miles away from Srinagar in Kishtwar valley. Instead it is hinted that the snake tales might have come from central India. The author doesn’t mention that Lalitaditya claimed descent from Naga dynasty of Karkota Naga. Even Chaks are said to have come from snake dynasty. Instead the reader is reminded that Buddhists were finished off by Brahmins. Here Kalhana’s account of Buddhist viharas is considered useful but in later chapter Kalhana is denounced as an unreliable source. The conflict between Hindu rulers and Buddhist rulers and subsequent destruction of viharas is read as a religious confrontation while the conflict between Muslim rulers and Hindu subjects and subsequent destruction of temples is never read a conflict between religions. The fact the in Nilmata, Buddha is celebrated is denounced by author as a sign of cultural aggression by Brahmins and not as a sign of cultural assimilation. That this assimilation meant that

Buddhism survived in Kashmir valley even till 12th century is ignored. The valley based readers of the book at are no point reminded at a lot of Masjids and Ziyarats in Srinagar as built upon Buddhist sites. No cursory mention of the fact that Jama Masjid of Srinagar used to be holy to Buddhist pilgrims even till 1950s. None of this is mentioned. Instead, the author writes:

“It is interesting to note that while many later Puranas and works such as those of Ksemendra, Jayaratha and Kalhana identify Buddha with Vishnu, all of them denounce Buddhism indirectly by assigning Buddha the task of deluding the people. The departure by the Nilmata in mentioning Buddha in a spirit of catholicity looks calculated. “

Here the author exposes his lack of knowledge of history he has embarked upon exploring. He forgets that Ksemendra himself was a Buddhist. In his works he presents most religious men as charlatans, even Buddhists but particularly the Brahmins. In Kashmir back them, men were still free to speak their mind against hypocrisy and dogma of religious men. Instead, the author is too focused on proving that writers of Nilmata were “calculating” brahmins. This “Eternal Pandit”, mean, calculating, power hungry, back stabbing, money grabbing is the running theme of the book.

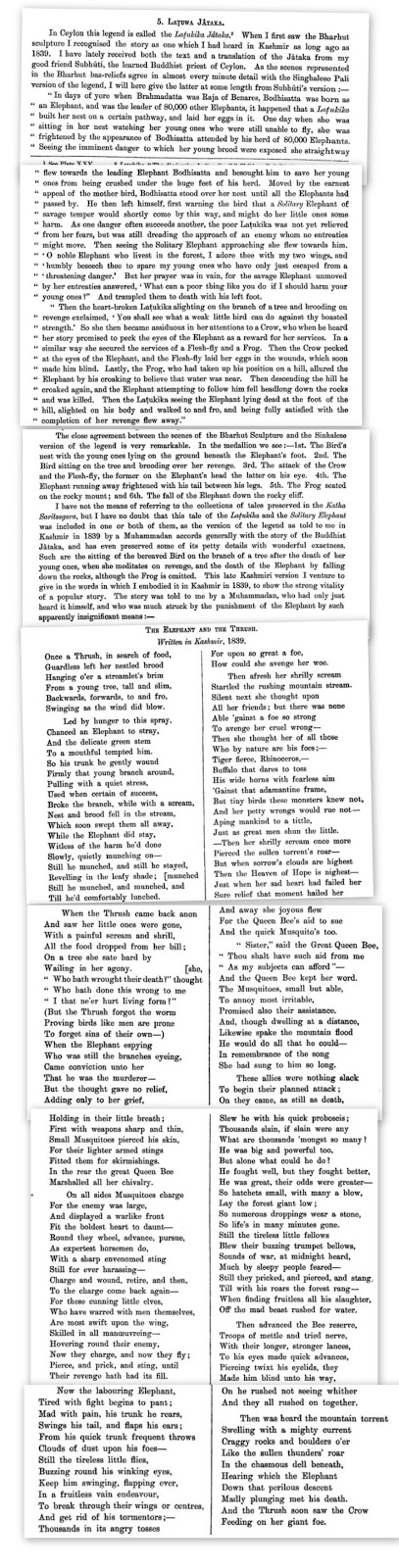

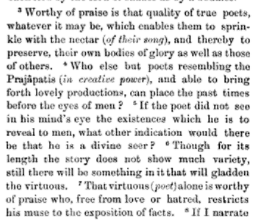

In the next chapter titled “Mind’s eye” the author tries to prove that Kalhana was again a lying brahmin. According to the author, Kalhana in his own words used “Mind’s eye” to write the history of Kashmir, the author writes the entire chapter under the impression that “Mind’s eye” means some sort of divine intuition to write about past that Kalahan had no access to.

The author’s understanding of theory of history is so rudimentary, his approach so flavoured with politics of present times that he does not even realize the utter nonsense he has presented through partial quotes cooked in furnace of deliberate malice . No, Kalhana did not use “Mind’s eye” to write about prehistoric Kashmir. Kalhana mentions “mind’s eye” in context of definition of purpose of a poet. The “mind’s eye” is the plane of the brain that gets triggered when one reads something that stimulates one’s imagination.

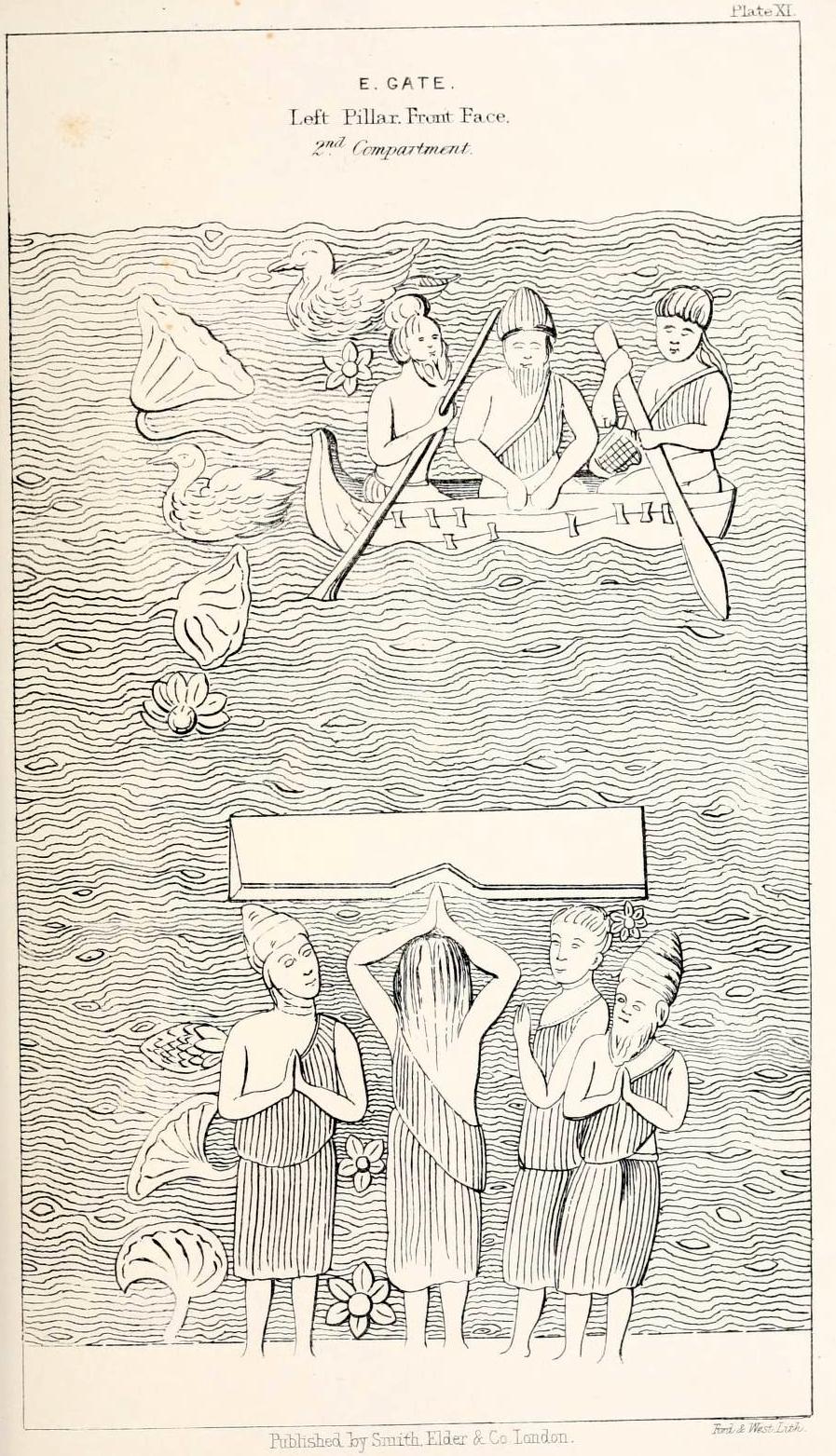

|

| Kalhana describing the purpose of a poet writing about histroy |

Kalhana mentions that it is the job of a poet writing history to bring alive history. That it should be written in such a way that the the story plays in the mind of the reader and this is not possible unless it runs alive in the “mind’s eye” of the poet first. He mentions that a poet of history should not just state facts but tell a story, an unbiased story. Rajataragnini is deliberately written by him in “Santa Rasa”. Of course, the author had no clue or no inclination to inform his readers all this. Rajatarangini is written based on theory of Sanskrit literature. “Santa Rasa” or the Rasa of peace is used to offer solace to the world weary mind of the powerful people who read it. The whole Rajatarangini is written with a sense of resignation, that all good things as well as bad things pass. It was for this reason that the leaders like Budshah, Akbar and even Nehru studied and found solace his work. It presents to “mind’s eye” the story in which the power is shown to be ever transitory. But some people have their “mind’s eye” so blind shut, they can’t see all this. The fact that he have an entire chapter on Kalhana titled “Mind’s eye” makes the author’s ignorance about the meaning of the term all the more hilarious. The reader is not told the Kalhana told the story based on still older texts, even a text of history written by Kshmendra. The reader is not told that history of Kashmir was already known to Mughal world based on Persian translations of Rajatarangini and various other works. The discovery of Rajatarangini manuscript in Kashmir was celebrated because now people had direct access to the source. If there was no Rajatarangini, if the Pandits had not kept it safe, how else would we have known how about the past of Kashmir?

Instead, in this book Kalhana’s mind is targeted as if it it was mind of a delusional brahmin who knew in future Muslims of Kashmir would be bothered by his writings.

“Kalhan was not a man with a closed mind, and this after all, is an essential qualification for a good historian.” …and that’s a quote on Kalhana’s mind from Romila Thapar.

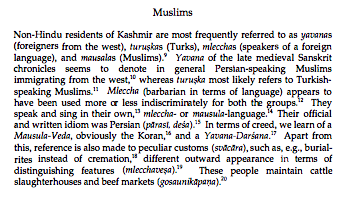

In the next chapter titled “Malice”, the reader is basically told that Jonaraja was again a malicious Brahmin. According to the author, Jonaraja was a man who hated Musalmaans, why else would he not use the word “musalmaan” even though the word existed as proven by famous Lal Ded saying “na booz Hyund ti Musalmaan”. Genius! The thought that the saying is of obvious later origin just doesn’t occur to the director sahib of historics even though he does quote Chitralekha Zutsi. The reader is not told that the word “mausala” does infact figure in Rajatarangini post Kalhana, instead the reader is confused with words like “Yavanna” and “Mleecha”, not told that even word “Yavanna” is used with beauty by Jonaraja when he describes Muslim/Yavana worshipers as “…crowds of worshippers used to fall down and rise at prayers, imitating the high waves…”

Walter Slaje, the Austrian expert on medieval history of Kashmir and Rajatarangi explains the usage of these terms like this:

So, the reader thinks Jonaraja, he too was a lying Brahman who told lies about Sikandar just because Jonaraja couldn’t reconcile to the fact that the Hindu era of Kashmir was over. Some one teach director sahib about how not to read the past through the lens of present, lest someone claim that director Sahib is making the claim cause he can’t reconcile to the fact that Kashmir is right now partly ruled by Hindu BJP. It’s like saying that historians-artists of Kashmir will start to invent myths at the first sign of majority religion losing hold of business of running State. Err…isn’t that happening in Kashmir. [the usual reply from Kashmir: a muslim would never do that, only pandits can]. It would also mean that any Pandit rejecting the claims of the book about Jonaraja or Kalhana is obviously doing so because of what happened to him in 1990, and hence is lying. What buffoonery passes for history in case of Kashmir!

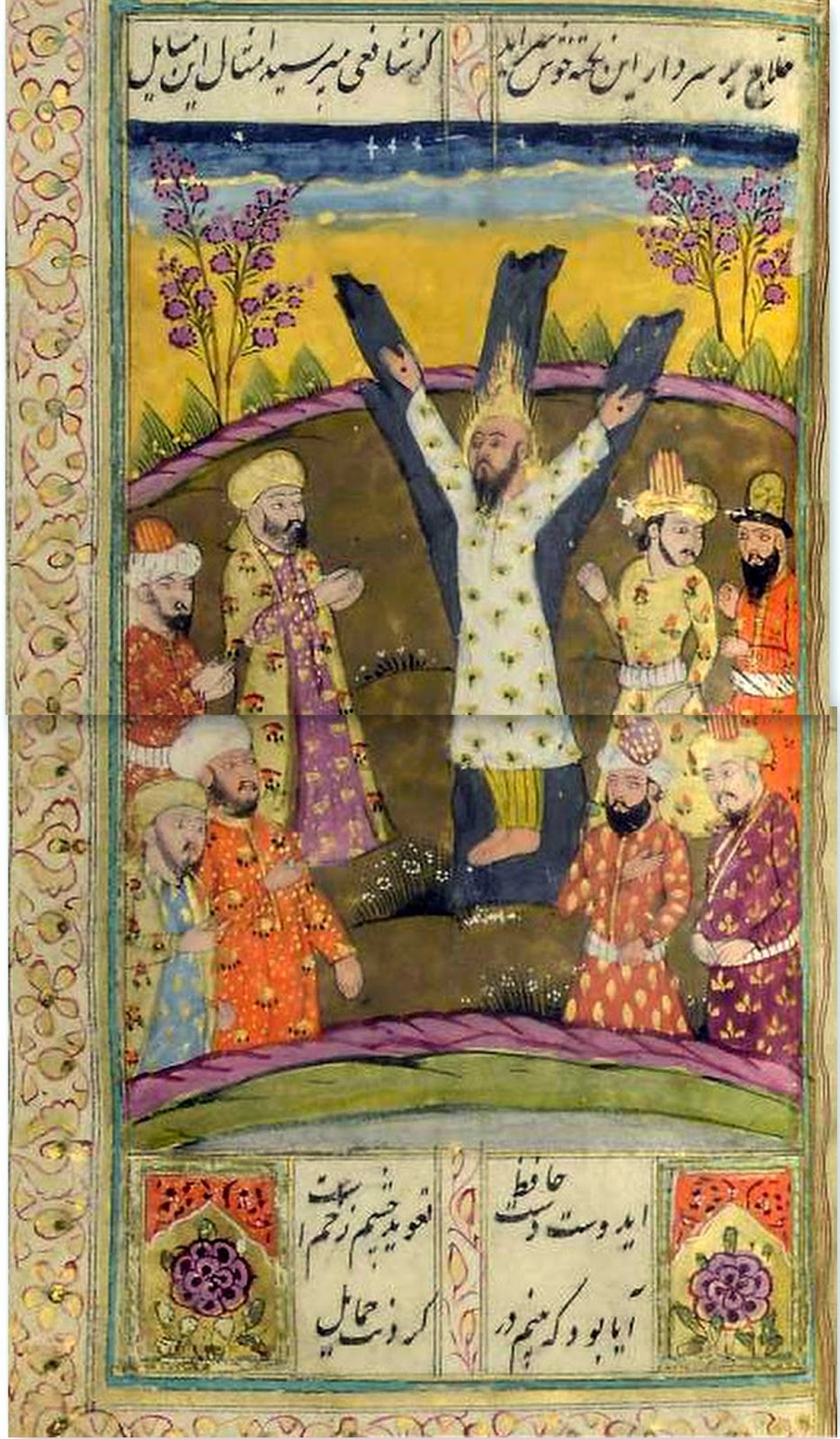

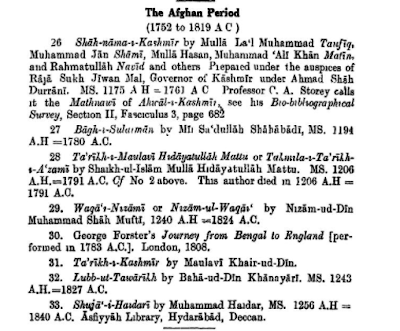

The author claims Kalhana was a essentially a poet and a believer of fairytales and hence can’t be trusted, Jonaraja hated Muslims, hence can’t be trusted. But, in this chapter while mentioning the faults of Jonaraja, author asks why Jonaraja didn’t mention Hallaj’s visit to Kashmir. There is a widely and newly found belief in Kashmir that Mansur al-Hallaj (857-922) visited Kashmir in 896 AD. The source of the claim comes from “The Passion of Al-Hallaj: Mystic and Martyr of Islam by Louis Massignon” translated and edited by Herbert Mason (1982/94). Massignon’s work was translation of 13th century manuscripts of “Tadhkirat-ul-Awliyā” (Biographies of Saints) by Attar of Nishapur (1145). Attar was essentially a poet, here the Kashmiri author would like to trust the words of a poet who wrote about miracles performed by Sufis. Interestingly, in the same work of Attar, we read about Kashmiri slaves serving missionaries in Persia. Author ignores all this. [Read: Hallaj in Kashmir]

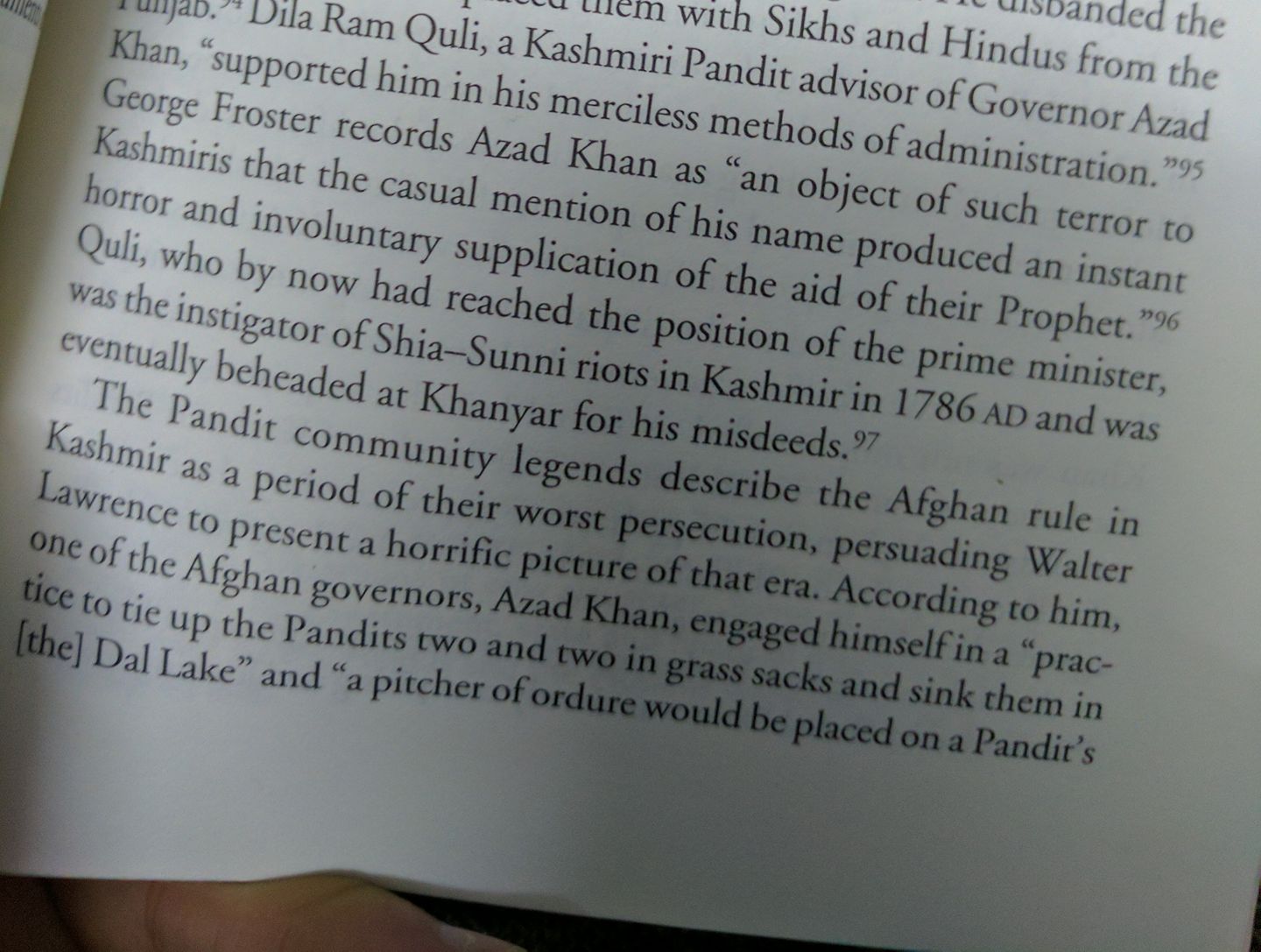

The next chapter is titled “Power” and the reader is reminded that Pandits were part of the Power circle during Afghan rule. That Pandits invented the stories of persecution.

This chapter on Afghan period in Kashmir ends with reader being told that a pandit was responsible for Shia-Sunni riots and probably was the cause of debauchery of the ruler. Then the reader is told that pandit masses suffered no brutality under Afghans….after all pandit were working for Afghans on high posts. The pandit were again lying. It was pandits who convinced Walter Lawrence to write those horrible things about Afghans. Hence proved: Pandits the perpetual liars and power hungry fiends . He then goes on to quote a pandit…Birbal Kachru’s work to prove that only Muslims (Bombas…readers are not told that Bombas were Shia) suffered under Afghans. Rest is all figment of imagination – “mind’s eye” – of later Kashmiri pandit writers.

In all this the facts reader in Kashmir is not told:

Lawrence based his writing on Peer Hassan (1832-1898) and not some pandit. It is not as if Pandits poisoned Lawrence’s ears against Muslims. Hassan has written at length about it in his “Tarikhi-Kashmir”. Interestingly, the “historian” makes no reference to Hassan in this section.

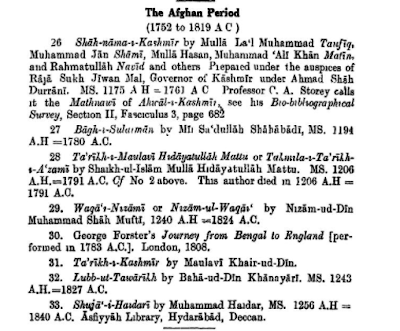

Reader is not told that GMD Sufi, again a Muslim, in 1949 in his “Kashir A History Of Kashmir” wrote at length about the tyrannical Afghan period and mentions persecution of Hindus as well as Shias. Sufi does not use Kachru as source for Afghan period but uses him for Sikh period during which he lived. For Afghan period he uses Muslim sources, works of afghan era, all of which mention persecution.

|

| Sources used by GMD Sufi. |

And finally if someone working for Afghans at high post means it was all peaceful back then for the rest of the community, surely the author of this tome himself working as a government employee for Government of India in 1990s should be read as benevolent nature of the government and a general sign of how peaceful the 90s were.

In between, innumerable inanities, the book also reminds the reader of valley that Kashmiri Pandits are different than rest of Hindus. Proof: Krishna cult had no presence in Kashmir. There are no Krishna statues or temples in Kashmir. The reader is here not told that Kalhana starts his Rajatarangini with mention of Krishna in relation with King Gonanada. The reader is not told that exclusive elaborate Krishna sculptures across India are a recent phenomena. Before that there was more elaborate Vaishnav cult theories centered on various avatars of which many are now considered minor. The reader is not told of the “flute player” on the walls of Martand.*

Why does author bring it up? Because in 1980s, Kashmiri Pandits publicly started celebrating Krishna Janamashtami and the Kashmiri fundamentalists cum conspiracy theorists saw in it the attempt of Kashmiri Pandits aligning with alien “Indian culture”. In such attempts these fraud “intellectuals” try to dictate who is a good native Kashmiri Pandits true to Kashmir and who is bringing in Indian Culture. Back in 80s, all such Indian Kashmiri Pandits were branded Sanghi Pandits.

In the beginning of the same chapter, we are gratuitously told of poet Sir Muhammad Iqbal’s thoughts on pandits of valley:

A’an Brahman zaadgana-e-zindah dil

Laleh-e-ahmar zi rooye sha’n khajil

Tez been-o pukhta kaar-o-sakhy kosh

Az nigah-e-sha’n farang andar kharosh

Asl-e-sha’n az khaake-e-daamangeer ma’st

Matla-e-ein akhtara’n Kashmir mas’t

These scions of Brahmins with vibrant hearts,

their glowing cheeks out the red tulip to shame.

Keen of eye, mature and strenuous in action,

their very glance puts Europe into commotion.

Their origin is from this protesting soil of ours,

the rising place of these stars is our Kashmir.

It appears that Iqbal loved Pandits and his took pride in his pandit origins. Later as the author unleashes his propaganda against Pandits, the reader has no option but to think of Pandits as ungrateful people.

Hai jo peshani pe Islam ka teeka Iqbal /

Koi Pandit mujhey kaihta hai to sharm aati hai.

The mark of Islam is on my forehead

I am ashamed if someone calls me a Pandit

The reader is not told that Iqbal of later age,

lauded a murderer like Ilam Din and laid the ideological foundation of religious state called Pakistan. If poet Kalhana’s poetic genius should not cloud our opinion about his ability to be neutral, or just his politics, why should any other parameter be set for Iqbal? Why expect pandits to celebrate Iqbal? (

another pet peeve of the author of this book)

In the next chapter titled “Blood”, we move to Dogra times. Somewhere, the story of Pandits refusing Muslim “gharwapsi”, a initiative of Dayanand Saraswat is repeated by the author. The author repeats the claim just as it is made by Hindutva people, particularly Balraj Madhok.

Using such spins, the pandit are mocked by Sanghis as well as Islamists for being too “proud”. The eternal “proud” pandit.

In this chapter, the reader is reminded that Pandits have muslim blood on their hands and they no Pandit was harmed in 1931. That there were no riots against Hindus. That muslims hands were always clean of any blood.

To that I can offer some personal history:

I called my grandmother this morning to ask her again the story.

I call to ask her the name of the man who died in 1931. Morning of July 13th in Kashmir.

She asks me not to waste my time.

I insist.

He was a brother of her mother.

She doesn’t remember the name. She doesn’t remember the year. What did he do for a living? She doesn’t know.

All she knows:

‘It was the year of first “gadbad“.’

I remember hearing bits: He had gone out to get bread from the local bakery. Someone put an axe to his head.

She doesn’t remember all this.

She asks me not to waste my time with this nonsense.

She asks if I had my breakfast.

The next chapter “Agitation” deals with Parmeshwari Handoo case and is interesting as it quotes old local newspaper reports and rightly links the case to rise of Jan Sangh in Kashmir. In this chapter too you will read a Pandit saying some nice things about Jamaat-i-Islami and bad things about Jan Sangh. The book practically is based on the now established textual norm of quoting Pandits to prove Pandit are lying hence tahreekis are telling the only truth. One truth. Readers are reminded by author that inter-religion marriages had previously taken place in Kashmir but there were no communal disturbances. In horde to provide examples of communal harmony, we are told artist Ghulam Rasool married a Pandit girl Santosh Mehra. Fact: Santosh was not a Kashmiri Pandit and Ghulam Rasool was hardly the “ideal” muslim. Why only in Parmeshwaru Handoo case did Pandits came down on streets? Long quotes are provided linking Pandit community en-mass to Jan Sangh. Pandits planning acid attacks, arson attacks and desecrating muslim mosques. Authors uses official police records here.

The reader has no option now but to see Pandit as the perfect enemy.

Fact: Such communal polarizations and crimes are more often than not two sided affairs. How is this act of compilation different from a Hindu organization compiling a list of FIRs naming just Muslims during a riot? To what purpose are such listings used. But, people in Kashmir as so used to their majority status, such questions just do not bother the author.

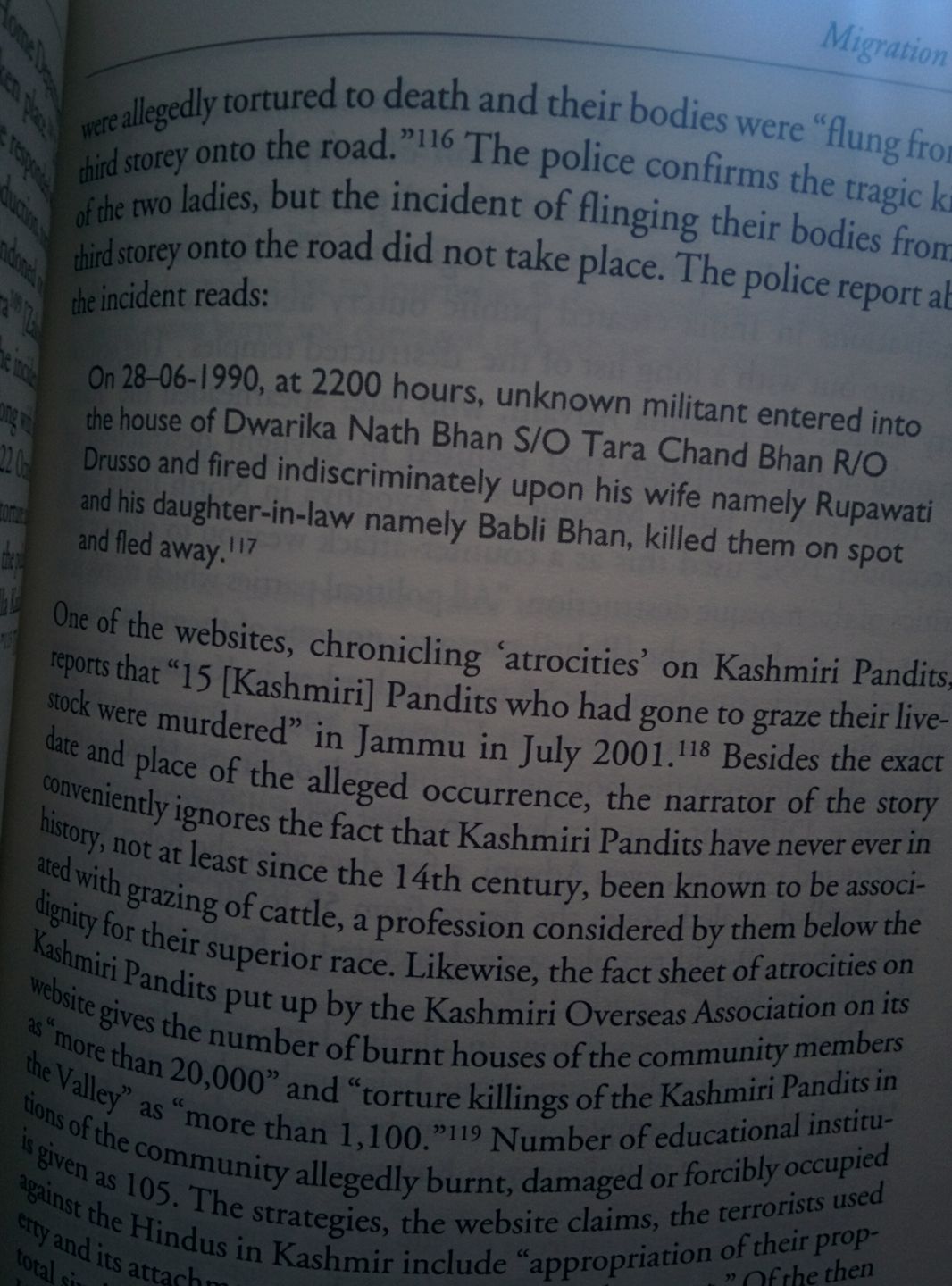

The real tragedy of Kashmiri Pandits is that this is probably the first book that actually has the exact FIRs of their dead and their raped, and some new names . It is another matter that that are used to forward the usual: 1. Not enough died. 2. Pandits [like their ancestor Kalhana] exaggerated the description of scene [no, no, not like people that did it in case of Asiya-Neelofar in 2009, ignoring the FIRs when needed. Is the official police report of Kunan Poshpora acceptable to the author?

Guess being Director of something in government has its perks. The modern brahmins…those that control the texts…control history. But, I guess most Pandits would thank this book for giving out those FIR details.

In case of Bhan family, using an RTI, the writer finds that the killing did happen and then claims the gruesome details of the killing, flinging from the top floor, were figment of KP minds as the police report don’t offer any detail. Earlier he has already tried hard to prove that either KP killings were carried out by State or for being “informers”. Why now he feels the need to prove that killings were not “gruesome”? Guilt. All proof need to be erased. All blood stains wiped clean.

He then proceeds to expose “Pandit” propaganda using a quote from a Hindutva site to prove that KPs have never ever, never ever, never ever since 14th century, fed the cows.

Most of the killings of minorities in Jammu and Kashmir have been “adopted” online by Hindutva sites. No, you won’t find any neutral site easily with clear data and facts. On hindutva sites written by non-Kashmiris, regurgitation of data has high amount of mutation. Which leads us to this comedy of fools: The professional KM “historian” reads a “fact” and then in his expert 14th opinion decides to cook pandits in a medieval oven of fresh “facts”.

He writes that the hindu propaganda site claims:

“15 [Kashmiri] Pandits who had gone to graze their livestock were murdered ”

He then informs the readers that the elite Kashmiri Pandits never have taken cattle for grazing, ever! That’s all he could come up with to cast the spell of doubt on the killing! So Kashmiri Pandits didn’t die because Pandit wouldn’t touch the job. The discussion ends up about “status” of pandits in ancient Kashmir.

The fact:

The hindutva site mentions: “15 Pandits who had gone to graze their livestock were murdered ”

The “historian” added the word “Kashmiri” to it and started discussing cattle grazing habits of Kashmiri pandits.

The fact: The killing did happen. It was not Kashmiri Pandits. But 15 Hindus of Chirjee near Kishtawar in Doda who were killed by terrorist. The entry for it in not found on any Indian government site online but in US congress report on Human rights.

It didn’t occur to the “historian” (and wouldn’t probably to his readers in Kashmir) that in villages, Pandits used to have cows at home, and like any other villager, this pandit too used to take his cows from grazing. See…now we are talking cow. Isn’t that how most discussions end up these days? Utter ludicrous diversions that don’t allow you to get to the facts.

In dealing with exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990, reader is told using account of Muslims that Pandits left Kashmir in aeroplanes. The usual Jagmohan Conspiracy is forwarded as the culmination of centuries old cruel games that pandits like to play.

Why was this book written the way it was: rejecting Nilmata, Rajatarangini, Afghans brutalities, 1947, 1967, 1986, 1990?

It was done so because Kashmiri Pandit tell their story in that sequence. Pandits claim to be “aborigines”, claim Rajatarangini as “their” history, claim they suffered under Muslim rule, suffered losses in 1947 partitions, were beaten to ground politically in 1967 agitation over “Parmeshwari Handoo case”, suffered rioting in 1986 in Anantnag and were finally forced to flee in 1990.

It’s an infantile game the two sides are playing. Pandit brains wanting to explain 1990 by explaining Sikander. Muslim brains wanting to negate 1990 by negating Sikander. In between always quoting Lal Ded as some symbol of peace. One side claims C is true, then B is true so A is also true. Other side counter claims as A is a lie, so B is a lie and then C obviously is a lie too. No side ready to accept that lies are being peddled left, right and center. And yes, don’t forget pandits are greater liars because in Muslim books you will always find pandit forwarding the “Jagmohan theory”. This book even quotes actor Rahul Bhat saying something like “I accept KMs suffered more than KPs.” Basically, the fact that a KP would empathize with KM is also used as a handy tool when needed. Don’t be surprised if you see less KPs making such claims in future. Don’t be surprised if the chasm between the two communities increases. And don’t be surprised to see which class politically befits from it in India and in Kashmir valley.

-0-

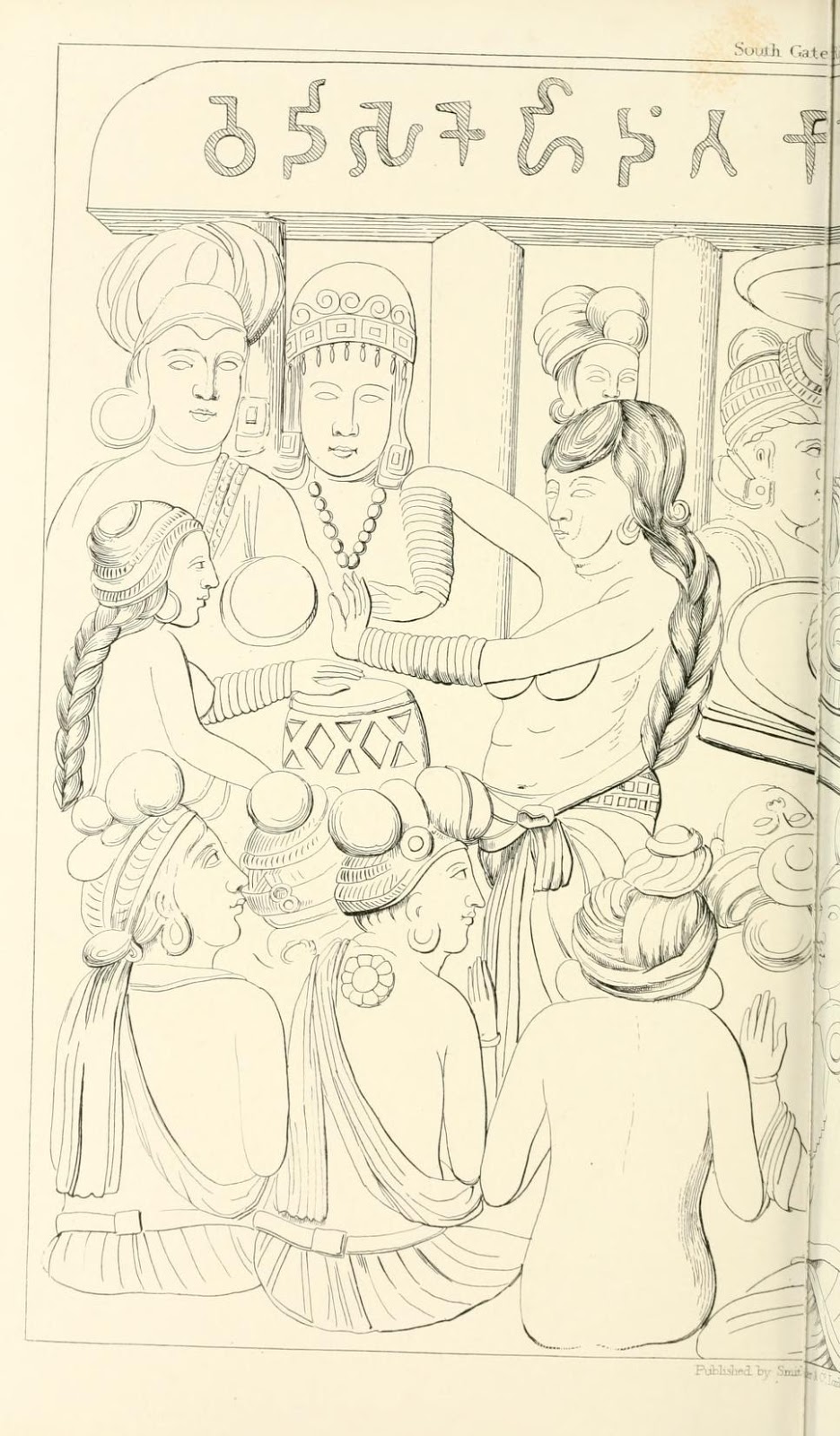

*The Flute players. It is wrong to thing of this image as Krishna. If you are Hindu, if you accept rest of my arguments, if you don’t understand the or know the subject enough, there is a good chance you will accept this as evidence. This is confirmation bias. The bias with which this whole book is written. A muslim reader of the book would have tough time acknowledging it.

The image of Krishna dated 1/2 nd century A.D is infact found on a boulder in Chilas (POK) along with that of Baldev and even Buddha. A Pakistani expert of Kashmiri origin, A. H. Dani mentions it in his “Chilas: the city of Nanga Parbat” (1983).

-0-

Some more lies from the author:

According to Bashir, cunning Brahmins modified (disfigured) Buddhist statues to give them Hindu look. He calls it Buddhist statue…not Gandhara statues. Bashir calls it “5th century Buddhist statue.”If one reads what he has written…there is only one conclusion that a lay reader in Kashmir with no real access to Hindu culture or original sources would assume: Brahmins mutilated Buddhist statues to make them Hindu. He bases his claim based on writing of Aijaz Bandey about an Ekamukha Shivling in a temple in Baramulla. Something he reveals (rather hides) in bibliography. And if one actually reads Bandey about that Shiv ling…we read something else completely. We read about how Gandhara art influenced Hindu art in Kashmir. Bandey does not make it sound like Hindus disfigured Buddhist statues to make Hindu gods out of them. Bandey writes about art assimilation. He even accepts there were already such Hindu images in Gandhara. Khalid Bashir Ahmad’s skewed logic if one extends to Muslim art in Kashmir, all Kashmiri traditional Muslim Ziyarats are Buddhist and not just influenced by Buddhist art.

Also, if one knows the basic history of Kashmir…one would know that Mihirkula brought in priests from Gandhara in Kashmir…something that local priests resented. How are these foreign priests supposed to have created a highly localized document like Nilamata?

Example of how the text from Bashir’s book is getting used for propaganda online. The section on left occurs in Bashir’s book.

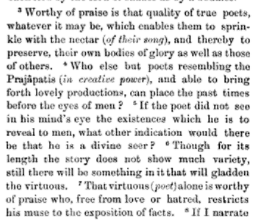

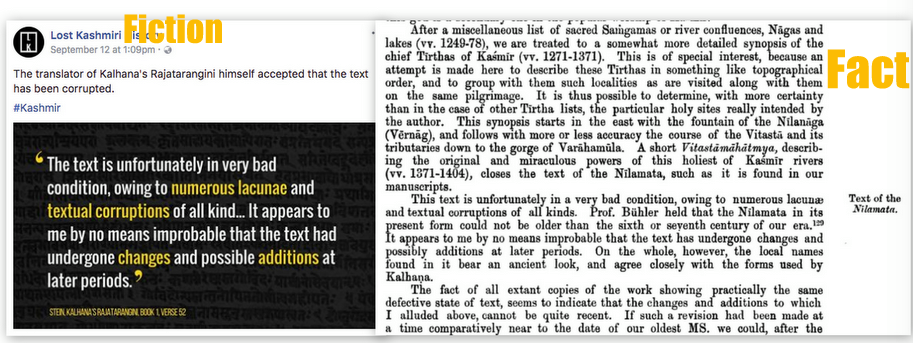

Propaganda: Stein thought Kalhana’s text was corrupted.

Fact: On page 377 of “Rajatarangini: a chronicle of the kings of Kasmir, Volume 2” Stein is infact talking about the condition of a manuscript of Nilmatapurana found by Georg Bühler. More particularly, Vitastamahatmya. Not Rajatarangini.

Fact: Stein spent his life proving the merit of Kalhana’s Rajatarangini in historical sense by mapping its text to real places, real people as mentioned on coins and inscriptions on sculptures/temples.

Fact: Had manuscripts of Rajatarangini and Nilmatapurana perished like rest of ancient manuscripts of Kashmir, had some families not preserved, our knowledge of old Kashmir would have been next to nothing. Your ultra-nationalistic pride of having thousands of year old history would have been just hot air.

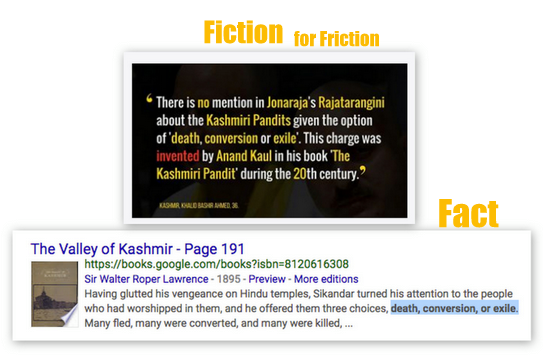

Another use of the quotes from Bashir’s book used for online propaganda. Here again, Bashir’s ability to lie would amaze anyone who has actually read the sources.

Anand Kaul wrote ‘The Kashmiri Pandit’ in 1924. Lawrence used the term “death, conversion or exile” already in 1895. But, of course, the propagandists know most people in Kashmir would easily accept that a Pandit lied being “Brahman Qaum”.

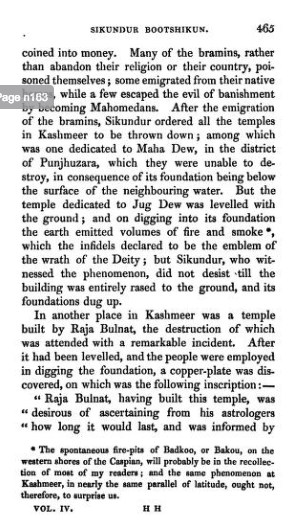

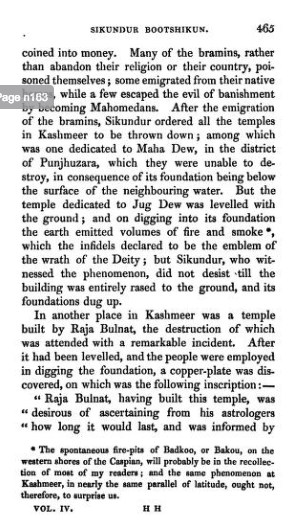

Fact: “Butshikan” term for King Sikandar was used by Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah for his Tarikh-i Firishta (1612). And he mentions the persecution of Hindus. It was not Kashmiri Pandits who invented the term. It was British to first latched on to the term. Anand Kaul only followed their lead. Unlike Bashir he had no access to Google, to know better. Postcolonialism hadn’t yet arrived.

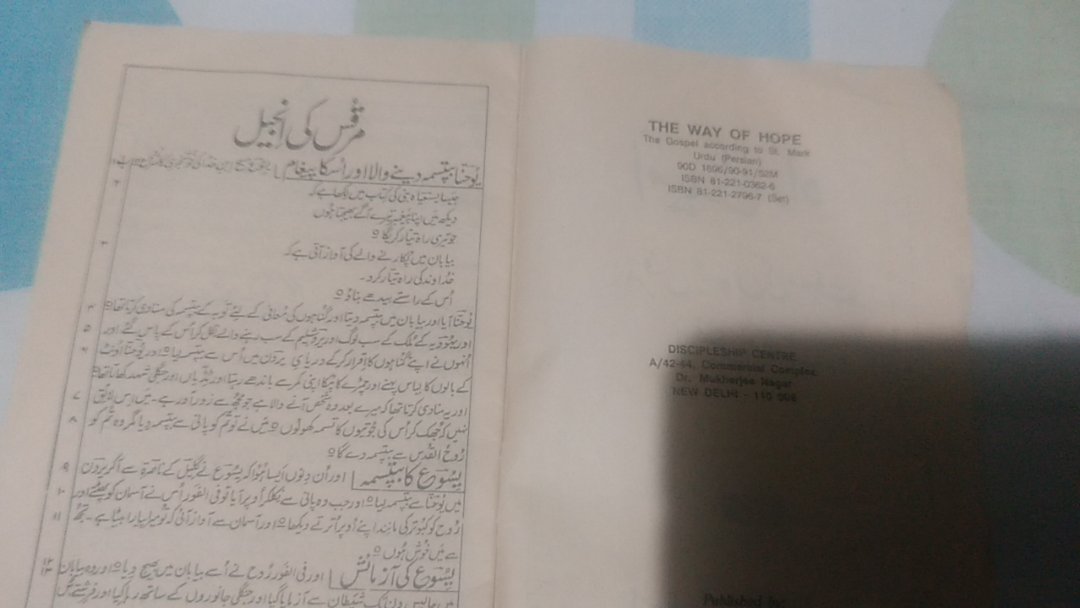

|

| “History Of The Rise Of The Mahomedan Power In India Volume 4. Enlish translation by John Briggs 1831. |

Fact: Jonaraja does mention that Sikandar did towards the end of his life change his ways. Jaziya was stopped.

Fact: Toward the end of Sikandar era we do find an old sculpture of Brahma that in Sharda has an inscription with name of King Sikandar on it, having being commissioned by a Hindu/Buddhist officer of the king.

-0-

Another example of these half-educated charlatans befool the people. Clearly, the author has no actually understanding of the history of Shaivism in Kashmir. He is out of depth here, and yet he does not shy away from making a fool of himself. Here again, the reader is reminded that even Shaivism was a relatively recent import from mainland India by clever, deceitful, exploitative Brahmins. In his frenzy, the author ignores the actual facts and instead invents another lie: Tryambakaditya settled in Kashmir in 800 A.D.

Fact: Sangamaditya, the 16th descendant in the line of Tryambaka settled in Kashmir in 8th century. His father Tryambaka XV married a brahmin woman in Kashmir. In that he broke the the celibacy tradition of the “Siddhas” all of whom were given the title “Tryambaka”. The matrilineal society of Kashmir demanded that Tryambaka XV’s son settle in Kashmir. So, Sangamaditya the 16th descendant in the line of the mythical original Tryambaka settled in Kashmir.

Somananda, 4th descendant of Sangamaditya produced Shaiva literature (Sivadrsti) in 9th century.

[ref: Śaivāgamas: A Study in the Socio-economic Ideas and Institutions of Kashmir by V. N. Drabu]

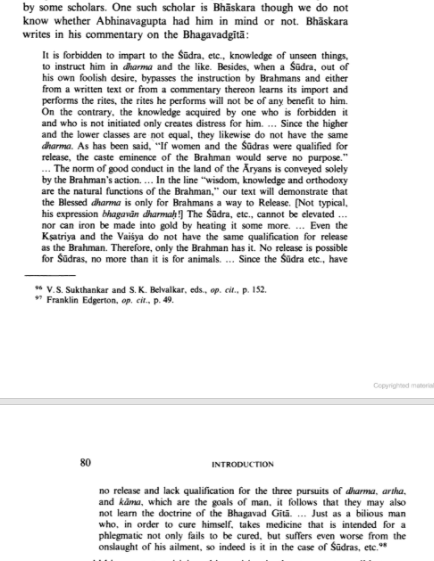

Fact: This is how most famous Kashmiri Shaivite Abhinavagupta (c. 950 – 1016 AD) in his Gītārthasaṅgraha was re-interpreting “divine word of god” Gita to make the text more inclusive. This is how the ideas of Shaivite in Kashmir, were setting ideological base for coming of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi who would see all humanity as one. It was in a way Shaivite and their monotheism that made Islam not a completely alien thought for the masses in Kashmir.

Anyone who has actually read Trika system would know that Saiva system looked down upon temple worship, daily rituals of brahmins and even the Vedas were treated as inferior knowledge.

Yes, Kalhana and Kshemendra mock the priests and pretenders. That tells us even back then, just like now, there were charlatans. Even, Noor ud-Din Noorani in his time mocks the Mullas and their exploitative ways. This also tells us that back then Kashmiris had a culture of criticism. A culture that is missing in missionaries that arrived in Kashmir later.

The Mullas flourish on money

fests

These Sheikhs like honey

stick to wealth

The sufis half-naked

do no work

yet, enjoy

unrepentant

many scrumptious meals

None pursue knowledge,

It’s all just another game

these selves

unrestrained

Seen them lately?

Catch them live

Try this old trick:

Announce a grand feast,

from pulpit

now watch

This Mulla run to the Masjid

“Run sick Mulla! Run!

Run to your Masjid.”

These are the words of the saint of Kashmir, after whom the Srinagar airport is named ( built on a Karewa named after a Naga, Damodara).

090