|

| Shalimar Ghat Road By By Samuel Bourne. ~ 1860s |

|

| Shalimar Road, Feb, 2014. |

-0-

in bits and pieces

|

| Shalimar Ghat Road By By Samuel Bourne. ~ 1860s |

|

| Shalimar Road, Feb, 2014. |

-0-

|

| Goddess of Dance, Indrani 7th Century, Kashmir Sri Pratap Museum This Goddess of Dance, Indrani 7th Century, Kashmir Sri Pratap Museum This one was came from Badamibagh in 1926. About 20 other were found in Pandrethan between 1923 and 1933 while digging of military barracks were going on in the area. More than 500 relics were found. Now not much remains. |

|

| Kashmiri Dancing Girl at Shalimar photograph by Herford Tynes Cowling, for National Geographic Magazine, October 1929. |

|

| Vyjayanthimala in Amrapali inserted into a comic panel based on story of Hamsavali from Somadeva’s Kathasaritsagara. Somadeva, son of Brahman Rama, composed the Kathasaritasagara (between 1063 and 1081) for Queen Suryavati, daughter of Indu, the king of Trigarta (Jalandhar). She was the wife of King Anantadeva, who ruled Kashmir in the eleventh century. The story of Suryavati, Ananta, Kalsa and Harsha is perhaps the gruesomest tale from Rajatarangini that ends with Anata killing himself by sitting on a dagger and Suryavati going ablaze. |

-0-

2017

-0-

Update:

This video was made by explorer Capt J. J. Noel, famous for his 1922 and 1924 expeditions to Mount Everest.

As stood on the ancient terrace, a little girl walked unto the place where I stood, confident, she went, ‘Execuseme!’. I realized I was blocking the entry to the monument. The right thing to do is – walk aside.

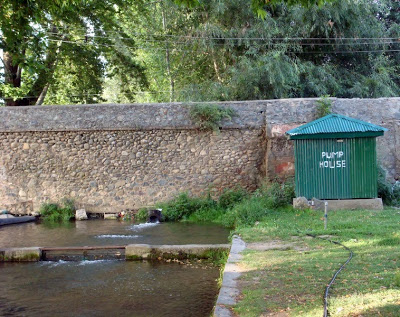

Alternate entry point. No entry fee. And it is fun. Again, stupidly enough, it was not included in the original garden plan by the great Mughals.

The famous Shalimar Bagh lies at the far end of the Dal Lake. According to a legend, Pravarsena II., the founder of the city of Srinagar, who reigned in Kashmir from A.D. 79 to 139, had built a villa on the edge of the lake, at its north-eastern corner, calling it Shalimar, which in Sanskrit is said to mean ” The Abode or Hall of Love.” The king often visited a saint, named Sukarma Swami, living near Harwan, and rested in this villa on his way. In course of time the royal garden vanished, but the village that had sprung up in its neighbourhood was called Shalimar after it. The Emperor Jahangir laid out a garden on this same old site in the year 1619.

A canal, about a mile in length and twelve yards broad, runs through the marshy swamps, the willow groves, and the rice-fields that fringe the lower end of the lake, connecting the garden with the deep open water. On each side there are broad green paths overshadowed by large chenars ; and at the entrance to the canal blocks of masonry indicate the site of an old gateway. There are fragments also of the stone embankment which formerly lined the watercourse.

The Shalimar was a royal garden, and as it is fortunately kept up by His Highness the Maharaja of Kashmir, it still shows the charming old plan of a Mughal Imperial summer residence. The present enclosure is five hundred and ninety yards long by about two hundred and sixty-seven yards broad, divided, as was usual in royal pleasure-grounds, into three separate parts : the outer garden, the central or Emperor’s garden, and last and most beautiful of the three, the garden for the special use of the Empress and her ladies.

The Shalimar was a royal garden, and as it is fortunately kept up by His Highness the Maharaja of Kashmir, it still shows the charming old plan of a Mughal Imperial summer residence. The present enclosure is five hundred and ninety yards long by about two hundred and sixty-seven yards broad, divided, as was usual in royal pleasure-grounds, into three separate parts : the outer garden, the central or Emperor’s garden, and last and most beautiful of the three, the garden for the special use of the Empress and her ladies.

The outer or public garden, starting with the grand canal leading from the lake, terminates at the first large pavilion, the Diwan-i-‘Am. The small black marble throne still stands over thewaterfall in the centre of the canal which flows through the building into the tank below. From time to time this garden was thrown open to the people so that they might see the Emperor enthroned in his Hall of Public Audience.

The second garden is slightly broader, consisting of two shallow terraces with the Diwan-i-Khas (the Hall of Private Audience) in the centre. The buildings have been destroyed, but their carved stone bases are left, as well as a fine platform surrounded by fountains. On the north- west boundary of this enclosure are the royal bathrooms.

At the next wall, the little guard-rooms that flank the entrance to the ladies’ garden have been rebuilt in Kashmir style on older stone bases. Here the whole effect culminates with the beautiful black marble pavilion built by Shah Jahan, which still stands in the midst of its fountain spray ; the green glitter of the water shining in the smooth, polished marble, the deep rich tone of which is repeated in the old cypress trees. Round this baradari the whole colour and perfume of the garden is concentrated, with the snows of Mahadev for a background. How well the Mughals understood the principle that the garden, like every other work of art, should have a climax.

This unique pavilion is surrounded on every side by a series of cascades, and at night when the lamps are lighted in the little arched recesses behind the shining waterfalls, it is even more fairy-like than by day. Bernier, in his account of the Shalimar, notes with astonishment four wonderful doors in this baradari. They were composed of large stones supported by pillars, taken from some of the ” Idol temples ” demolished by Shah Jahan. He also mentions several circular basins or reservoirs, ” out of which arise other fountains formed into a variety of shapes and figures.”

This unique pavilion is surrounded on every side by a series of cascades, and at night when the lamps are lighted in the little arched recesses behind the shining waterfalls, it is even more fairy-like than by day. Bernier, in his account of the Shalimar, notes with astonishment four wonderful doors in this baradari. They were composed of large stones supported by pillars, taken from some of the ” Idol temples ” demolished by Shah Jahan. He also mentions several circular basins or reservoirs, ” out of which arise other fountains formed into a variety of shapes and figures.”

When Bernier visited Kashmir the gardens were laid out in regular trellised walks and generally surrounded by the large-leafed aspen, planted at intervals of two feet. In Vigne’s time the Bagh-i-Dilawar Khan, where the European visitors were lodged, was still planted in the usual Eastern manner, with trellis -work shading the walks along the walls, ” on which were produced the finest grapes in the city.”

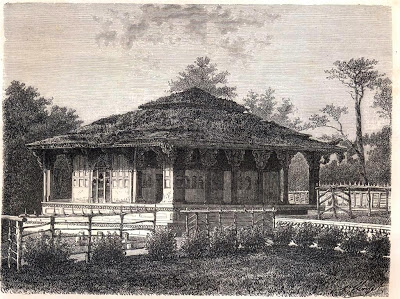

Pergolas were in all probability one of the oldest forms of garden decoration. A drawing of an ancient Egyptian pleasure-ground shows a large pergola surrounded by tanks in the centre of a square enclosure. The trellis -work takes he form of a temple with numerous columns. In the Roshanara Gardens at Delhi a broken pergola of square stone pillars still exists, and a more modern attempt has been made to build one outside the walls at Pinjor.

These cool shady alleys have, under European influence, entirely disappeared from the Kashmir gardens ; though here and there round the outer walls some of the old vines are left, coiled on the ground like huge brown water-snakes, or climbing the fast growing young poplars. But their restoration would be a simple matter. The pergolas with their brick and plaster pillars are a charming characteristic well worth reviving. It should be always remembered, however, to make them bold enough : high and wide with beds or spring bulbs on each side between the pillars spring bulbs, such as Babar’s favourite tulip and narcissus, to flower gaily before the leaves of rose and vine completely shade the walks.

These cool shady alleys have, under European influence, entirely disappeared from the Kashmir gardens ; though here and there round the outer walls some of the old vines are left, coiled on the ground like huge brown water-snakes, or climbing the fast growing young poplars. But their restoration would be a simple matter. The pergolas with their brick and plaster pillars are a charming characteristic well worth reviving. It should be always remembered, however, to make them bold enough : high and wide with beds or spring bulbs on each side between the pillars spring bulbs, such as Babar’s favourite tulip and narcissus, to flower gaily before the leaves of rose and vine completely shade the walks.

A subtle air of leisure and repose, a romantic indefinable spell, pervades the royal Shalimar : this leafy garden of dim vistas, shallow terraces, smooth sheets of falling water, and wide canals, with calm reflections broken only by the stepping-stones across the stream.

A subtle air of leisure and repose, a romantic indefinable spell, pervades the royal Shalimar : this leafy garden of dim vistas, shallow terraces, smooth sheets of falling water, and wide canals, with calm reflections broken only by the stepping-stones across the stream.

A complete contrast is offered by the Nishat, the equally beautiful garden on the Dal Lake built by Asaf Khan, Nur-Mahal’s brother.

-0-

From C.M. Villiers Stuart’s ‘Gardens of the Great Mughals’ (1913)

Read more:

Images:

1. Ground plan of Shalimar bagh found in C.M. Villiers Stuart’s ‘Gardens of the Great Mughals’

2. View from Outer Garden of Shalimar Bagh

3 Central structure at Shalimar Bagh

4. A painting of Pergola at Shalimar Bagh by H. Clerget (1870)

5. Central Pergola at Shalimar Bagh

6. Inside the central structure at Shalimar Bagh. (All photographs taken by me in June 2008)

Hello

Rizia

I love you

I know you love me

Because you Are my

1st Love & I was Damn

Sure you will be back

So

Please Speak

I Love you Since 2002

Photograph: A teenage love story on a wall of the central monument at Shalimar Garden in Srinagar, Kashmir.

June 2008.

In around 1619, Mughal Emperor Jahangir built Shalimar Garden for his beloved Iranian wife Noor Jahan.

-0-

(A Mughal Garden on the Dal Lake)

Shalimar! Shalimar!

A rythmic sound in thy name rings

A dreamy cadence from afarWithin those syllables which sings

To us of love and joyous days

Of Lalla Rukh! of pleasure feast!

Of fountains clear whose glitt’ring sprays

Drawn from the snows have never ceasedTo cast their spell on all who gaze

Upon this handiwork of love

Eeared in Jehangir’s proudest daysHomage for Nur Mahal to prove.

For his fair Queen he built these courts

With porphyry pillars smooth and blackWhose grandeur still expresses thoughts

For her that should no beauty lack.The roses show ‘ring o’er these walls

Still fondly whisper love lurks hereAnd still he beckoning to us calls

By yon Dai’s shores in fair Kashmir.

~ Muriel A.E. Brown

Chenar Leaves: Poems of Kashmir (1921)

Mrs. Percy Brown

Published by Longmans,Green and Co (London) in 1921.

-0-

Photograph taken by me in June 2008

Photograph taken by me in June 2008

Muriel Agnes Eleanora Talbot Brown dedicated the collection of verses to the memory of her father, the late Lt.-Col. Sir Adelbert Cecil Talbot ( b. 3 June 1845, d. 28 December 1920) who was the Resident of Kashmir from 1896 to 1900. Earlier he had also been the Chief political resident of the Arabian (Persian) Gulf (for Bahrain, Bushire, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, and the Trucial States) from 1891 to 1893.

Muriel Agnes Eleanora Talbot was married to Percy Brown, art historian famous for his work on History of Indian architecture ( Buddhist and Hindu, 1942 ). Percy Brown was at one time the Principal of Mayo School of Art, Lahore and curator of the Lahore Museum.He also served the post of principal of Government School of Art and Craft, Calcutta and Curator of the Government Art Gallery Calcutta. In his later years, he settled in Kashmir and was instrumental in guiding some local Kashmiri painters, musician and other artists. He died on 22 March 1955 in Srinagar, Kashmir, India.

-0-

Read this for history of Mughal Gardens of Kashmir

Get the complete set of poems from Chenar Leaves: Poems of Kashmir at Archive.org