“These terracotta plaques at Harwan each of which was

moulded with a design in bas-relief, are of a character which makes them unique

in Indian art. Pressed out of moulds so that the same pattern is frequently repeated, although spirited and naive in some instances, they are not highly

finished productions, but their value lies in the fact that they represent

motifs suggestive of more than half a dozen alien civilizations of the ancient

world, besides others which are indigenous and local. Such are the Bahraut railing,

the Greek swan, the Sasanian foliated bird, the Persian vase, the Roman rosette,

the Chinese fret, the Indian elephant, the Assyrian lion, with figures of

dancers, musicians, cavaliers and ascetics, and racial types from many sources,

as may be seen by their costumes and accessories.”

~ Percy Brown, Indian Architecture: Buddhist and Hindu

periods (1942)

Aurel Stein in his edition (1892) of Kalhana’s Rajatarangini identified terraced site of Harwan as Sadarhadvana, ‘The wood of six saints’, the place where once lived the famous Bodhisattva Nagarjuna of Kushan period in the time of King Kanishka. The site was first excavated in year 1923 by Pandit Ram Chandra Kak. Based on masonry styles Kak categorical the structures and findings into three types: (i) Pebble style (ii) Diapher Pebble style, and (iii) Diapher Rubble style. The pebble style being earliest in date, the diapher pebble of about 300 A.D. and the last one of about 500 A.D. and later.

Here are some of the photographs of the tiles of Harwan ( Harichandrun, originally in Kashmir) provide by Kak (

came across in booklet ‘Early Terracotta Art of Kashmir’ by Aijaz A. Bandey for Centre of Central Asian Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar (1992)):

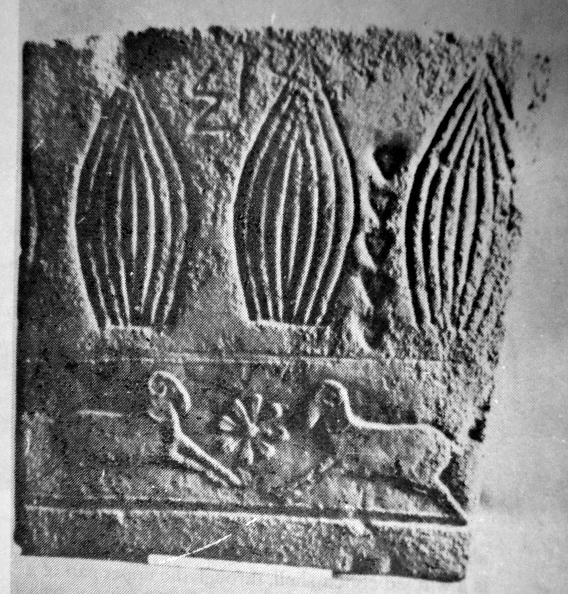

First one, a tile that gave me an opportunity to interpret a symbol.

|

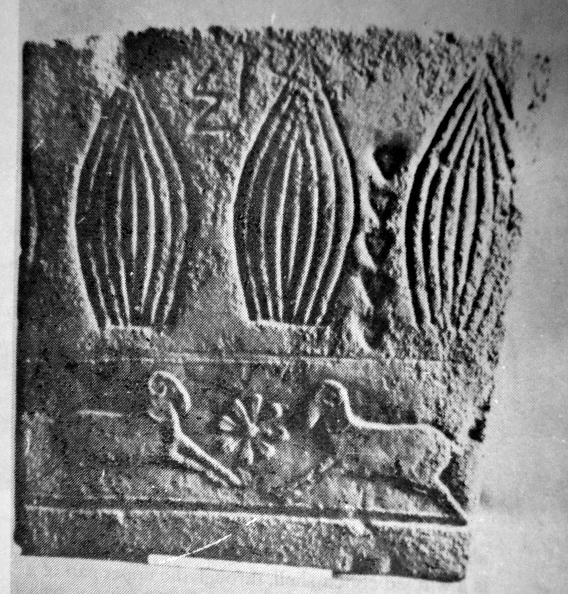

| Here above are shown four full blown lotus flowers; below a procession of geese running with their wings open. It is to be noted here the four geese from left have already picked up a stalked flower in their bills while the extreme right bird is about to pick it up. This males the scene more alive. |

The point here is that it is not just an ‘alive scene’, it is an animated scene, there are no four, five geese, there is only one goose, the way the scene is set, it looks like an “animation cel;”, it is as if the artist was not trying to capture just the subject but also motion, hence we have an animated scene of a geese in motion, catching, leaving, holding on to a flower.

Why geese? What does this motion symbolize?

Goose in Indian motifs (both in Buddhist, to a great degree also in Hindu art and lore ) is the most common and recurring symbol of an ascetic in search of truth. In art, geese with a flower in beak would be the state of perfection, and the flight would be the journey that an ascetic undertakes. And then in addition, there is this impression of “passing” time that the flight symbolizes. It is a simple and obvious explanation.

In fact, it must have occurred to some other observers too. In ‘The Goose in Indian Literature and Art’ (1962), Jean Philippe Vogel cautions against such a tempting answer easily. “It is tempting to assume a connection between the yogis and the geese, although the latter appear also on tiles belonging to the courtyard where they seem to have a merely decorative function.”

Can’t a religious symbol be used in a secular space with a decorative function? But then, that would be akin to how in present times say a ‘Ganesha’ statue might be found in a corner of drawing room of a Hindu household, performing a decorative and a religious function. Is is difficult to assume that people back then too were capable of doing something like this.

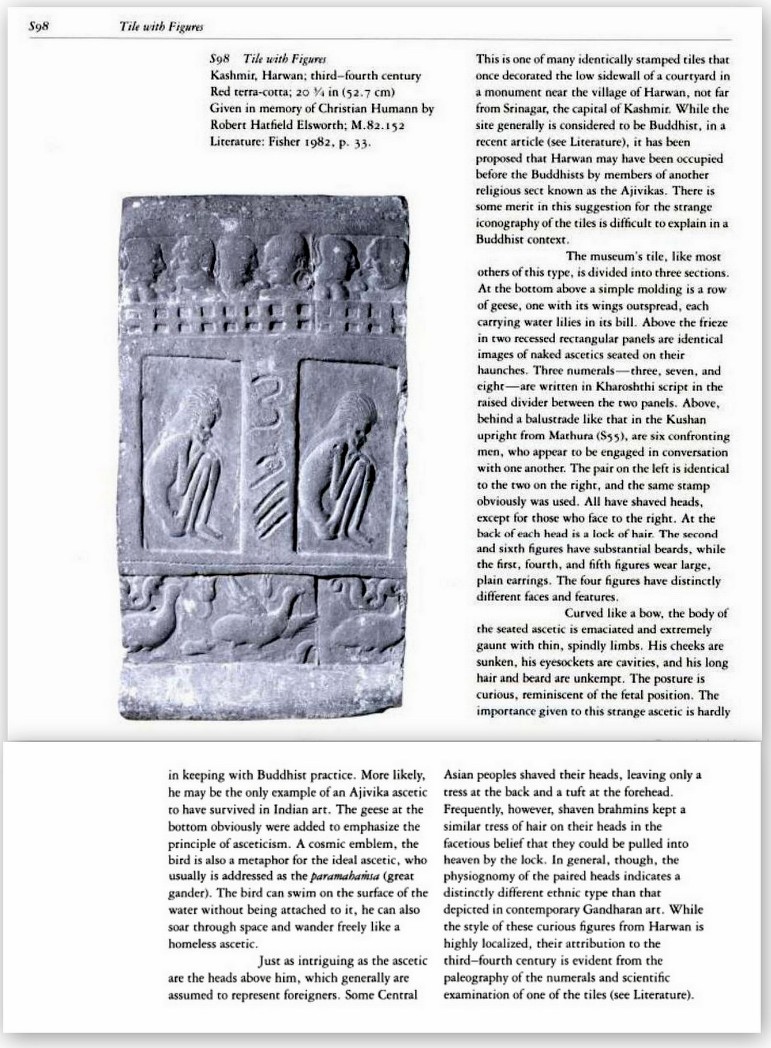

Dating back to third and the fifth century, Harwan is not an easy site to decipher. Each symbol is capable of throwing interesting questions at the observer. Take the case of ascetics. When we see ascetics in these tiles, are we seeing Buddhist ascetics? Although Harwan is often thought as a Buddhist site, there are theories according to which the Buddhist site was built on top of an existing site claimed by a religious sect called

Ajaivika belonging to Nastika thought system. The sect peaked at the time of Mauryan emperor Bindusara around the 4th century BC. But by the time of Ashoka the sect quickly went downhill (apparently, the fact they published a photograph of Buddha in negative light didn’t go well with Ashoka the Great and he had around 18000 followers of the sect executed in Pundravardhana, present day Bengal). The sect disappeared without leaving much trace.

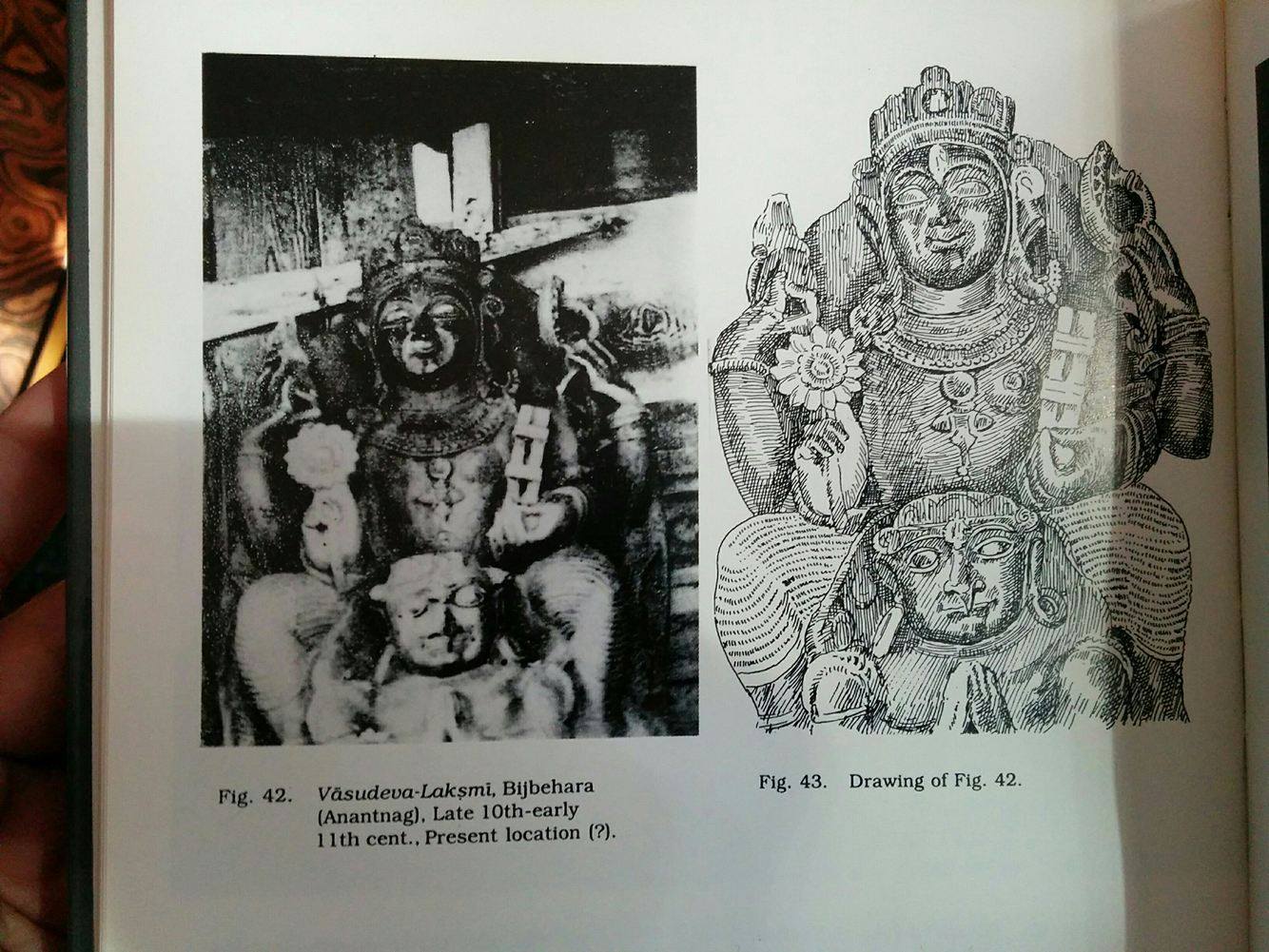

However, it is interesting the only image of an Ajaivika ascetic may have been provided by Kashmir. Below is given a page from ‘Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700’ by Pratapaditya Pal.

Some other tiles from Harwan (a site that was almost lost again and buried after a cloud burst in 1970s):

|

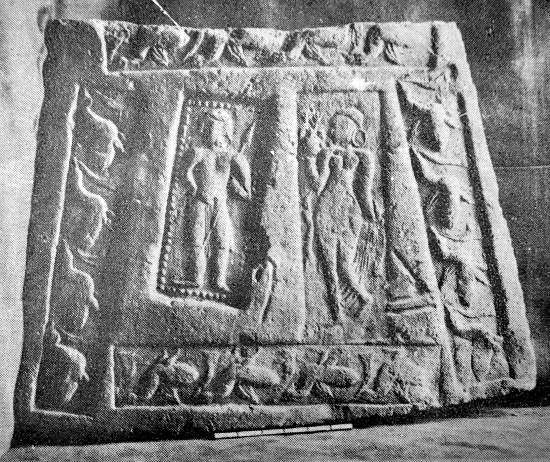

| A female holding a flower vase in upright hand, the left hand lifts the end of transparent long robe. The woman on either side has lotus petals, below in a separate register is a procession of four geese. The marked difference, this tile from harwan displays, is in its shape which is unconventional but could have fitted in the pavement plan at the site. |

|

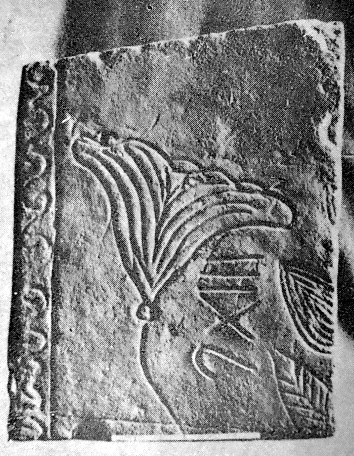

| Medallions contaning cocks, regardant, with stylized foliate tails. Below in running spiral in an unending whorl. |

|

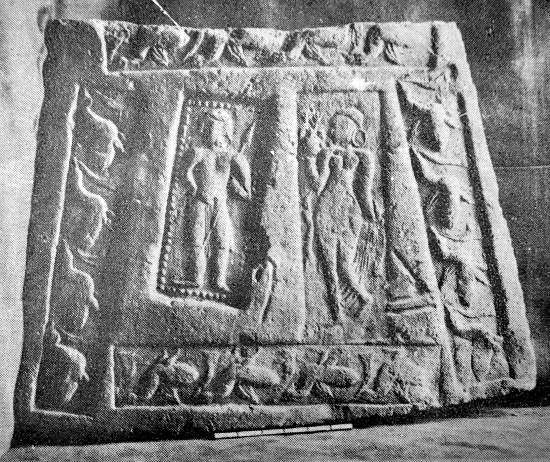

| A squarish tile has in the centre two seperate stamps, the left one in a dotted boarder a standing male figure with splayed out feet, a long tunic extending upto knees, holding in the left hand a long spear, while the right rests on the lip. All along the border of the tile on each side is a procession of four geese. |

|

| A female holding flower vase, a male holding spear, medallion with cock, and procession of geese. |

|

| In the left a deer looking back, with moon at the top and wheel below. right, a mounted archer “The Parthian shot” of ancient Iran. |

|

| Upper register, a couple in a balcony. The coarse features of the couple having high cheek-bones, prominent noses and low receding fore head, allowed thr excavator (R.C. Kak) to identify them with a racial group of Central Asian people. Below, a feeling deer who is just to be struck with an arrow. |

|

| A composite mortified tile from Harwan. the tile above has lotus flowers; below in one compartment is a winged conch-shell, through the upper part of it protrudes neck of a bird (?) emitting pearl. This composite creature is flanked on either side by a fish at the bottom. To its right in a separate compartment is another composite figure, in this case half human and half vegetal; the upper part is of a female bust. |

|

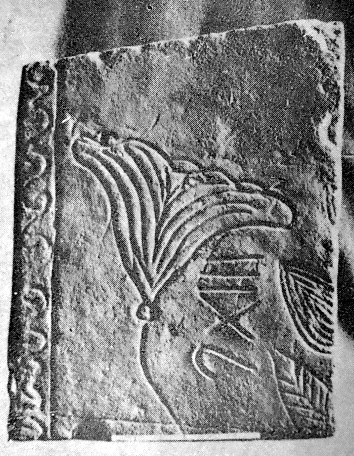

| Three lotus petals and two rams. |

|

| Two cocks fighting over a lotus bud. Two deers at night. |

|

| Medallions with cocks with grape vines scroll above and below |

|

| Mixing of motifs. Cock, Lotus, Geese, |

|

| Lotus |

|

| unconventional. A free hand drawing of a flower. |

-0-

“

“