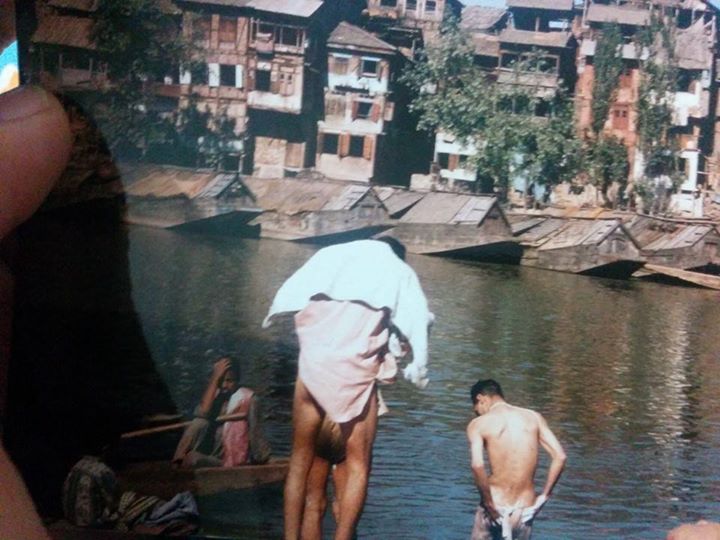

Vishav, in flood, has overflown her banks.

When I was a child, wherever I would spill a glass of water, the exclamation from my mother or grandmother would be, ‘Ye kus Sylaab!’ (What’s this flood!). The house I was born in Chattabal was near a river. The hundred year old wooden house was built a good three feet above the ground. As a child I never understood the real need for it. I was told it was for safety from the floods. I would wonder: ‘What floods?’. I had seen the quite river. No way was that river ever going to reach our doorstep and then climb these three feet too. Then in autumn of 1988 (or was it 1989?), I remember, one morning, on way to the house of the gourbai (milkmaid), walking to the small foot bridge over the river and finding planted at the start of it a red skull and bone signboard with ‘Danger’ written across it. The reading at Sangam wasn’t good. A flood warning had been issued in Kashmir. I waited for water to rise. Would we be using boats in the house. Could I fish? I waited. The flood never arrived at the gate.

2082-2041 B.C.

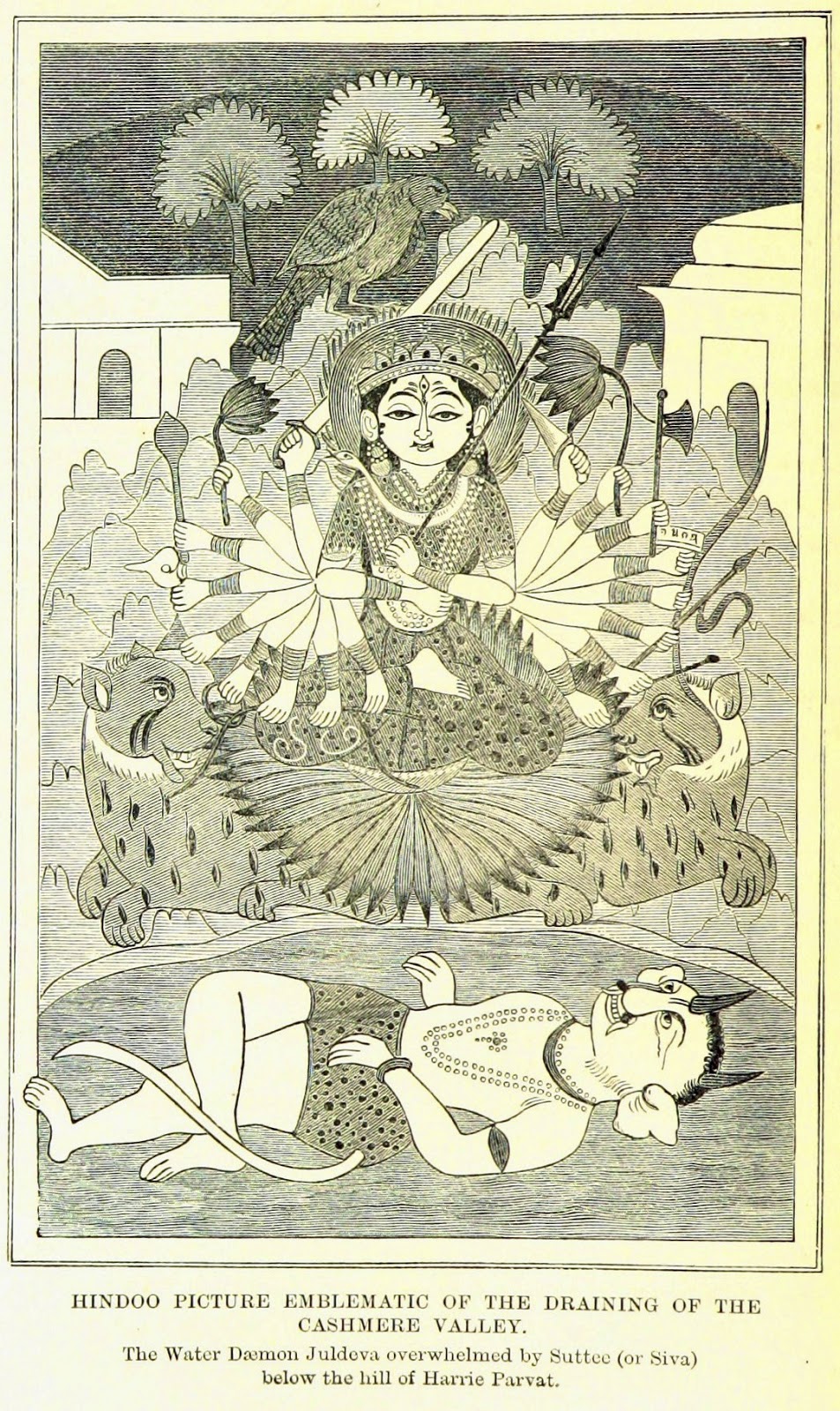

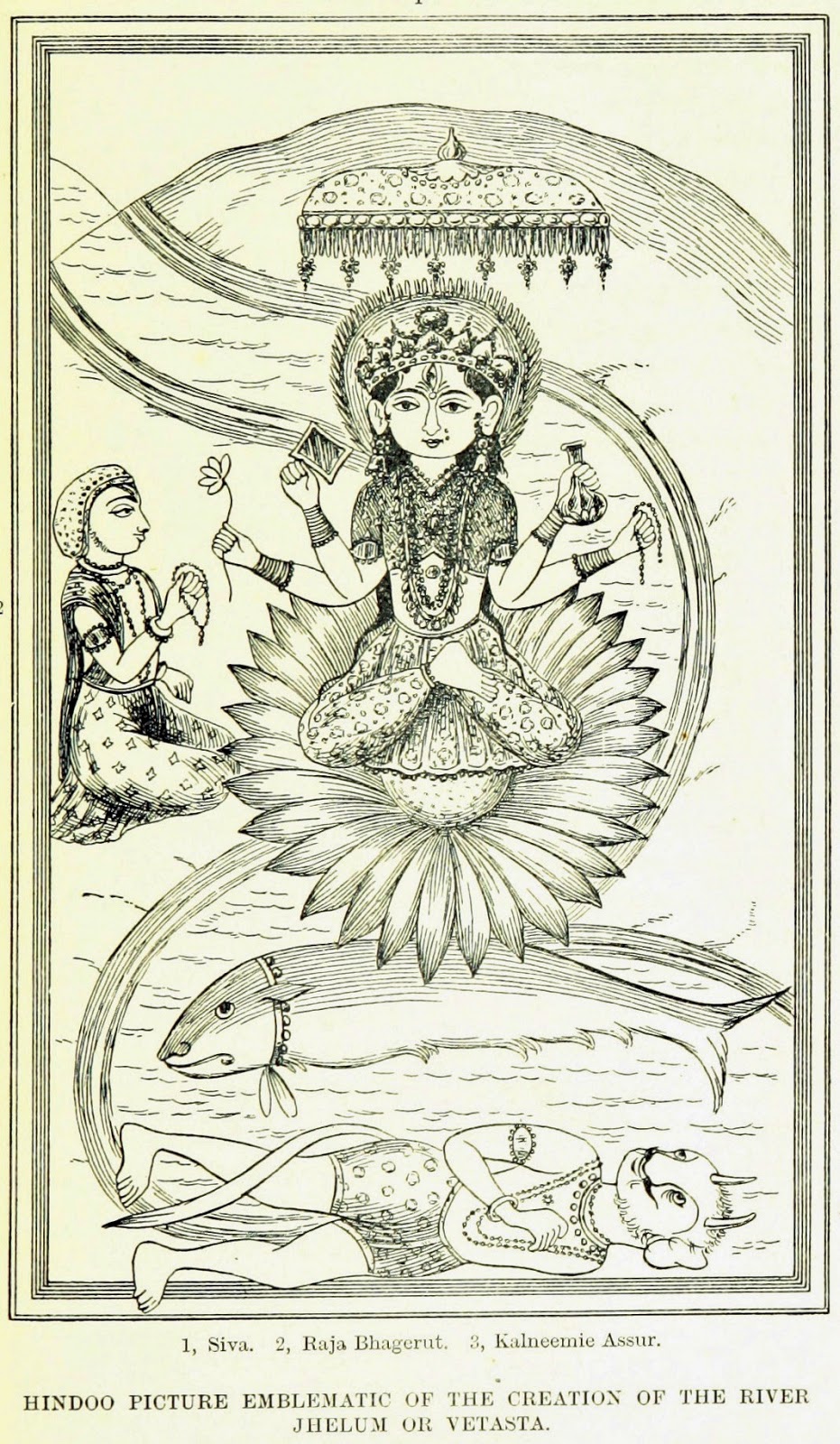

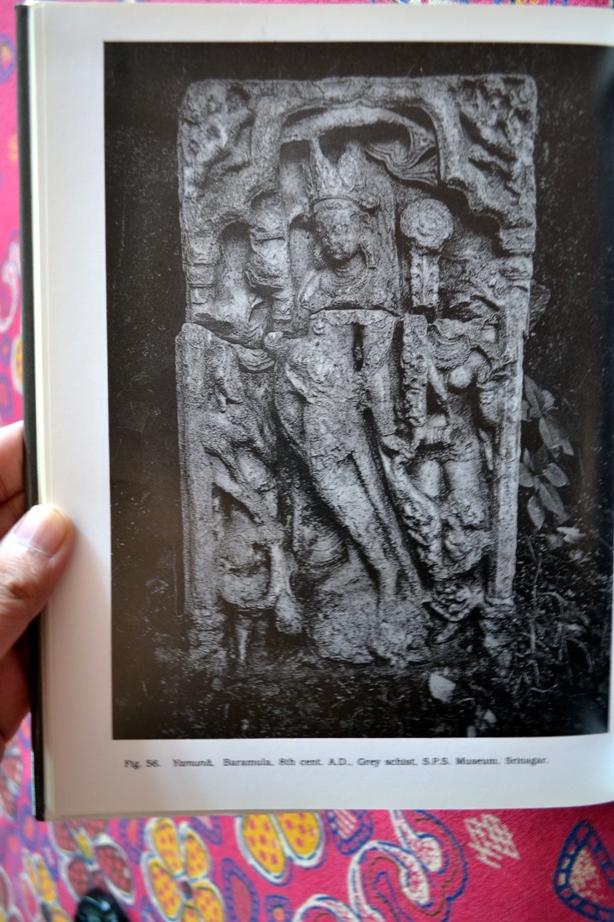

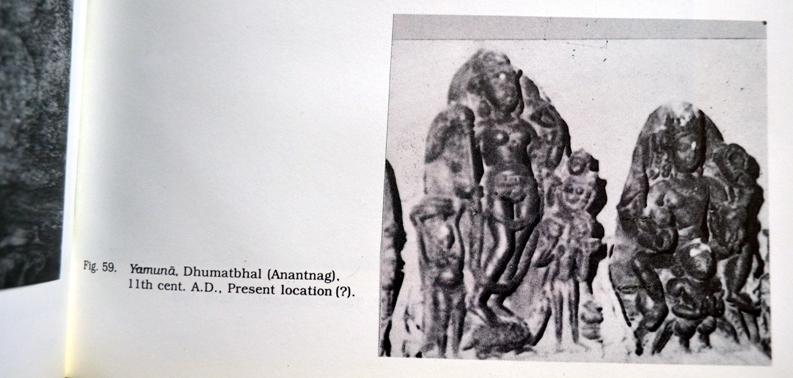

The one story about Wular from legends. In the time of Sundar Sena, a destructive earthquake occurred by which the earth in the middle of the city of Sandimatnagar was rift and water gushed out in a flood [from Ular Nag] and soon submerged the whole city. By the same earthquake a knoll of the hill at Baramulla near Khandanyar tumbled down which chocked the outlet of the river Jhelum and consequently the water rose high at once and drowned the whole city together with its king and inhabitants. This submerged city is now the site occupied by the Vular Lake.*

* 635 A.D.

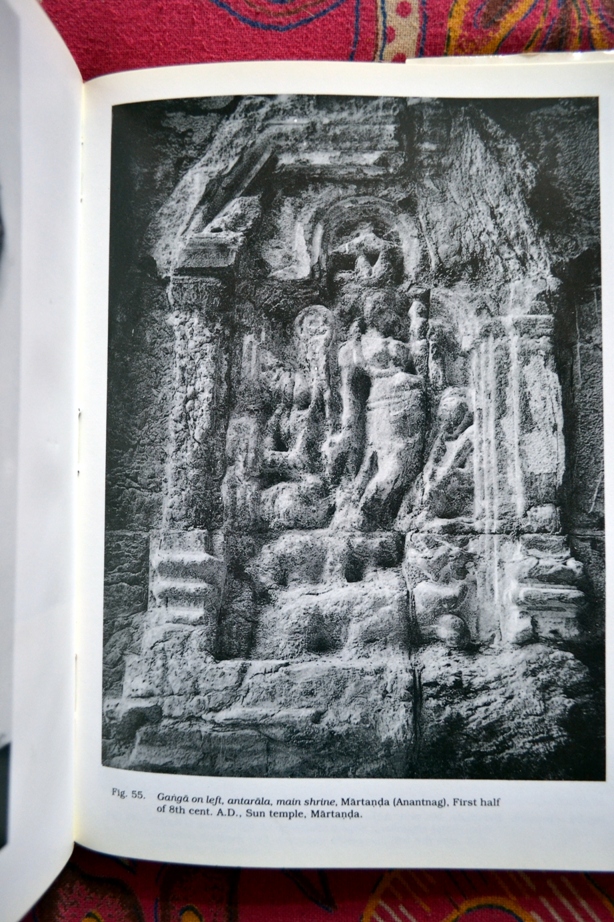

During the reign of Raja Durlab Duran, the city of Srinagar was drowned due to a heavy rainfall and the dam (Sadd) at Talan Marg built by Raja Parvaesen, were destroyed. As a result of Talan Marg being flooded, the Dal lake was formed.

724-761 A.D.

During the reign og Laltaditya due to a flood, all buildingd of the Raja in the town were destroyed. So, he rebuilt his palace in Litapur.

855-882 A.D

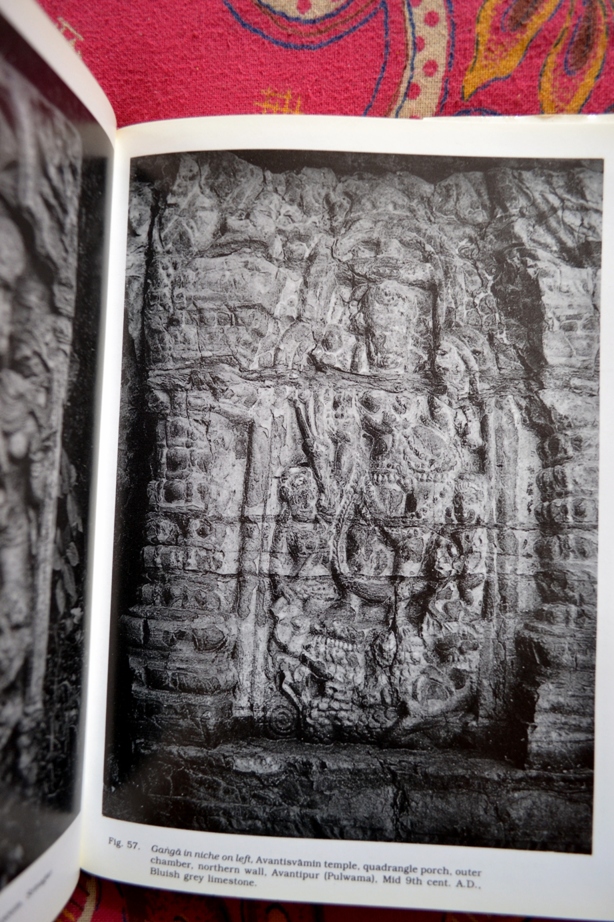

During the time of Avantivarman, famine was caused by flood and then steps were taken to deepen the Jhelum near Khadanyar in order to accelerate the flow of the river. This measure had the effect of minimising the chances of flood as it was concluded that flooding has happened because of blocking of a river pass at Khadniyar.

917-8 A.D.

During the time of King Partha, rive crop was destroyed by flood, the result being a great famine. Srinagar drowned as houses floated on the river as though they were bubbles. *

1122 A.D.

During the time of Harsha, crops were swept away.

1379 A.D.

During the time of Sultan Shahabud-Din, 10000 houses were destroyed

[The above entry is by Anand Koul. And probably wrong on account of timeline [the Sulatan died in 1373]. Also, Rajatarangini of Jonaraja tells us:

There was flood in 1361. The town of Laxmi-Nagar was founded at Hari Parbat by Sultan Shahabud-Din to rehabilitate the people of the Srinagar city.It was named after his wife Laxmi. ]

1573 A.D.

Ali Khan Chak’s time many houses and crops were swept away*

1662 A.D.

Houses destroyed during Ibrahim Khan’s rule. According to Hassan the year was 1682 A.D. and the reason was a severe storm in which houses whirled around on water like boats. At the time an earthquake is also supposed to have occurred.

1730 A.D.

Houses and crops destroyed during Nawazish Khan’s time due to heavy rains.*

1735 A.D.

Thousands of houses said to be destroyed during Dildiler Khan’s time. * After eight days of rain, flood water stayed in courtyards of houses as well as in the fields for a long time.

1746 A.D.

10,000 house and all the bridges on the Jhelum and also the crops swept away during time time of Afrasiab Khan.*

1770 A.D.

All bridges and many houses destroyed during Amir Khan Jawansher’s time.*

1787 A.D.

During Juma Khan’s time, Dal Gate [*Qazi Zadeh] gave way and all the easter portion of the city of Srinagar was submerged.*

1787 A.D.

Crops destroyed during Abdullah Khan’s time*

1836 A.D.

Bridges at Khanabal, Bijbihara. Pampor and Amira Kadal were swept away during the time of Col. Mian Singh.*

1841 A.D.

During the time of Shekh Gulam Mohiuddin, rain fell for seven days continually, Jhelum overflowed the Dal Bund [ Qazi Zadeh] and submerged the whole Khanyar and Rainawari. Six bridges from Fateh Kadal to Sumbal were swept away. *

[1844. great Gilgit valley flood ]

[*1882 A.D.

Sind-lar river flooded, changed course, water entered Anchar Lake extending the size of the lake three times. (Before this flooding, Anchar Lake was much smaller (probably of the present size)]

[‘John Bishop Memorial Hospital’ got washed away in devastating floods of 1892.~ Until the shadows flee away the story of C.E.Z.M.S. work in India and Ceylon (1912)]

21st July 1893

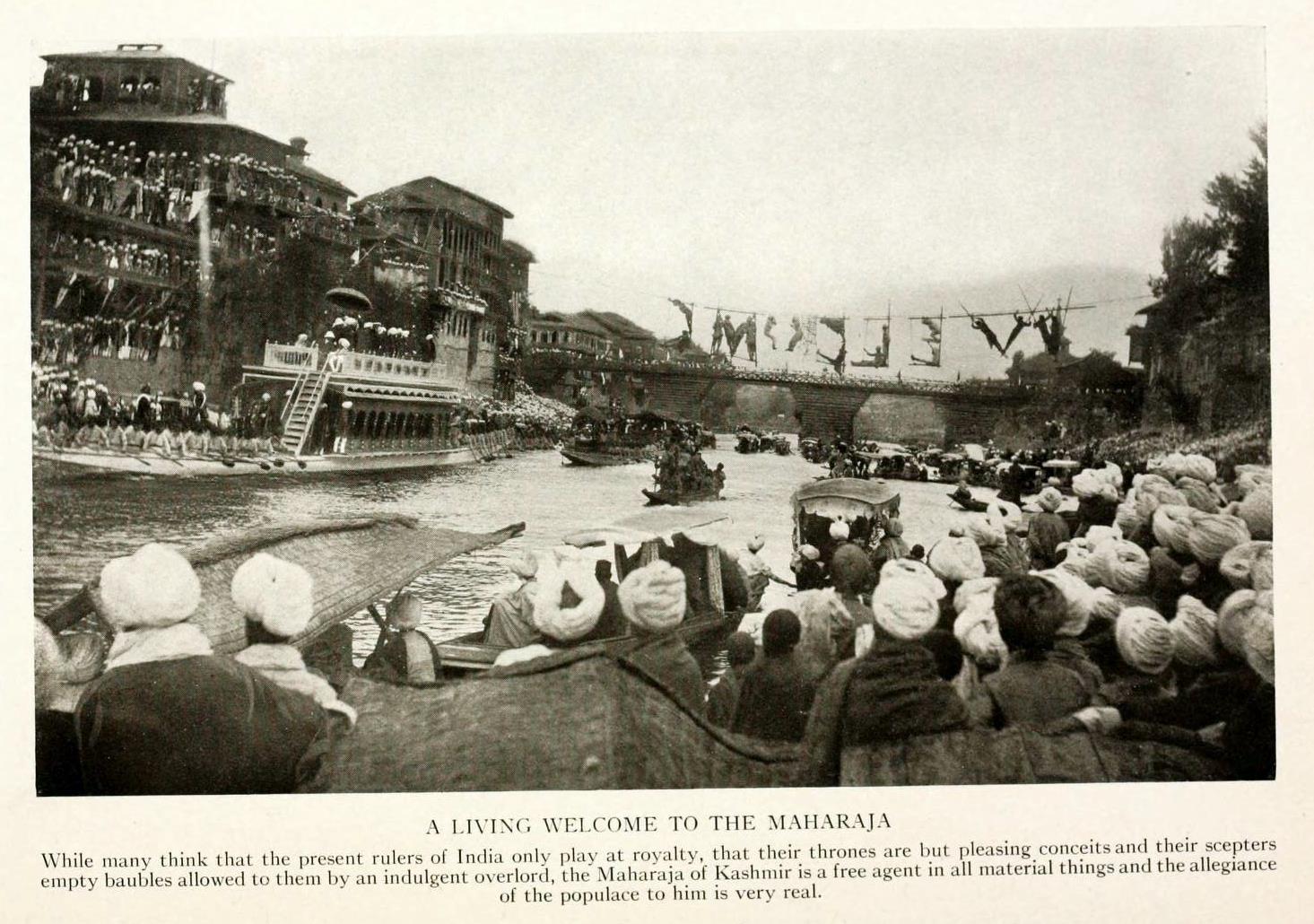

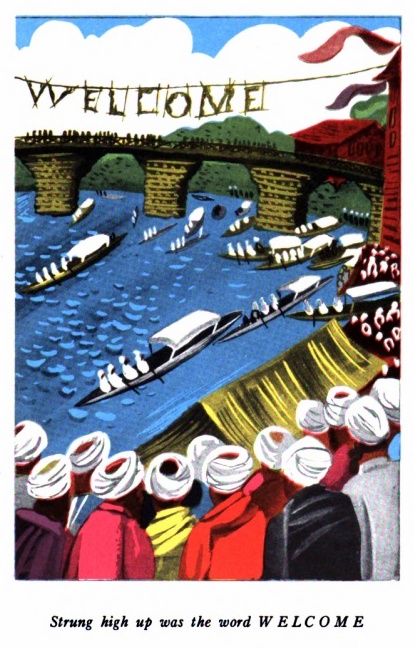

The first of the well documented case of flooding in Kashmir during the time of Maharaja Pratap Singh. It rained incessantly for 59 hours and the river became so swollen that miles of land on both banks were flooded. The water rose to the height of R.L. 5197.0. All the bridges except Amira Kadal, and many houses were destroyed. Loss of cattle and crops was immense and many people were drowned. A detailed account of this and previous flood was provided by Walter Lawrence in his ‘Valley of Kashmir’ (1895).

“In 1841, there was a major flood which caused much damage to the life and property in Srinagar. Some marks shown to me suggest that the flood of 1841 rose some nine feet higher on the Dal lake than it rose in 1893. But thanks to the strong embankments around Dal, the flood level in 1893 never rose on the lane to the level of the flood in Jhelum”

It is interesting to note that New town area of Srinagar was formed in 1891, in the 1893 flood most of the old town of Srinagar was swept. After the flood of 1893, Jhelum bank was strengthened to protect Munshi Bagh, and the new ‘bund’ came up. This was the first of ‘Great Flood’ in recent history after which modern preventive measures were started.

Between 1895 and 1903, flood kept arriving.

1900

The water was nine feet lower at Munshibagh than its predecessor. It is chiefly remembered for the breaches in the right bank above Shergrahi.

1902

The flood of 1902 was lower than the previous one by 2’2 feet.

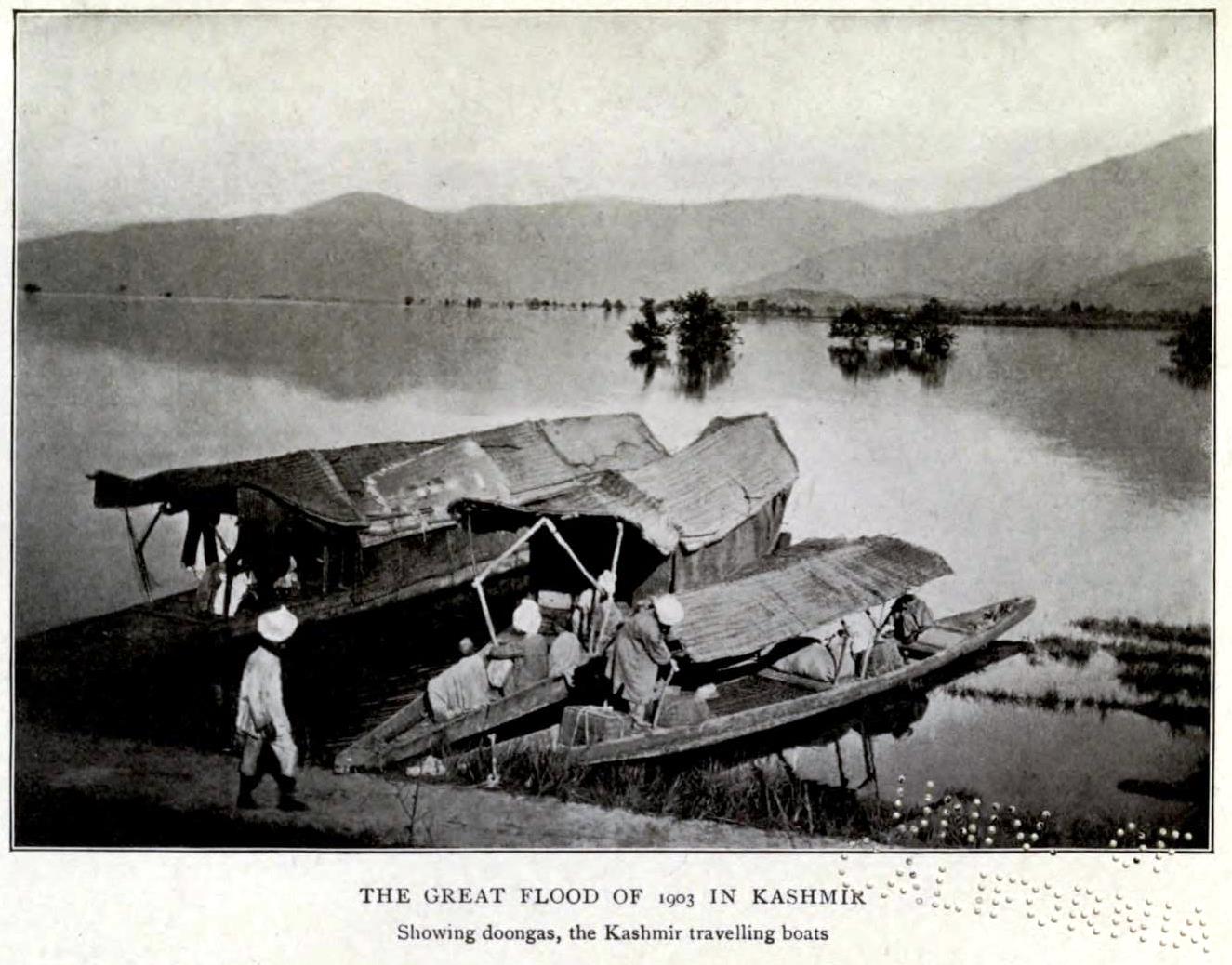

24th July 1903

The second of the great flooding in modern times. Five inches of rain fell between 11th and 17th July and eight inches from 21st to 23rd idem and the river rose to the maximum of R.L. 5200.37 on the 24th July at 2 P.M. The whole valley became one vast expanse of water and fearful loss of life and property and crops occurred. The damages caused to the roads and other Public works alone rose to over three lakhs of rupees.

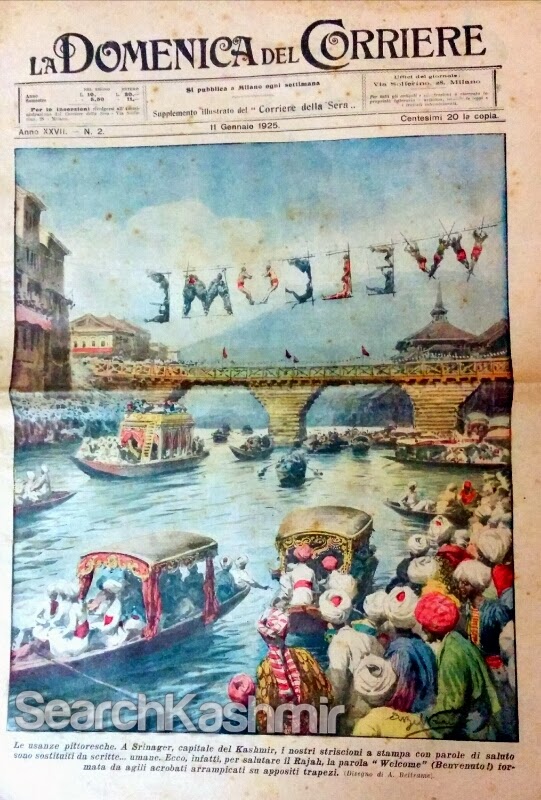

V.C. Scott O’connor mentions that people claimed Dal Lake rose Ten feet in thirty minutes. Three thousand houses in and around Sringar collapsed, and over forty miles of roads were under water.

This was the flood that lead to the first proper scientific approach to control the floods in the valley using the help of British. In 1904, a spill channel was excavated above Srinagar through a swamp rejoining the river at some distance below the city and proved much helpful in protecting Srinagar. Dredging work started in 1907 from Baramulla unto Vular Lake using electricity. In around 1906, came the weir at Chattabal. The flood control work with British help continued for a couple of decades. A Kashmiri poet of that time named Hakim Habibullah went on to write a work titled ‘Sylab Nama’ based on this natural calamity of 1903.

The flood kept arriving at regular interval: 1905, 1909, 1912, 1918, 1926, 1928 (about 75 people lost lives), 1929, 1932, 1948.

During the years 1900 and 1965, valley experienced about 15 major floods.

1950

Fifties started with flood. In 1950, water of Jhleum was flowing 10-15 feet over the banks in Srinagar. In all about 70 mile area of the valley was under water. In Jammu, about 12,000 houses collapsed.

In the fifties, the floods were witnessed in: 1950, 1951, 1953, 1954, 1956, 1957 and 1959. Of these, the floods in 1950, 1954, 1957 and 1959 were major. And among them the flood of 1957 and 1959 were two greatest ever in recent recorded times of Kashmir.

1957

Capacity of Jhelum river is 36,000 to 50,000 cusecs and flood situation is declared in Kashmir when the water discharge at Sangam in south Kashmir is above 24 thousand cusecs.

In 1957 it was estimated roughly to be 90,000 cusecs to 1 lakh 20 thousand cusecs at Sangam while the flood capacity of Jhelum is 90,000 cusecs. That year Wular Lake rose from normal height of 5,172 meters to 5,184 meters. It is said, “the area on the left bank of the Jhelum from Sangam to Srinagar, and on the right bank from Sangam to Barsoo, appeared one continues sheet of water, with the submerged village site sticking out as bench marks on the watery waste.” Human lives lost were at about 41 with 600 villages inundated. The damages was at about Rs 4.2 crores.

July, 1959

This flood is considered the most devastating in recent times. Jhelum was assumed to be at 80,000 cusecs to 100,000 against its normal capacity of 17,000 cusecs. The highest gauge touched at Sangam was 31.00 feets and the discharge through the river was about 50,000 cusecs.

About 82 people lost lives. Damage to public utility services was about Rs. 20 million, in addition to Rs. 15.6 million of damage to crops.

1960s started with Kashmir placing order for British shovels and two American dredgers (costing about $16, 800,00 or 8 Crore of the time) capable of dredging 750 cubic feet per hour. The floods continued in 1962, 1963, 1964, 1969 and 1972.

August 1973

About 20% of the population of the state impacted flooding about 40 villages. About seventy people dead, with 50 in Jammu province and about 21 of drowning in Kashmir. Damages amounted to Rs 12.18 crores. The Buddhist site at Harwan (the upper terrace) was buried under debris during this flood (it was finally cleared in 1978-80).

Floods kept arriving at regular intervals

1976

1986

1988

14,700 hectares of land was under water, 1.66 lakh quintal of paddy crop costing Rs. 2.50 crore were damaged. Three hundred villages were affected and four hundred and fifty hours were washed away. Loss of irrigation and flood-control works totalled Rs 15.50 crore.

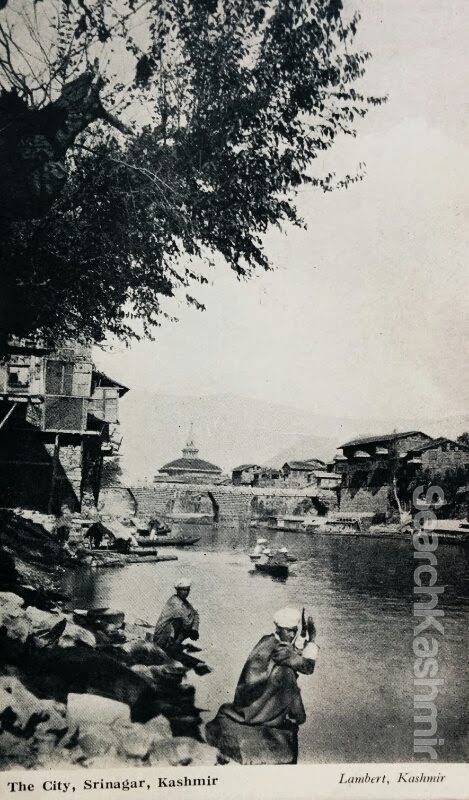

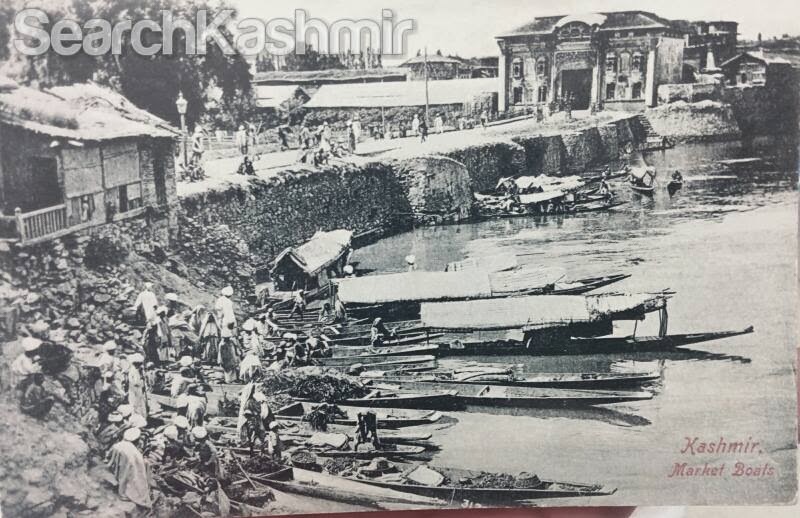

The possible reason for damage to the city from these recent floods remains the slitting of water bodies. “The 1891 census of the state mentions 34,000 boatmen using the Jhelum as the Kashmir Valley’s only highway. Today Jhelum is least fit to accommodate even an average sized cargo boat. So shallow are the waters that in the summer of 1987 one could wade through the river as it passed through Srinagar.”

September 1992

About 210 lives lost.

1995

August 1996

Happened while Amarnath Yatra was going on, about 160 dead.

2010

September, 2014

Triggered by merging of western disturbance and the monsoon over the entire three regions of the State. Heavy rain experienced in upper reaches of Kashmir on 2nd, 3rd and 4th. Upper-reaches of Pahalgam experience three massive cloudbursts.

On 3rd September, Gauge at Sangam reads 21 feet. Flood is normally declared when water is at 23 feet. Ram Munshi bagh reading is 12 feet. Danger mark is 18 feet. People worry about the rising water levels. Rains continue.

On Sept 07, 2014. Flood hits Srinagar city. Deaths in Jammu regions.

Gauge reading at around 1200 hrs in Srinagar:

Sangam = Gauge plate under water (last recorded gauge 33.65 ft).

Ram Munshibagh = Gauge plate under water (last recorded gauge 26.25 ft).

Ashram = 17.58 ft

Conditions abate by September 10th. But almost entire Srinagar under water.

|

| Satellite image of Srinagar as on 10th September |

-0-