In 1863,

Samuel Bourne, a British photographer during his work trip to Kashmir was having trouble trying to get a troupe of Kashmiri dancing girls to pose for a photograph. After successfully taking a satisfactory photograph, much later, in his

Narrative of a photographic trip to Kashmir (Cashmere) and adjacent territories (

British Journal of Photography, 25 January 1867), he recounted:

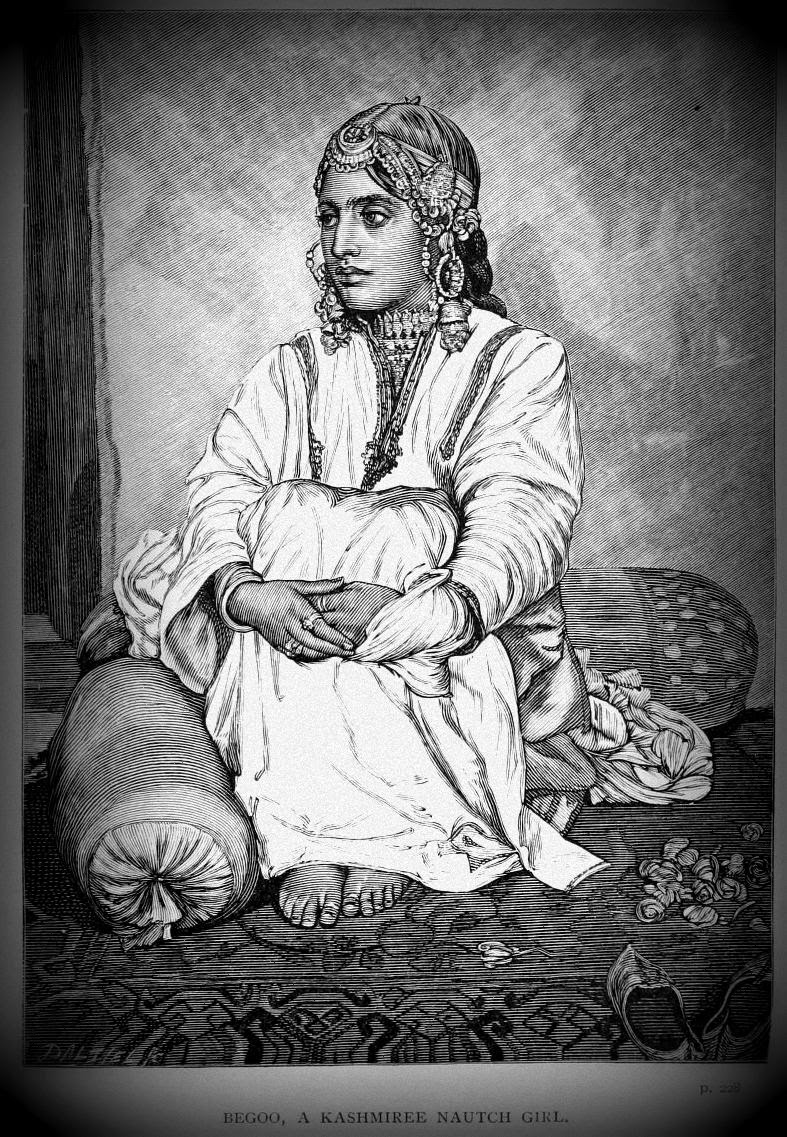

“By no amount of talking and acting could I get them to stand or sit in an easy, natural attitude . . . The English Commissioner resident at Srinnugur (Srinagar). . . gave an order to have a number of the best-looking girls collected, of whom I was to take a group. They were very shy at making their appearance in daylight, as, like the owl, they are birds of night. They came decked out in all their rings and jewelery. and all their silk holiday attire; but, on taking a cursory glance at them when they were all assembled, with the exception of two or three, one could not help coming to the conclusion that if these were the prettiest, the rest must be miserably ugly. Much to my annoyance, a number of gentlemen had assembled ‘to see the fun’, and their presence by no means added to the composure of my fair sitters. They squatted themselves down on the carpet which had been provided for them, and absolutely refused to move an inch for any purpose of posing; so, after trying in vain to get them into something like order, was obliged to take them as they were, the picture, of course, being far from a good one . . . (13) (plate 22).”

He also explains why the ‘fair’ Kashmiris appeared dark in photographs:

“A photograph hardly does justice to native beauty; the fair olive complexion comes out much darker than it appears to the eye, on account of its being a partially non-actinic colour.”

A couple of years later, these dancing girls seem to have posed happily for a photographer named John Burke. Azeezie, probably a popular dancing girl at time in Kashmir, posed no less than four times for him. Burke, in notes to these photographs mentions some other dancing girls named Sabie and Mokhtarjan. In fact, all three of them had earlier been photographed by Bourne. Around the same time, another visitor to Kashmir, Captain William Henry Knight in his Diary of a Pedestrian in Cashmere and Thibet (1863) mentions a Kashmiri dancing girl named Gulabie. These dancing girls had already been made famous by the western travelers through their travel writings and were given the misnomer of nach/nauch/nautch girls.

As opposed to the first euphoric description of Kashmiri Beauty by Bernier, the new western travelers to the valley were trying to write a more reasonable and realistic account of Kashmiri beauty. Naturally, not all the nautch girls came out looking pretty in these accounts. In their accounts, these travelers noted that most of these dancing girls worked at Shalimar Bagh that was built by the Mughals. Here, lamps were lit at night and camps were set in the garden. And the tourists often used to visit these camps. Pran Nevile, a man who knows much about the history of nautch girls of India and author of the book Stories from the Raj: Sahibs, Memsahibs and Others,writes:

“There is a fascinating description by Lieutenant Colonel Tarrens (1860) of a nautch by Kashmiri girls in the Shalimar Gardens at Srinagar. The author was enchanted by the beauty of Shalimar, the queen of gardens, which he felt should be visited at night by the pale of moonlight when it is properly bedecked with torches, and crowned with lamps. Then “the proper thing to do is to give orders for a nautch at Shalimar.” Apart from the beauty of the place, Torrens was enchanted with the dancing and singing of the charming Kashmiri nautch girls whom he considered “vastly superior” to what he had seen elsewhere. Another witness to a similar performance in Shalimar Gardens was a reputed professional artist, William Simpson, who was so much enthralled by the sight of nautch girls dancing by torchlight that he describes it as “the sweet delusion of a never to be forgotten night.”

Often, in these accounts, they also noticed that Kashmir must once have been a great country but with years of cruel Pathan rule – it was in a state of slow decay.

Godfrey Thomas Vigne in his excellent book Travels in Kashmir, Ladak, Iskardo (1844) * wrote about a remote Kashmiri village that was once renowned for producing the best dancing girls. On his visit to Kashmir in 1835, he wrote :

“The village of Changus,** but a few miles from Achibul, was celebrated in times gone by as containing a colony of dancing girls, whose singing and dancing were more celebrated than those of any other part of the valley. I have heard Samud Shah and other old men breathe forth signs of regret, and expressions of admiration, when speaking of days that were past; and the grace and beauty of one of the Changus’ danseuses, whose name was, I think, Lyli, and long since dead, seemed to be quite fresh in their recollection. The village itself, like every thing else in Kashmir, has fallen to decay. A few of the votaries of Terpsichore still remain, but are inferior in beauty and accomplishments to those in the city, and continue to get a living by what would technically called provincial engagements. From one of them, whom I heard singing, I picked up the following air, which I believe to be original, although the first line bears, it cannot be denied, a striking resemblance to that of Liston’s “Kitty Clover.” Of word I know nothing, excepting that they were, as usual, of amorous import.”

And in the next two pages of the book, he gave the actual notes of the song (here’s a recreation of that old melody). These travelogues were read all around the world and easily seeped in works like History of prostitution: its extent, causes, and effects throughout the world by one William W. Sanger, published in 1859. The author, mocking Easter depravity and amoral lifestyle, wrote:

“Unoppressed by any rigid code of etiquette, and naturally addicted to pleasure, the people of Kashmir find much of their enjoyment in female society, and from the earliest times have been noted for their love of singers and dancers. In former days the capital city was the scene of constant revels, in which morality was but but a secondary consideration, and now the inhabitants relieve the continual struggle against misfortune and despotism by indulging in gross vices, and drown the sense of hopeless poverty in the gratification of animal passions. The women of this delightful valley have long been celebrated for their beauty, and are still called the flower of the Oriental race. The face is of a dark complexion, richly flushed with pink; the eyes large, almond-shaped, and overflowing with a peculiar liquid brilliance; the features regular, harmonious, and fine; the limbs and bodies are models of grace. But all writers agree that art does nothing to aid nature, and it is not unusual to see eyes unsurpassed for brightness and expression flashing from a very dirty face. Among the poorer classes filth and degradation render many women actually repulsive, notwithstanding their resplendent beauty.

Travelers always remark the dancing girls who have acquired much renown in Kashmir. The village of Changus was at one time celebrated for a colony of these women, who excelled all others in the valley; but now its famous beauties have disappeared, and live only in the traditions of the place. The dancing girls may be divided into several classes. Among the higher may be found those who are virtuous and modest, probably to about the same extent as among actresses, opera singers, and ballet girls in civilized communities. Others frequent entertainments that the house of rich men, or public festivals, and estimate their favors at a very high price, while the remainder are avowed harlots, prostituting themselves indiscriminately to any who desire their company. Many of these are devoted to service of some god, whose temple is enriched from the gains of their calling.

The Watul, or Gipsy tribe of Kashmir is remarkable for many lovely women, who are taught to please the taste of the voluptuary. They sing licentious songs in an amorous tone, dance in a lascivious measure, dress in a peculiarly fascinating manner, and seduce by the very expression of their countenances. When they join a company of dancing girls, they are uniformly successful in their vocation, and have been known to amass large sums of money. Now that the valley is in its decadence, their charms find a more profitable market in other places. The bands of dancing girls are usually accompanied by sundry hideous duennas, whose conspicuous ugliness forms a striking contrast to their charge.

The Nach girls are under the surveillance of the government, which licenses their prostitution. They are actual slaves, and cannot sing or dance without permission from their overseer, to whom they must resign a large portion of their earnings.

In addition to these, who may be styled poetical courtesans, there exists a swarm of prostitutes frequenting low houses in the cities or boats on the lake; but of them we have no distinct account. It is certain that they are largely visited by the more immoral of the population, and an accurate idea of their status may be formed from a knowledge of the fact that the traveler Moorcroft, who gave gratuitous medical advice to the poor of Serinaghur, had at one time nearly seven thousand patients on his lists, a very large number of whom were suffering from loathsome diseases induced by the grossest and most persevering profligacy. In short, there can be but little doubt that the manners of the inhabitants of this interesting and beautiful valley are corrupt to the last degree.”

Around this time, stories of young Kashmiri girls being sold in the plains of Punjab were also doing the rounds in writings on Kashmir. These stories were first recorded by a French botanist named Victor Jacquemont who visited Kashmir in around 1831.

On his arrival in the Lahore court of Maharaja Ranjit Singh – the ruler of Punjab and of Kashmir, Jacquemont was treated to “a most splendid fěte” – a performance by “Cashmerian danseuses” who had “their eyes daubed round with black and white”. In a letter he told a friend of his: “my taste is depraved enough to have thought them only the more beautiful for it.” And in a letter to his father he wrote: ” the slow-cadenced and voluptuous dance of Delhi and Cashmere is one of the most agreeable that can be executed.” However, his experience with dancing girls in Kashmir was only of disappointed. In his supreme disappointment, he calls Kashmiri women “hideous witches” and even calls Irish poet Thomas Moore “a perfumer, and a liar to the boot” for essentially writing too beautifully about Kashmir in his famous poem Lalla Rookh. About the dancing girls at Shalimar Bagh her wrote: “They were browner, that is to say blacker, than the choruses and corps de ballet of Lahore, Umbritsir, Loodheeana, and Delhi.” Jacquemont had made up his mind when he wrote: “It is true that all little girls who promise to turn out pretty, are sold at eight years of age, and carried off into the Punjab and India.”

George Forster, who visited Kashmir in 1783, thought that Kashmiri dancers had disappointingly “broad features” and even more disappointingly often “thick legs” too. He was probably the first European to write about Kashmiri nautch girls. In spite of his disappointment he wrote: “the courtesans and female dancers of Punjab and Kashmire, or rather a mixed breed of both these countries, are beautiful women, and are held in great estimation all through Norther parts of India: the merchants established at Jumbo, often become so fondly attached to a dancing girl, that, neglecting their occupation, they have been known to dissipate, at her will, the whole of their property; and I have seen some of them reduced to a subsistence on charity; for these girls, in the manner of their profession, are profuse and rapacious.”

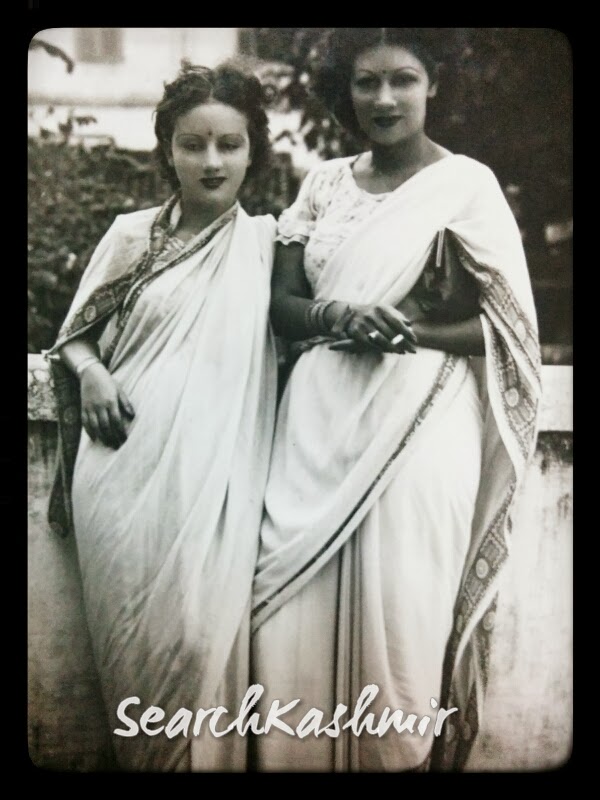

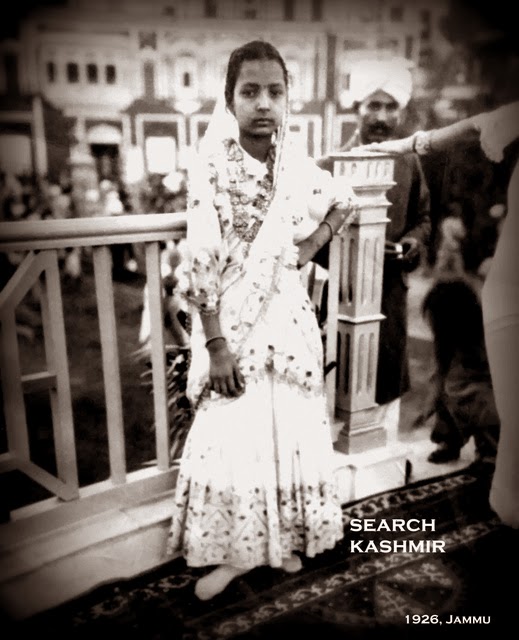

Surprisingly, Jammu can be claimed to have continued this tradition right until the time of legendary singer Malika Pukhraj (1927-2004). She started her illustrious career at the royal court of Maharaja Hari Singh and went on to captivate the entire divided sub-Continent with her beautiful singing.

There is another Jammu angle to the story of Kashmiri Dancing girls.

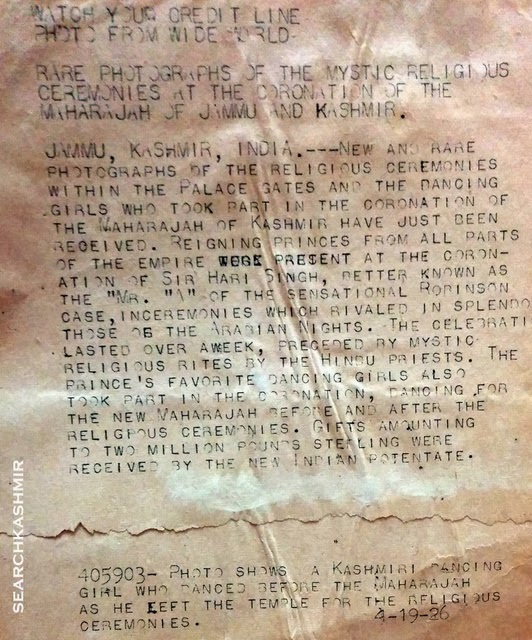

What these early western visitors probably witnessed in Kashmir was a form of Kashmiri singing and dancing known as Hafiz Nagma. The songs are usually set to Sufi lyrics or Sufiana Kalam and the dancer who performs these songs, always female, is known as – Hafiza. These dancers were much celebrated at weddings and festivals.In a Victorian twist, Hafiz Nagma was banned Kashmir in 1920s by the ruling Dogra Maharaja. He felt that this dance form was losing its sufi touch and was becoming too sensual, and hence amoral for the civil society. Now, old traditional songs being the same, in an odd parody, female dancers were replaced by young boys dressed like women to perform on them. It came to be known as bacha nagma and is still popular at Kashmiri weddings. Hafiz Nagma is now almost lost.

-0-

*This particular book first published in 1842 is my personal favorite. The only obvious error I could find in the book is that it got the date of George Foster’s visit to Kashmir wrong. Foster visited Kashmir in 1783-84 and not 1833 as claimed in Chapter titled Beautiful Country that quotes Foster’s visit to Vernag (Verinag). The same was noted in a footnote to C.Knight’s Penny cyclopaedia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1851) while dealing with an article on the life of Francois de Bernier.

** Changus: Village Shangus of Anantnag district.

-0-

Photograph of Shalimar Garden taken by me in June 2008

My post on old photographs of Kashmir included photographs of some of these nautch girls