|

| ‘Jhelum Ghat Scene’ by Brian Brake, 1957 |

-0-

Won’t you come to the Yarbal dear?

I would wash your footlings;

My wounds are unhealed –

Come my Love.

~ Mahmud Gami (1750- 1855)

in bits and pieces

|

| ‘Jhelum Ghat Scene’ by Brian Brake, 1957 |

-0-

Won’t you come to the Yarbal dear?

I would wash your footlings;

My wounds are unhealed –

Come my Love.

~ Mahmud Gami (1750- 1855)

|

| Habba Kadal, 2008 |

“I was in Kashmir. One evening, I sat by the River Jhelum. There was stillness all around. I felt I was sitting besides the Padma. Of course, when I lived on the Padma I was a young man, now I am old. Yet that difference seemed to have been wiped out by some link transcending time. A flock of geese flew over my head across Jhelum…I seemed to hear some ineffable call, and be led by its impulse to some far journey.” (Kshitimohan Sen, Balaka-Kabya-Parikrama,p.55)

Balaka

A Flight of Swans

The curving stream of the Jhelum glimmering in the glow of evening

merged into the dark like a bend sword in a sheath;

at the day’s ebb the night-tide

appeared with the star-flowers floating on the dark waters;

at the foot of the dark mountains were rows of deodar trees;

as if Creation, unable to speak clearly, sought to reveal its message in dream,

only heaps of inarticulate sounds rose groaning in the dark.

Suddenly I heard at that moment in the evening sky

the flash of sound rushing instantly far and farther in the plain of emptiness.

O flying swans

Storm-intoxicated are your wings

the loud laughter of immeasurable joy awakened wonder

which continued to dance in the sky.

The sounds of those wings,

the sounding heavenly nymphs

vanished after breaking the quiet of meditation.

The mountains, engulfed in darkness, shuddered,

shuddered the forest of deodar.

As if the message of those wings

brought for a moment the urge for movement

in the heart of ecstatic stillness.

The mountains desired to be roaming clouds of April,

the rows of trees spreading their wings,

desirous of severing the fetters of earth, were lost in a trice,

while in search of the end of the sky following that trail of sound.

The dream of this evening is shattered.

The waves of agony rise.

There is longing for the far,

O roaming wings.

In the heart of the universe is heard the agonized cry,

‘Not here, not here, but somewhere else!’

O flying swans,

tonight you have opened to me the covers of stillness.

under this quiet I hear

in air, water and land

those sounds of the undaunted and restless wings.

The heaps of grass are flapping their wings in the sky of the earth;

in some dark obscure corner of the earth

millions of sprouting swans of seeds are flapping their wings.

Today I see these mountains, these forests fly freely

from one island to another, from the unknown to the more unknown.

In the beating of the wings of the stars

the darkness starts crying for the light.

I hear the myriad voices of men flying in different groups to

unknown regions

from the shadowy past to the hazy and distant new age.

In my heart I heard the flight of the nest-free bird with innumerable

others

through day and night, through light and darkness

from one unknown shore to some other unknown shore.

The wings of the empty universe resound with this song –

‘Not here, but somewhere, somewhere, somewhere beyond!’

Translated by Bhupendranath Seal (Modern Indian Literature, an Anthology, Volume 3)

“It is becoming easier for me to feel that it is I who bloom in flowers, spread in the grass, flow in the water, scintillate in the stars, live in the lives of men of all ages.

When I sit in the morning outside on the deck of my boat,before the majestic purple of the mountains, crowned with the morning light. I know that I am eternal, that I am anado-rupam, My true form is not that of flesh or blood, but of joy. In the world where we habitually live, the self is so predominant that everything in it is of our own making and we starve because we have to feed ourselves. To know truth is to become true, there is no other way. When we live in the self, it is not possible for us to realize truth.

[…] My coming to Kashmir has helped me to know clearly what I want. It is likely that it will become obscured again when I go back to my usual routine; but these occasional detachments of life from the usual round of customary thoughts and occupations lead to the final freedom – the Santan, Sivam, Advaitam.”

~ extracts from a letter written by Rabindranath Tagore in Srinagar, Kashmir on October 12th, 1915. [A Miscellany by Rabindranath Tagore]

-0-

‘So, the temple! Is it going to fall to the left or to the right?’

We wondered. My grandfather couldn’t remember the way to his house. He didn’t recognize the chowk, the tang adda nor the left turn that led to the house that was once his. When we reached the house, he asked, ‘Is this the place?’

His memory had probably started to disintegrate the previous summer. Memories flowing in his blood were forming a clot in his cranium. In a condition like that, pulling the directions to a neighbourhood temple from memory was perhaps too much to expect. Yet, we engaged in a play. Many a games like these we had played together. The pace at which the bus was moving, everyone had to pick a side or miss having the darshan. Everyone in the bus looked left and then right and then left. I chose right. I knew the temple was to the right. It had to be.

One the the earliest memories of Kashmir I have is of a day, not a particular day, rather sum of many such days, one of those days when my grandfather would take me to the ghat to get monthly ration. On way to the river bank he would tell me about the weir. The weir on Jhelum was built around 1906, an engineering feat performed using British help, to maintain the water level of the river, to keep the river navigational and to keep an old river going. Back then I didn’t know all this. I didn’t realize rivers could die. But the sound of ‘Veer’ excited me. Veer had been part of Kashmiri language for decades now but when I heard the word ‘Veer, I asked him to explain what this Veer thing looked like. What is a Veer?

‘It’s a big wooden structure built across a river…’

One could simply say it’s a small dam like structure but as I heard and misheard and missed my grandfather’s explanation, the picture that my mind chose to draw was no simple dam. My mind took: from the pair of snakes in Medical insignia of Soura hospital, one snake and comity; from the cranky old wooden electric pole in our yard, it took a slippery and wet wooden pole and an uncertainty; from the rows of those giant taps that someone put alongside a railing of an old bridge on Jhelum and then left them all open as if by mistake, a fountainn-tap to pump oxygen (not water) into a thirsty river, it took sound and breath; and from the dying moments of a black and white television screen, it took its last slow murmur of life, a single beautiful dot of blinding whiteness in the center of a finite darkness. A picture emerged, my eyes could now see the Veer: it was an unreadable god, in the middle of a deep river a huge pole reaching for an overcast grey sky, wound around it, a giant dark serpent with inviting diamond twinkle for eyes. Can it call out to people? Can its voice be heard? Why it looked like Skeletor’s ‘Snake Mountain’!

‘That’s way to the Veer,‘ he pointed in a direction, ‘…will take you someday.’ I couldn’t see anything. The vision faded. Or did it appear only later in a nightmare I had on a Sunday. This day must have been a Sunday.

‘Aren’t we going to go?’

‘Maybe later. First we will go get ration. Don’t you want to see the houseboats.’

‘Yes…’

I wanted to see it all. I wanted to run to the shore as soon as the whiff of the river reached me. But before going to the houseboat-shops, grandfather stopped. He stopped in front of a structure that looked like a storeroom. A storeroom with a locked door.

‘Is the shop closed? Will we have to agin come back tomorrow? What do they sell here?’

‘This is our Bhairav Mandar,’ my grandfather answered even as he offered a head-bent namaskar to the iron lock.

‘What’s inside?’

‘God.’

‘Why is it locked? Can we look inside?’

As he proceeded to circumvent the structure, I followed him, holding on to a corner of his kurta and on with my questions.

‘Which one?’

‘What?’

‘Which God?’

‘Bhairav’

Is Bhairav also Shankar?

He then started talking something about chappals.

In the bus, he repeated the old story: ‘They threw chappals into the hawan kund. The government put a lock on the temple and we were barred from praying there. Just like that. The matter went to the court. We agitated. I too fought the police. I think the matter is still in the court.’

He ended that sentence with a snort. For a moment all his memories seemed lucid again. The dispute over the Bhokhatiashwar Bhairov Nath Mandir of Chattabal arose in 1950s and peaked around 1973 when a mob attacked the temple premise which had been a center of cultural and religious activities for Pandits of Chattabal. Food Control department of the State government laid claim over the temple’s ghat. Pandit fought back the claim with a surprising resolve. They were out on streets facing police lathicharge. The matter reached the court which locked down the temple structure till a verdict was reached. But the verdict never arrived. In 1990, the families of people who took part in temple agitation were doubly afraid for their lives. There were old scores to be settled. As their temple was already locked, temporarily, they locked their houses too. The locks remained until 1992 when, in the aftermath of Babri Masjid Demolition, Bhairav temple, like many a Pandit houses, lost its lock, lost its door, windows, roof, the walls and the stones and anything valuable or un-valuable or invaluable inside. Does it make sense? Any of it. Talking about a temple in Chattabal and a temple in Ayodhya. Love may not tie humanity, but the violence already does. Does violence offer greater intimacy? Is Chappal a God too?

My grandfather didn’t take me to the weir that day. I never saw it. But I did try to find it, on my own many time. I was just starting to discover the place where I was born. I had started to walk out of the house alone, tracing the by-lanes, just to see where they led, to a bridge or a river, or a dead-end or a grocery, or a butcher’s shop. Out for running home errands, buying eggs, butter, milk or zamdod, followed by crows and eagles, cats and dogs, horses and tongas, I would sometimes take a new route, take a wrong turn, just to see how far I could go before that ‘lost’ feeling churns in stomach. On these walks, one of the boundaries of my daring adventures, Lachman Rekha of my kingdom, my point of ‘better-return-back-home’, was a bridge from which I could see the houseboats on the ghat. Somewhere near this bridge, to the left, was a shop that sold mint candies that looked like Digene pills, only, white and not pink. White like those white pebbles used to emboss Gurmukhi Omkar above the door of that Sardarji in Chanpore near Massi’s house. Didn’t I always want to pluck those white dots out from that wall, just to confirm they were in fact not edible? Is Chappal a God too? Did I really ask Daddy that question? How after long walks with Nani on the dry river bed of Tawi in Jammu, on a river bed baked red in summer sun, I used to bring back to her those beautiful stones. She would ask us kids to look for a Kajwot, a perfect grinding stone, and we would run back to her carrying a stone with white stripes around it, a mark like a Brahmin’s yoni, a janau. ‘Ye ti Shivji‘, she would exclaim and send a little prayer. We would pocket the god. Few minutes later we would again run back to her to confirm if we had again found another god. The river bank only had too many gods and too few Kajwots to offer. She would again say a prayer. Our pockets were too small and the world had too many stones. We would throw the stones in the river. While we looked for a perfect Kajwot, she would often talk about Doodhganga. We used to have these walks in Kashmir too, in Chanpore, on the dry bed of a river called ‘Milk Ganga’. They say in the old days a single stream of milky whiteness used to flow in the center of that muddy river. Hence the name.

‘Where could that shop selling white mint candies be? That was to the left of the bridge.’ I wondered and turned my head left to look for the shop.

‘There. To the right. There somewhere should be the temple. Yes, there it is. The ruins. All burnt.’

‘Where? Where?’

I had missed it. In the mad dash, I couldn’t see a thing. Facing right, staring as a fast passing train of trees, shacks, a muddy river, a dry river bed, a rolling polythene bag, empty crushed plastic bottles, metal of electric poles and wires, I could see. I couldn’t see the temple. I kept shooting the camera blindly, hoping to capture something, anything. The moment passed just as it came. Did I miss it? I believed I did. I wanted to see the place where my father used to accompany his father to buy cheap American IR-8 rice in 1906s. I wanted to see the temple. The boats. I wanted to see the veer.

‘I think it is settled.’

Grandfather exclaimed solemnly. After a brief pause he added, ‘This is how things are settled…conflicts resolved.’

A sad laughter escaped deep from his throat and turning away from the car window, he went back to reading a local Urdu newspaper from Kashmir.

-0-

|

| From the looks of that towel left for drying on the window sill, somebody actually lives in that house. Update: The place is known as Aabi Guzar. Apparently at this place people used to pay taxes for using the water ways. 2010. |

Update:

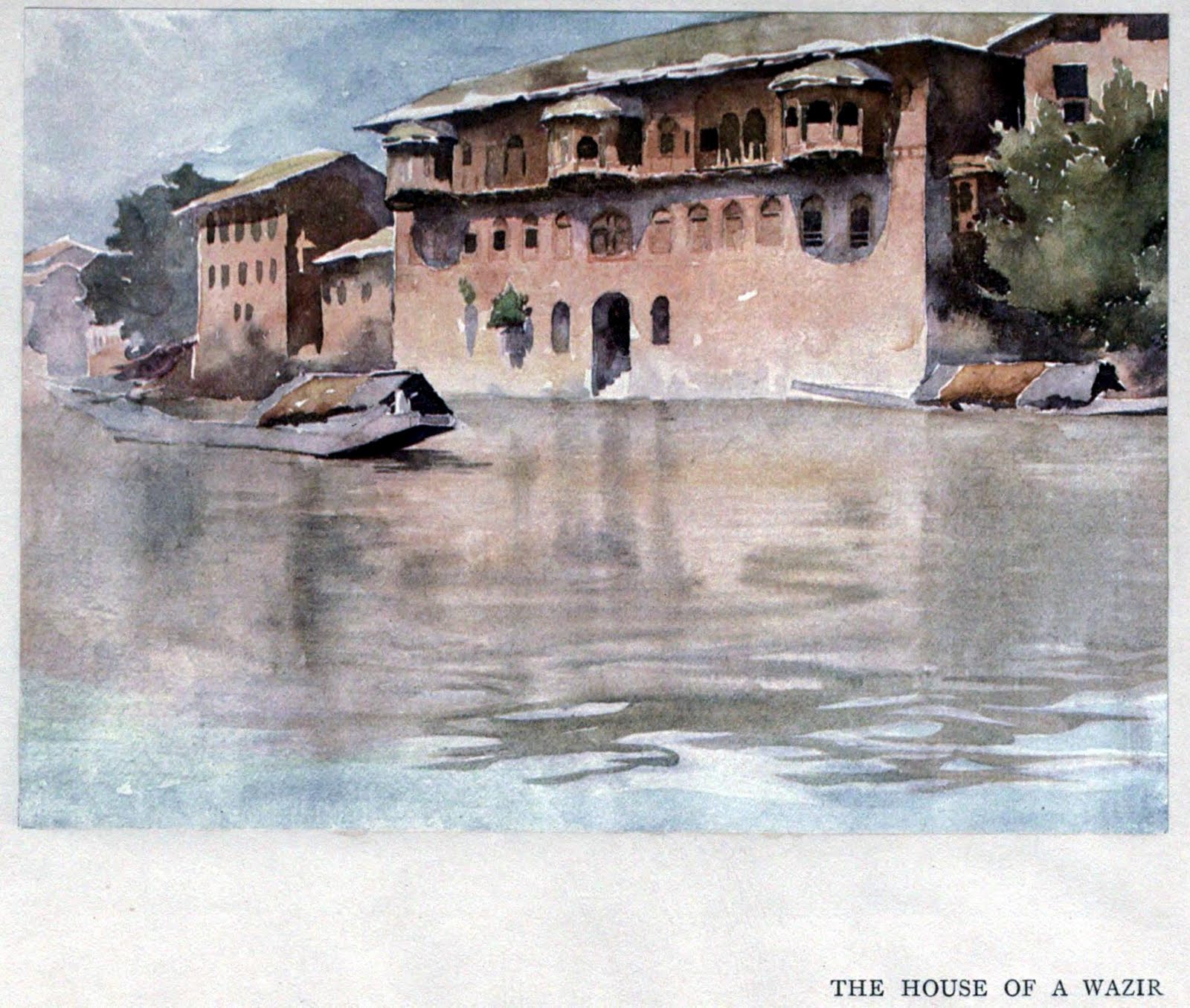

Notice the design.

Drawn by H.R. Pirie for P. Pirie’s ‘Kashmir; the land of streams and solitudes’ (1908).

|

| Morning at Zero Bridge |

|

| Morning at Dal Gate |

|

| Morning at Gulmarg |