Near But Kadal in Zadibal, Srinagar, is a 15th century monument known as ‘Madin Sahib’ named after the tomb and mosque of Sayyid Muhammad Madani who came to India with Timur in 1398 and moved to Kashmir during the reign of Sultan Sikandar Butshikan (1389–1413 CE). The monument comprises of a Mosque and a Tomb, with the mosque dating back to around 1444 which first came up during the reign of Zain-ul-Abidin, incorporating elements from an older Hindu monument.

In 1905, archaeological surveyor W. H. Nicholls (1865-1949), during his pioneering study of Muslim architecture in Kashmir, was the first to notice the uniqueness of the art of this building among all the Muslim monuments in India. The mosque had glazed tiles of a kind unlike any other building in India and some tiles was painted a mystical beast not seen anywhere on any other mosque in India. The beast could be seen in the tile work on left spandrel of arch at entrance.

Nicholls wrote in a report:

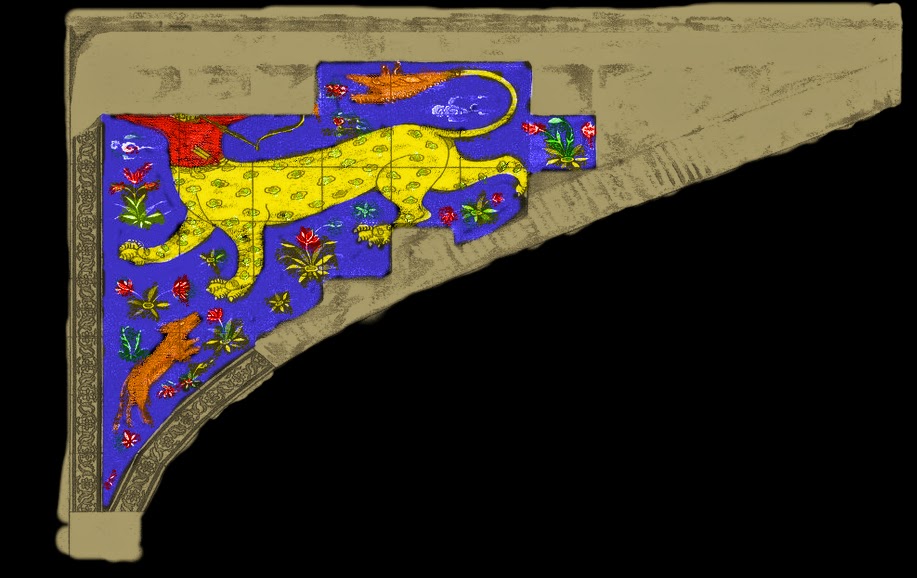

“a beast with the body of a leopard, changing at the beck into the truck of a human being, shooting apparently with a bow and arrow at its own tail, while a fox is quietly looking on among flowers and cloud-forms. These peculiar cloud-forms are common in Chinese and Persian art, and were frequently used by Mughals – by Akbar in the Turkish Sultana’s house at Fathepur-Sikri, Jahangir at Sikandarah, and Shah Jahan in the Diwan-i-Khass at Delhi, to mention only a few instances. The principal beast in the picture is about four feet long, and is striking quite an heraldic attitude. The chest, shoulders, and head of the human being are unfortunately missing. The tail ends in a kind of dragon’s head. As for the colour, the background is blue, the trunk of the man is read, the leopard’s body is yellow with light green spots, the dragon’s head and the fox are reddish brown, and the flowers are of various colours. It is most probable that if this beast can be run to earth, and similar pictures found in the art of other countries, some light will be thrown upon the influences bearing upon the architecture of Kashmir during a period about which little is at present known.”

Nicholls supposed the figure like the main building too came up in 1444, which would make it pre-Mugal. However, John Hubert Marshall (1876-1958), superintendent of the Archaeological Survey of India, in his introduction to Nicholl’s report mentions that a Persian text at the site indicted that the present entrance was added during Shah Jahan’s time (1626 to 1658), that would make it from 17th century and not 15th century. [More recently inscriptions have been found from the time of Dara Shikoh too]

|

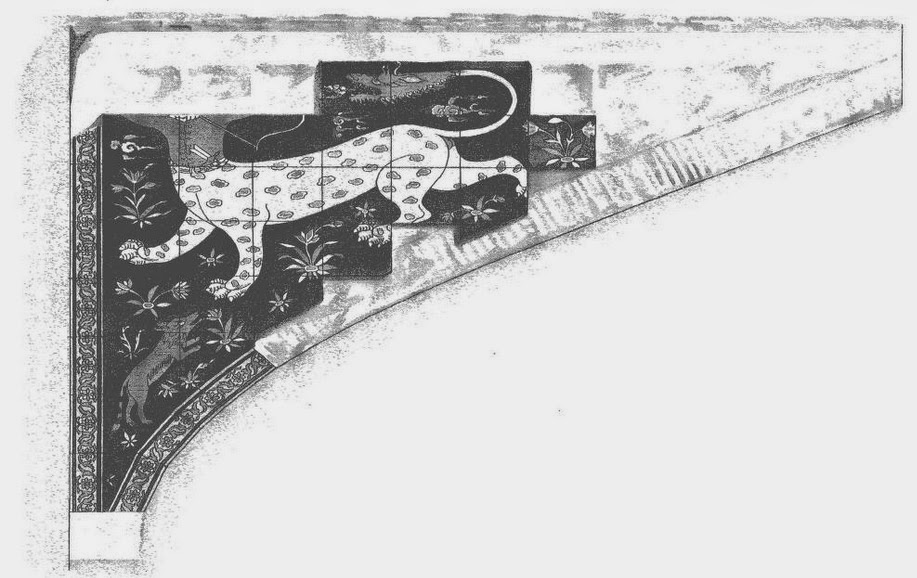

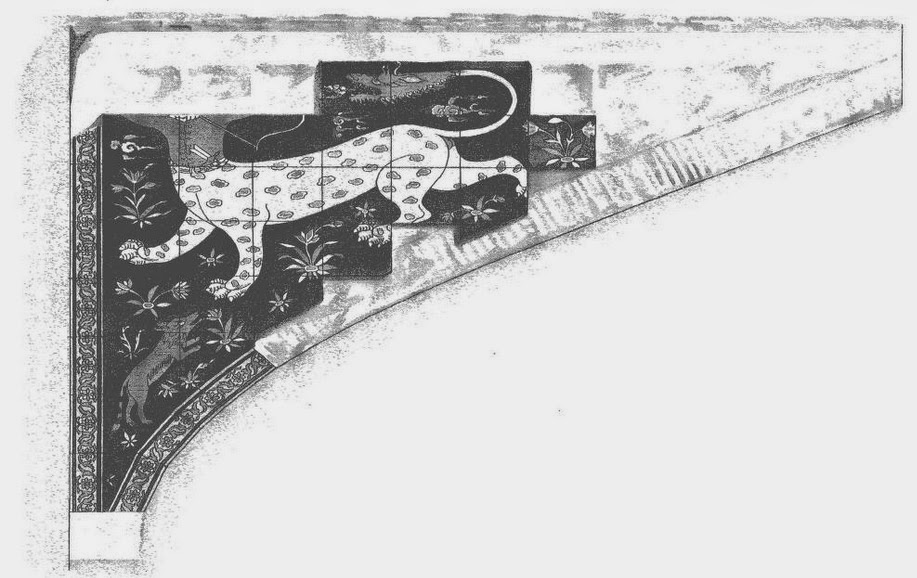

Beast as drawn by W. H. Nicholls in his

Muhammadan architecture in Kashmir by Mr. W. H. Nicholls

for ‘Archaeological Survey of India Report 1906-7’ [uploaded here]

Digitally distorted copy as made available by Digital Library of India |

Although the figure was unique and the description by Nicholls was repeated verbatim often when talking about architecture of Kashmir. The mystery beast wasn’t explained till recent times in obscure journals. And even then there is much confusion.

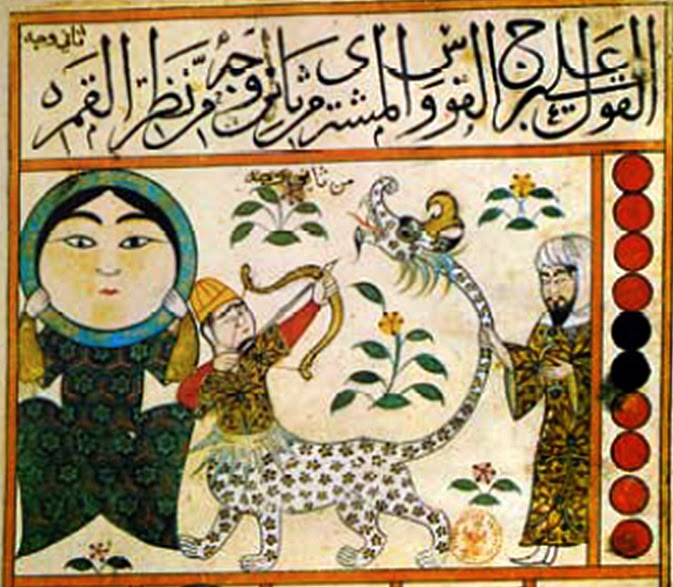

Using Google Image search, it took me just five minutes to figure out that the image stands for the Islamic astrological figure representation of eclipse happening in Sagittarius or centaur (ai-qaws), the bow man represents the planet Jupiter, while the dragon is al-jawzahar, the devouring pseudo planet. The concept of 8th planet coming after the 7 planets (the sun, the moon, saturn, jupiter, mars, venus and Mercury), is supposed to reached Sasanian Empire from Indian Astrological concept of Rahu (head) – Ketu (Tail), the two (but 1) pseudo planet(s), a giant dragon that occasionally devours planets, a concept that made its way into all major schools of eastern astrology.

In case of Sagittarius, the eclipse is a weak, hence the Bowman is shown defiantly shooting into the mouth of the dragon (Rahu).

Such figures could be (and can still can be found) from the time of Abbasid Dynasty in region as wide as Iraq to Iran. Abbasid calip Abu Ja’far al-Mansur (r. 754-75) is said to have built his capital at Baghdad under the astrological sign of Sagittarius. In Iran, it is very common in Isfahan, a place whose symbol is Sagittarius, having something to do with the year the city came up in 16th century around 1591 with defeat of Uzbeks. Sagittarius represented meant realm of Persia around this time. The building with Sagittarius in Iran came up mostly came up in 16th century. However al-jawzahar showing up on a building in Indian sub-continent is unique. It is interesting that the monument falls in the Shia locality and is claimed by them. There was colony of Persian traders at the place till 1830, when religious riots forced them to move back to Iran.

|

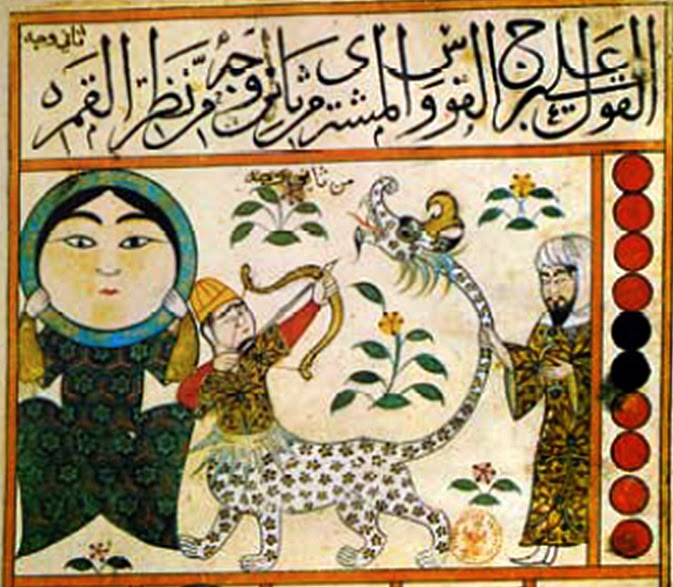

Sagittarius in Persian astrological treatise from 9th century,

‘Kitâb al-Mawalid’ by Abu Ma’shar al-Balkhi

Also known as ‘The Book of Nativities’ or ‘The Book of Revolution of the Birth Years’.

One of the most influential works from Islamic astrology |

|

Sagittarius on the entrance to the bazaar of Esfahan

source |

In 1926, some of the tiles from the monument were moved to Victoria and Albert Museum. The tiles were described to be coloured in “iron-red, manganese-purple, tin-white, copper-green, cobalt and copper blues, on an opaque antimony-yellow ground. Height 8 inches, width 32 inches.”

The Sagittarius figure however was to be found on the entrance just until 1983. The tiles were then moved to Central Asian Museum (University of Kashmir, Srinagar).

In this photograph from 1983 for the renovation happening at the place, the tiles on entrance are missing. Some additional tiles (some of the missing pieces of the Bowman) were found in rubble and now stay at SPS Museum, Srinagar.

|

Prataap Patrose, Aga Khan Visual Archive, MIT

source |

|

| The actual sketch of the beast by W. H. Nicholls in 1905 |

|

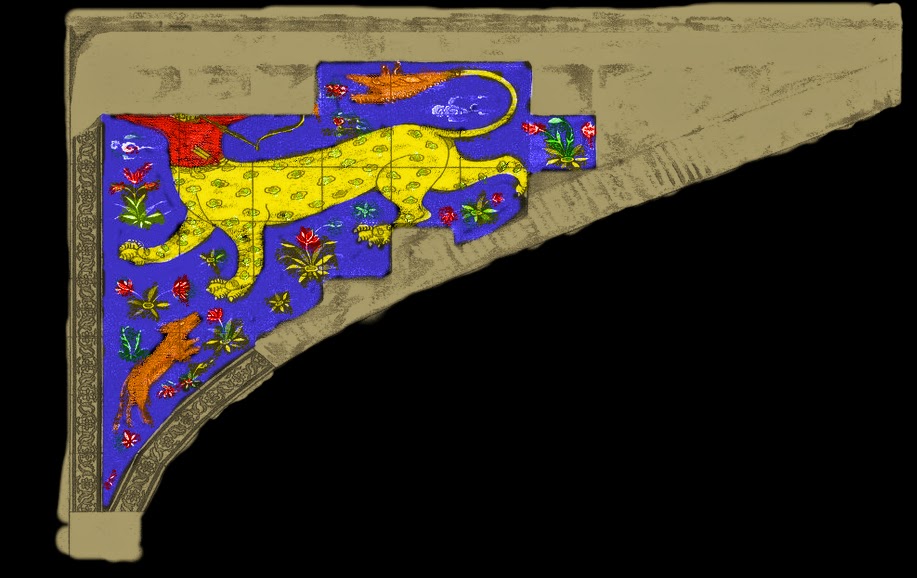

A color version I tried to create using GIMP. Color palette based on description by Nicholls and of the tiles at Victoria and Albert Museum. |

|

The missing pieces Sagittarius tile not given in the sketch of Nicholls

at SPS Museum

November 2014

The cations for the display of course don’t tell you the story of the tile

-0- |

In 1994, archeologist Ajaz Banday in Srinagar did identify the image as Sagittarius and yet the image continues to baffle people.

In 2011, Aniket Sule tried to explain the figure as ‘Indian record for Kepler’s supernova: Evidence from Kashmir Valley’ [

pdf link]. The writer tried to explain the dragon spitting fire as representation of

Kepler supernova witnessed in 1604.

An argument to the contrary was provide by Robert H. van Gent in his paper ‘No evidence for an early seventeenth-century Indian sighting of Keplers supernova’ (2012) [

archive.org link], placing the image well back in Islamic astrological iconography. (As explained a simple google image search would have stopped anyone from superimposing supernova on that figure)

-0-

Interestingly, Sagittarius, it seems, was always watched closely by Muslim astronomers and astrologers.

In 1575,

Taqi ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ma’ruf, court astronomer of Sultan mural III (reigned 1574-1595), established an observatory in Istanbul. This was the last great observatory built in Islamic empire. When t

he Great comet of 1577 appeared in Sagittarius, Taqi al-Din predicted that Turkish army would win against Persian. The Turkish army did win but the losses for Turks was also great. And then in the same year some important men of the court died, this was follow by plague. Taqi’s rival astrologers and clerics convinced the Sultan that observatory was the cause. The observatory was destroyed in around 1580. This destruction of the last Islamic observatory almost coincides with the construction of first modern observatories in Europe by

Tycho Brahe.

Johannes Kepler, all of age six, was among the people who witnessed the great comet of 1577 and later went on to assist Brahe, and much later helped change the way people look at sky forever.

-0-

–

Further read and references:

The Dragon in Medieval East Christian and Islamic Art (2011) by Sara Kuehn

Slaves of the Shah: New Elites of Safavid Iran (2004) edited by Sussan Babai

A History of Physical Theories of Comets, From Aristotle to Whipple (2008) by Tofigh Heidarzadeh

Jews, Christians, and the Abode of Islam: Modern Scholarship, Medieval Realities (2012) By Jacob Lassner