‘Not a lot of Pandits used to go there, certainly not the older generation. They would go to Makhdoom Sahib on Parbat but seldom to Hazrat Bal. But younger generation had started exploring.’

The image of the famous Srinagar mosque that now comes to mind is of a hard marble dome and a minaret on the banks of Dal. But it wasn’t always like that.

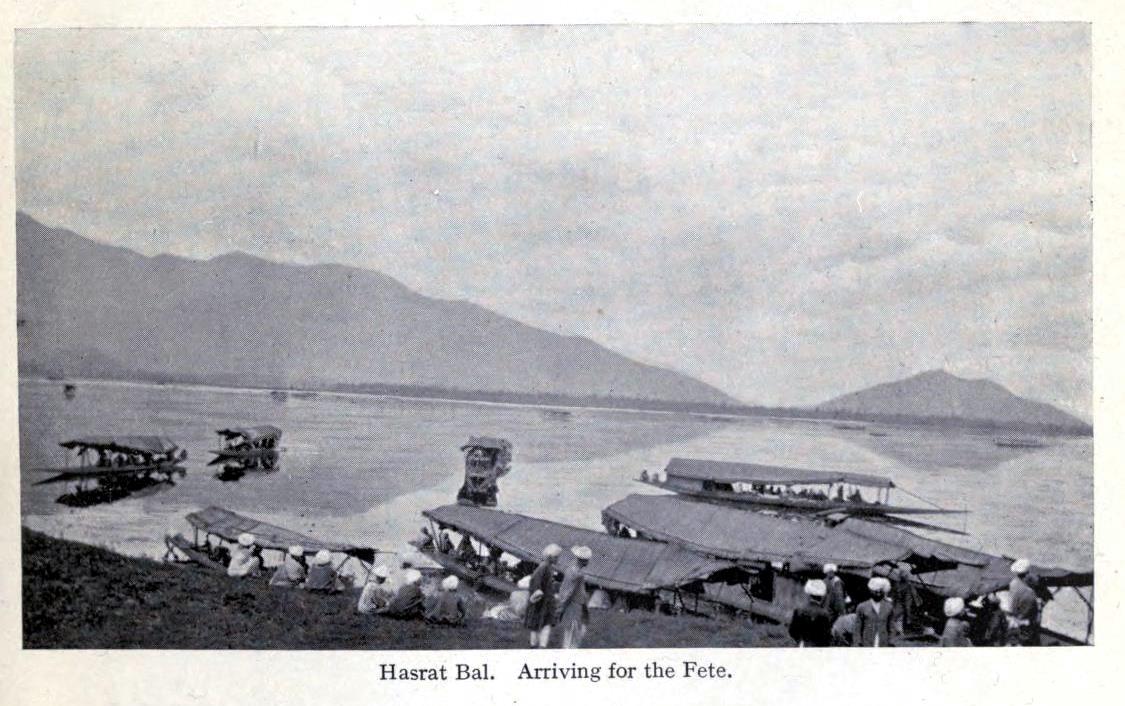

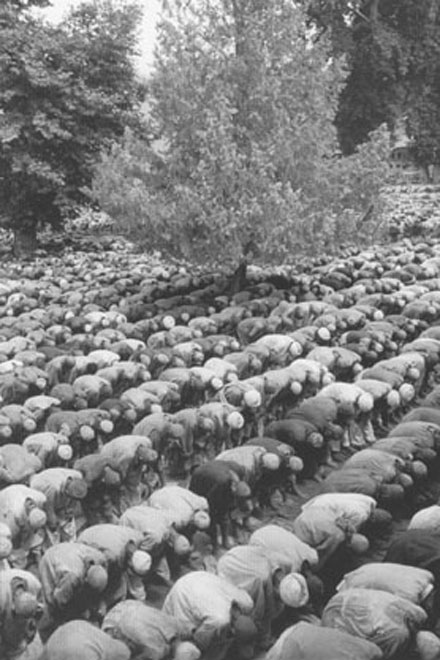

Here are photographs of the old Hazrat Bal in around 1917 that I came across in a wonderful book titled ‘Cashmere: three weeks in a houseboat’ (1920) by Ambrose Petrocokino.

|

| Hasrat Bal. Arriving for the Fete. |

|

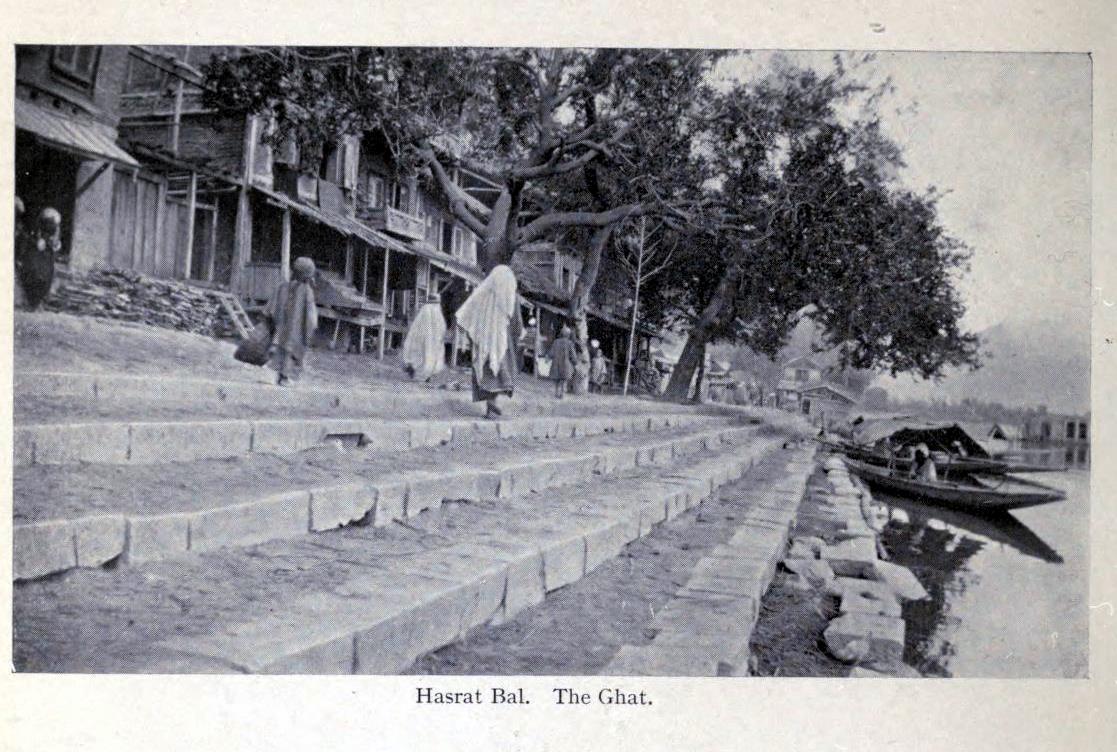

| Hasrat Bal. The Ghat. |

|

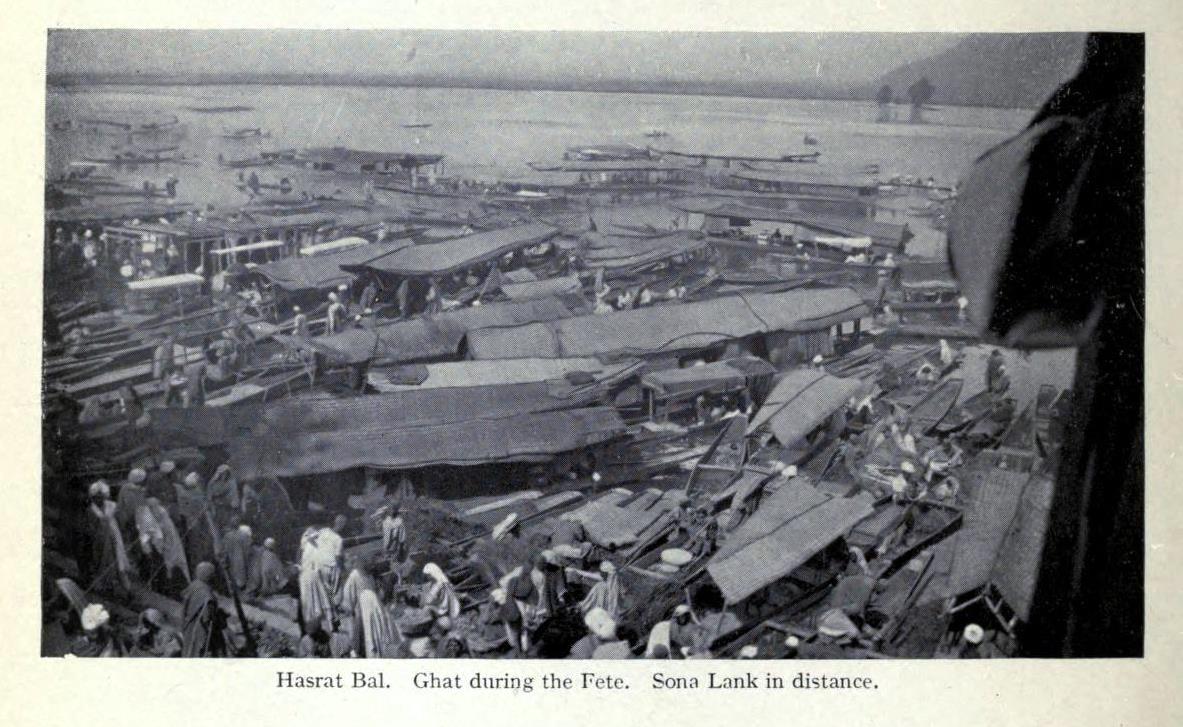

| Hasrat Bal Ghat during the Fete. Sona Lank in distance. |

|

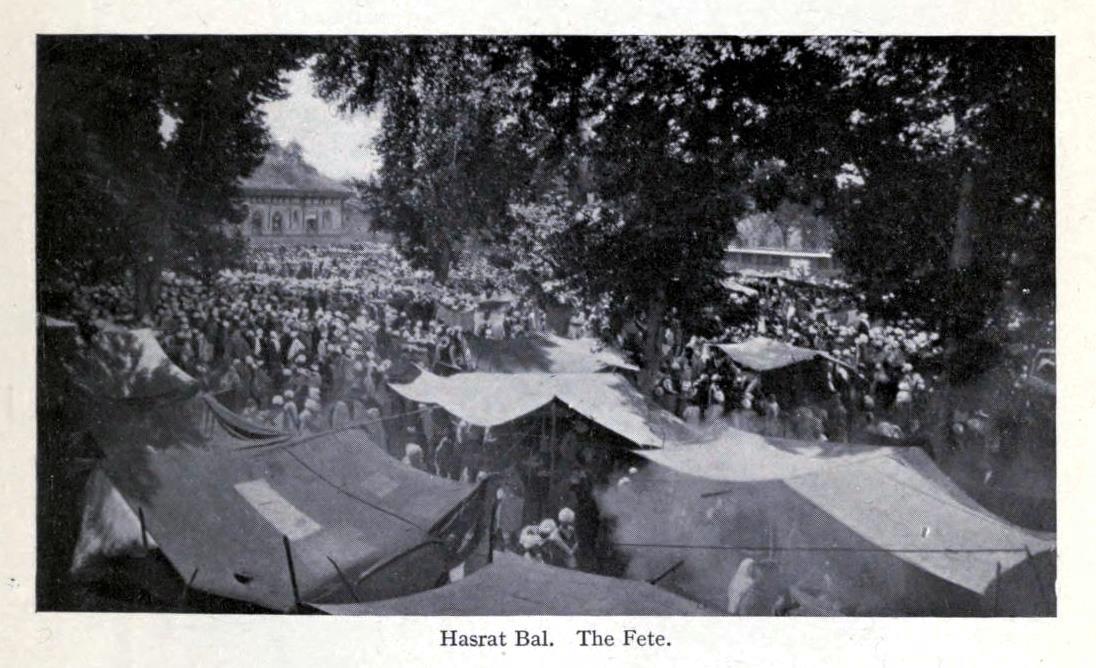

| Hasrat Bal. The Fete. |

|

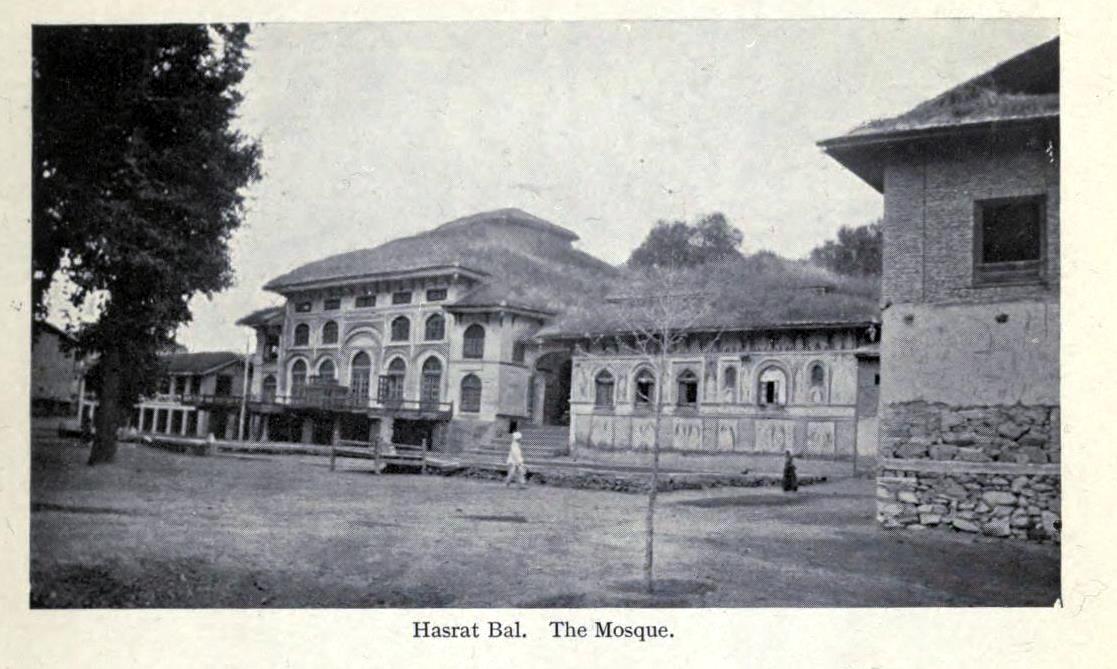

| Hasrat Bal. The Mosque. |

The story of the spot goes back to Mughal times when Sadiq Khan, the governor sent in by Shah Jahan, built a garden and palace at this picture perfect spot on the side of Dal. He called it Ishrat Mahal or the Pleasure House. It was 1693 and in time the place around it came to be known as Sadiqabad or Bagh-i-Sadiq. When Shah Jahan visited the place in around 1634, he converted the pleasure palace into a mosque. Around the same time, in around 1635, a holy relic was brought to India by one Sayeed Abdullah, a keeper at Kaaba, who settled somewhere at Bijapur in the state which in now known as Karnataka.. Syed Hamid, son of Sayeed Abdullah, having fallen on hard times after Aurangzeb’s conquest of Bijapur, sold it to a Kashmiri trader named Khwaja Nur-ud-Din Eshai. One knowing about the sale of such an artifact, Aurangzeb imprisoned the Kashmiri trader at Lahore on charges of perpetrating hoax, but later had the said relic sent to the shrine of Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti at Ajmer. Aurangzeb later had a change of heart (some say it was ‘divine intervention’) and allowed for the relic to be sent to Kashmir. But by this time Nur-ud-Din Eshai was already dead in prison, so the relic was brought to Kashmir in around 1699 by his daughter Inayat Begum whose progenies came to known as Nishaandehs – keeper of the sign. Initially, the relic was kept at Naqshband Sahib Shrine at Srinagar. But soon, keeping in mind the growing number of people thronging to take a look at the relic, a new place for keeping the relic was proposed – the shrine at Bagh-i-Sadiq. And so moi-e-muqaddas was placed at the shrine that came to be referred as Madina-i-Sani and Dargah-i-Sharif. The mosque was set to distinct Kashmiri architecture – wood, slanting roof and iris on the roof. The present look of the shrine came in around as late at 1968 when Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah as head of Muslim Auqaf Trust had the old structure dismantled and started work in a new structure. This new structure was completed in around 1979.

-0-

Aside: To get a better understanding of the politics and economics of Shrine culture in Kashmir, do check out Chitralekha Zutshi’s ‘Languages of Belonging: Islam, Regional Identity, and the Making of Kashmir.

-0-

Update:

“All round the sides of the Dal Lake there are broken walls and terraces, the remains of early Mughal gardens. Hazrat Bal, the village close to the Nisim Bagh, stands on the site of one of these. The large mosque, where the hair of the Prophet is preserved, and specially venerated once a year at a great mela, is built round the principal garden-house. The narrow stone water- course runs beneath it, and through the village square, in the midst of which a beautifully carved stone chabutra figures conspicuously and still forms a convenient praying platform. The old entrance can be seen in the long line of stone steps leading down to the water, but the most interesting feature at Hazrat Bal is the carved stone fountains. ”

~ C.M. Villiers Stuart’s ‘Gardens of the Great Mughals’ (1913)

Sabziwol, Vegetable Seller at Hazratbal

Sabziwol, Vegetable Seller at Hazratbal