Biloreen saaq, seemeen tan, samman seena, sareen nasreen,

Jabbeen chuy aayeena aayeen ajab taaza jilaa, Jaa’noo

Crystal Legs

Body Mercury

Jasmine Bosom

Daffodil Butt

Forehead,

a wondrous

polished

mirror,

my love

in bits and pieces

Biloreen saaq, seemeen tan, samman seena, sareen nasreen,

Jabbeen chuy aayeena aayeen ajab taaza jilaa, Jaa’noo

|

| Nayikas in Rasamanjari. Basohli Painting (~18th Century). |

At the side of the bed

the knot came undone by itself,

and barely held by the sash

the robe slipped to my waist.

My friend, it’s all I know: I was in his arms

and I can’t remember who was who

or what we did or how

-0-

The Rafi song from Shabab (1954) [movie link], the initial line is from Zauq and rest of the lyrics are by Shakeel Badayuni.

Shabab (1954) was inspired by love story of 11th century Kashmiri poet Bilhana. The original story is available as: Bilhaniyam, play written by Narayana Shastri, then there is BilhaniyaKavya and the Bilhaniya-Charitra. And as Bilhaniyamu, a late-eighteenth-century Telugu reworking of a Sanskrit poem, deemed immoral in Victorian era. The episode is said to taken place in court of King Anhil Pattana of Gujarat, and may or may not have been biographical.

In the story, Bilhana is introduced as a blind man to a Princess he is supposed to teach. The princess is introduced to him as a leper. All this so that the handsome man does not seduce the Princess. But the ploy is exposed when Bilhana accidentally, in a moment of joy, describes in lucid details beauty of book. The veil of deception is lifted. The two naturally do end up falling in love. The King, of course, is not happy. So, ‘Off with the head’, he goes. While in prison, Bilhana composes 50 erotic verses that come to be known as Chaurapanchasika (the Fifty Stanzas of Chauras)[a vintage English edition]. There are multiple versions to the story. In the Southern version, the King is impressed by the verses, and the two get together. In the Kashmiri version, the poet awaits the judgement.

In the film version, to keep with the cinematic trends of the time, Bilhana meets a Devdas-ish end. And so does the heroine.

-0-

Interestingly, there is South Indian film from 1948 called Bilhana inspired by the same story.

Did the Pandit boys, who were probably not even allowed to have Tomato, wonder if paper is Satvik or Tamasic?

-0-

|

| An Ad from The Indian Express dated December 9, 1942 |

|

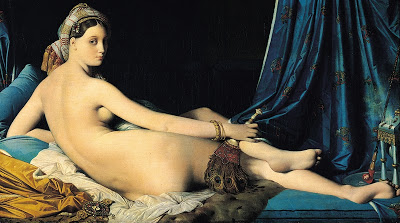

| Grande Odalisque (1814) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. The painter added a couple of extra vertebrae, an anatomical inaccuracy, to make the painting more alluring, more eastern, he made the back of the woman more serpentine. |

|

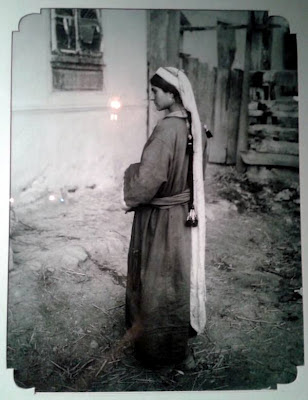

| ‘Serpentine Head Gear’ Kashmiri Pandit Woman. 1939. [By Ram Chand Mehta] A recently heard a Pandit priest claim that all Kashmiri women come from ‘Nagas’ or the Snake race. |

|

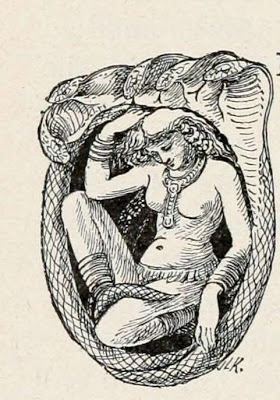

| The snake woman or Lamia by J. Lockwood Kipling, father of Rudyard Kipling. It accompanies the story of ‘The snake-woman and the king Ali Mardan’ in ‘Tales of the Punjab : told by the people’ (1917) by Flora Annie Webster Steel (1847-1929). Another version of the story can be found in ‘Folk-Tales of Kashmir’ by Rev. J. Hinton Knowles (Second Edition, 1893. Narrated by Makund Bayu of Srinagar), in which the snake woman claims to be Chinese and Ali Mardan Khan, actually the Mughal governor of Kashmir, builds Shalimar Garden for her. In Kashmiri the name for the snake is given as Shahmar. |

-0-

Kadru, is the mother of Nagas, and wife of Kashyap, the mythical creator of Kashmir. In, Adi Parva, we learn that Kadru cursed her offsprings for not doing her bidding. The curse with played out by King (Arjun’s great-grandson) Janamejaya’s famous Snake Sacrifice. The serpent race was saved by intervention by Astika, born of wedlock between Rishi Jaratkaru of Yayaver and Manasa, sister of Vasuki Naga.

[Near Jammu, Mansar Lake is the spot associated with Mansa Devi. One of the early description of the Lake can be found in Vigne’s travelogue from 1842]

-0-

-0-

Original painting by Mortimer M. Menpes

Found the lines and translation in Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: sasay to zorgot edited by Mohan Lal, from a section by Shafi Shauq on the poet.

A rendition of the lyrics, @Youtube