Following is an extract from “Kashmir: The Untold story of Men and Matters” (1987) by B. L. Kak (1941-2007). The section “Fever and Fear” offers the readers a glimpse of the regressive tide that was building up in Kashmir at the end of 80s. How the violence of 1990 was just the natural outcome of the movement or tahreek that was underway in the crevices of Kashmiri society and how this society was inverted and conformed till regressive voices became mainstream voice of the populace. Like all violent right wing projects, the “revolution” starts as a cultural project in which books are the first targets and the last step in a call to arms.

“Knowledge is a treasure; zeal without knowledge is like a fire without light .” A reality, as it is. And you cannot refute it. Ironically, however, most of the Kashmiri Muslims have proved themselves opponents of all books of knowledge. Instances, in this connection, are numerous. A thing of the past, though, became quite an event in Kashmir in April 1982. The police went against a local writer. The step against him was, curiously, ordered about four years after he printed his book in Urdu language in Srinagar and circulated in parts of the State in May 1980. And the unostentatious writer, Tej Bahadur Bhan, was baffled by the action against him. Indeed, immediately after his arrest, he pleaded for a quick answer from a police official to his question: “Have you gone through my book”? It was not for the police official to have an academic discussion with Bhan as the latter had been rounded up on the charge that his bool contained some objectionable material.

On the other hand, however, Bhan’s close associates were intrigued when police lifted him and kept him in detention, though for a brief period. It was not unknown that Bhan’s arrest had followed the protest demonstration by activists of the militant Jamait-i-Tulba in Baramulla, 32 miles from Srinagar, against the book – “Pehchaan”. Scores of Kashmiris, especially writers and intellectuals, found it difficult to appreciate the police action against Tej Bahadur Bhan. It was apparently in this context that 17 known writers and artists, including Ali Mohammad Lone, Autar Kishen Rahbar and Bansi Parimoo, demanded Bhan’s release as, according to them, his detention had violated the freedom of expression. Happily for Bhan, some opposition and Congress (I) members in the Indian Lok Sabha, in Delhi, also condemned the government, headed by Farooq Abdullah, for the writer’s arrest after he had supported Darwin’s theory of evolution in his book.

While most people began to think that this Darwin hatred had come rather late, Muslim fundamentalists in Jammu and Kashmir were dead earnest about keeping the “corrupting” influences away. These fundamentalists found Bhan’s book highly objectionable and demanded it be banned and the writer prosecuted. There was already a long list of banned books in Kashmir and most people outside the State might have been surprised to find Bhagwat Gita in the ban lost of Kashmir varsity. A case charging Bhan with attempt at hurting the sentiments of a particular community was registered. And Ali Mohammed Watali, then DIG of police, said that the police had launched a careful study of the issue. This was one positive fallout of the controversy since the study of the book could at least initiate policeman to literature and other intellectual pursuits.

That was the time when Kashmir’s education department found itself in a quandary. A serious problem had cropped up, making it difficult for the authorities to support the quoted saying: “Knowledge is a treasure; zeal without knowledge is like a fire without light.” In other words, valuable protestations by a section of the Muslim fundamentalists against the introduction of NCERT syllabus in educational institutions in the State created practical dilemma for the policy-making body in education department. Jamat-i-Islami and Tableegul Islam were credited with a success after the Farooq government did not hesitate to oblige them by proscribing a book on history meant for 6th standard in schools covered under the NCERT syllabus. The banning of the book, which allegedly contained derogatory reference to Islam, had further encouraged a section of the Muslim fundamentalists to demand withdrawal of NCERT syllabus itself.

During G.M. Sadiq’s tenure as Chief Minister the Muslim militants had whipped up popular sentiments against a famous printed document titled “Bool of Knowledge” which allegedly contained some anti-Islamic material. Demonstrations were organised against the existence in Kashmir of the book. Gripped by religious frenzy, demonstrators had attacked foreign tourists in skimpy clothes and a stinging treatment was given to a few European women – nettle was rubbed on their exposed legs. At the boulevard of the Dal Lake in Srinagar, a foreign tourist was compelled to shout “ban Book of Knowledge”. But the ingenious foreigner with unconcealed sarcasm [shouted] “ban all books of knowledge”. The Sadiq government soon proscribed the book and also unconditionally released those arrested for violence during the agitation.

After Shiekh Abdullah’s return to power in 1975, Muslim fundamentalists succeeded in removing several books from educational institutions and reference libraries. These books included studies on Darwin’s theory of evolution, A Short History of the World by H.G. Wells and Monuments of Civilisation. The last mentioned book contained a pencil sketch of the Prophet and this sparked off angry demonstrations, starting from the Kashmir University, and resulting in a series of violent incidents. Jamat-i-Islami was then accused of having incited the agitation, but the charge was stoutly denied by party president, Saduddin, who asserted that it was his party’s intervention that had saved the situation. However, a section of Kashmir University students complained to the then Governor, B.K. Nehru, that the party and its youth wing, Jamait-i-Tulba, were injection communalism into campus life. It was alleged that followers of these organisation had tried to build a mosque on the campus and also sought closure of the unique Central Asian Museum.

The campaign against the museum was started after the museum claimed to have identified a figure on the coloured tiles of the building to be that of said-philosopher, Syed Mohammed Madani Ali Kashmiri. Popularly known as Madin Sahen, the saint came to Kashmir in the 15th century from central Asia. he and his son were buried near a mosque at Zadibal on the outskirts of Srinagar. The museum survived the closure campaign thanks to stiff opposition from many influential Kashmiri Muslims, including Shiekh Abdullah. interestingly, in view of the attitude of the fundamentalists, booksellers in the State began to ensure that the books they put on sale were non-controversial. A leading bookseller in Srinagar had to engage an experienced Muslim teacher to go through several books on Islam before he put them on sale. Similarly, many librarians had voluntarily removed such books and periodicals that could provoke the irascibility of fundamentalists.

Even after the formation of the Congress (I) backed government headed by G.M. Shah a serious development had taken place with the high-pitched cry for Islamic order in the Muslim-majority Kashmir. The cry and unhindered actions by a section of the Muslims to communalise the situation perturbed most of the Hindus, particularly those residing in villages. And although the authorities in Srinagar and Delhi reaffirmed their resolves to stamp out the evil of communal politics, the growth in the activity of Islamic fundamentalists in towns and villages of Kashmir had become a reality with a phenomenal increase in the number of protagonists of Islamic order in a decade. The decade that was: June 1975 to June 1985. With the removal of Congressmen from power in February 1975, hundreds of Muslim fanatics got an opportunity to intensify behind-the-scene efforts on the need for the preservation of Muslim character of Kashmir.

Even Sheikh Abdullah, after his installation as the Chief Minister in 1975, was found encouraging actions designed, as they were, to unite Muslims and to increase the number of Islamic institutions, including mosques, not only in the two capital cities of Srinagar and Jammu but also elsewhere on the State. The Sheikh called himself a secularist. And yet he always advocated the need for the preservation of Muslim character of Kashmir. True, as the ruler of Kashmir for over seven years, he did not allow his opponents belonging to the Muslim-dominated groups to grow. But these opponents belonging to the right-wing Jamait-i-Islami, Jamait-i-Tulba, People’s League, Mahzi Azadi and People’s Conference were not prevented from open and secret attempts to strengthen and widen Islamic centres.

New Delhi had been apprised of the Shiekh’s unwillingness to know out those Muslims who had engaged themselves in activities seeking establishment of more and more Islamic institutions, particularly mosques, in Kashmir. But the ruling party at Delhi could not assert itself simply because of the Sheikh’s capacity to whip up passions of his con-religionists. Curious, indeed, was the oft-repeated statements by senior Congress (I) leaders describing the Shiekh, after his death in September 1982, as “a secularist” and “highly progressive in outlook”. Equally curious was the statement by the leader of the State Congress (I) Legislature party, Maulvi Iftikhar Hussain Ansari, describing the Sheikh as “a communal politician sympathetic to Islamic fundamentalism”. Less than a month before the Sheikh’s death, Sheikh Tazamul Islam, President of the Jamait-i-Tulba, said that his party was being reorganised to bring about an Islamic revolution in Kashmir. In an interview published in “Arabia,” a journal published from London, Tajamul mentioned that, as part of the programme, students and youths were being trained and drilled for achieving “our goal of establishing an Islamic government in Kashmir.”

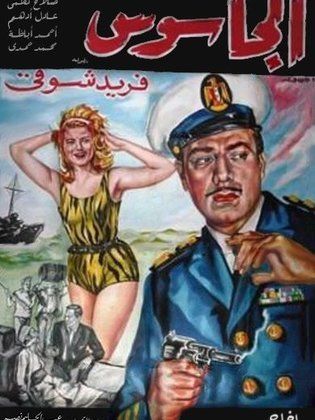

About a year after the Sheikh’s death, Jamait-i-Tulba and People’s League voiced the demand for acquiring arms for their workers and supporters. What for? Just to prevent “Hindu chauvinists” from attempts at doing away with the distinct identity of the Kashmiri Muslims. Before its merger with the Mahzi Azadi, the Muslim League had asked the Muslim youth to join “jehad” against secularism and for Islamic fundamentalism in Kashmir. The message was contained in a booklet in Urdu language circulated in Srinagar and elsewhere in the State. The 32-page booklet urged the Kashmiri Muslims to “prevent daughters of nation (Kashmiri nation) from moving around half-naked in educational institutions, offices, shops and public parks, to force closure of cinema houses and liquor shops, to eliminate narcotics like hashish which have fouled atmosphere in cities and towns and to revive your Islamic identity.” The booklet blamed outsiders (apparently meaning Indians) for attempts to “annihilate” Muslim religion and called upon Kashmiris to initiate a “struggle” against them.