|

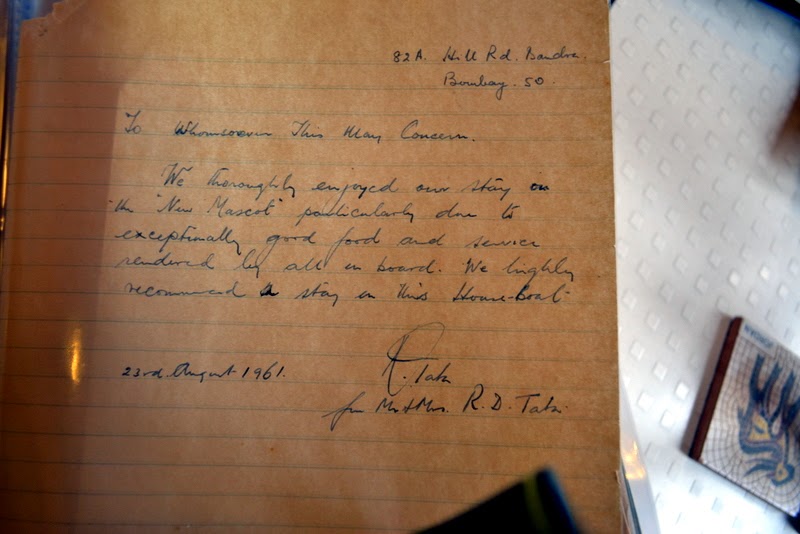

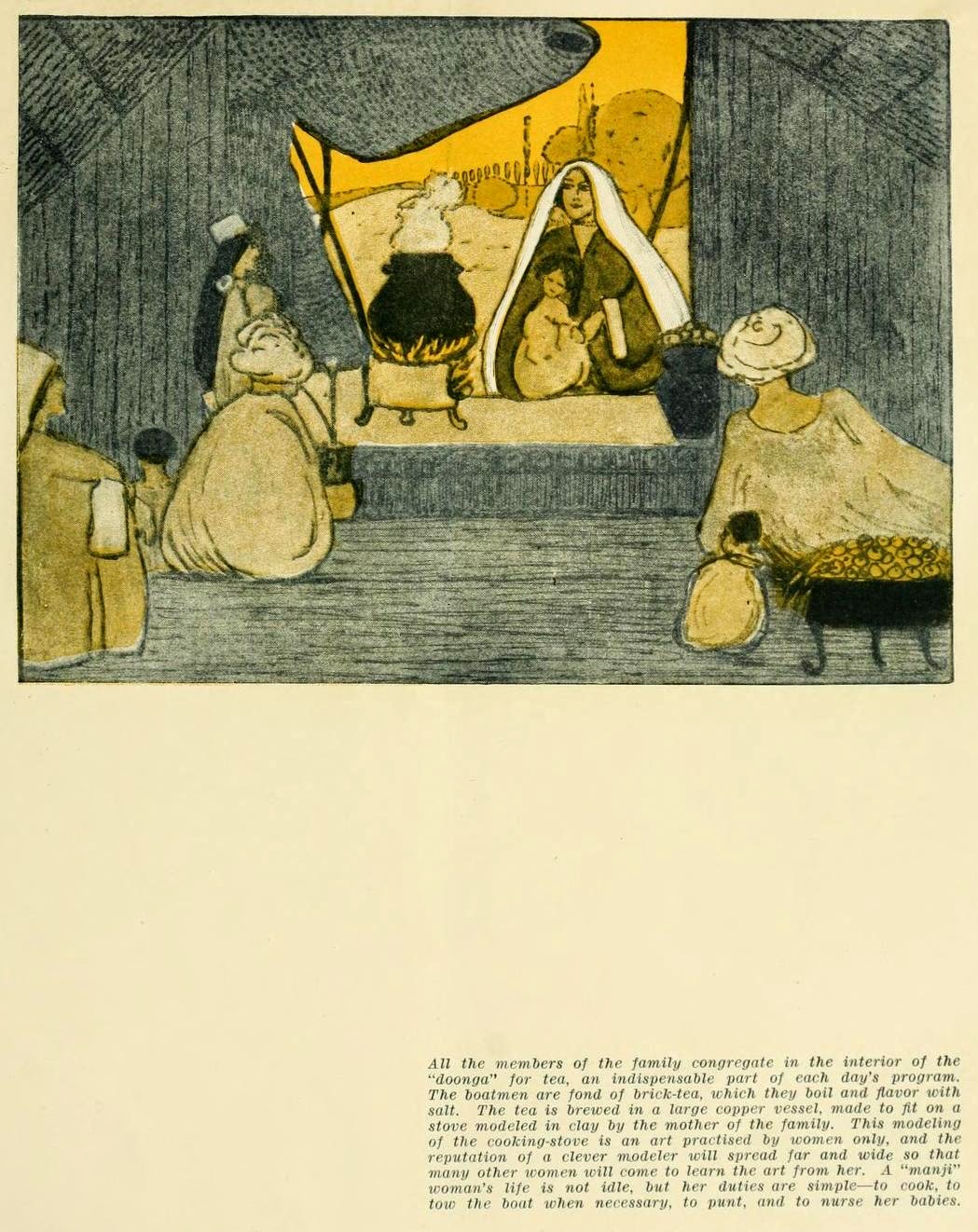

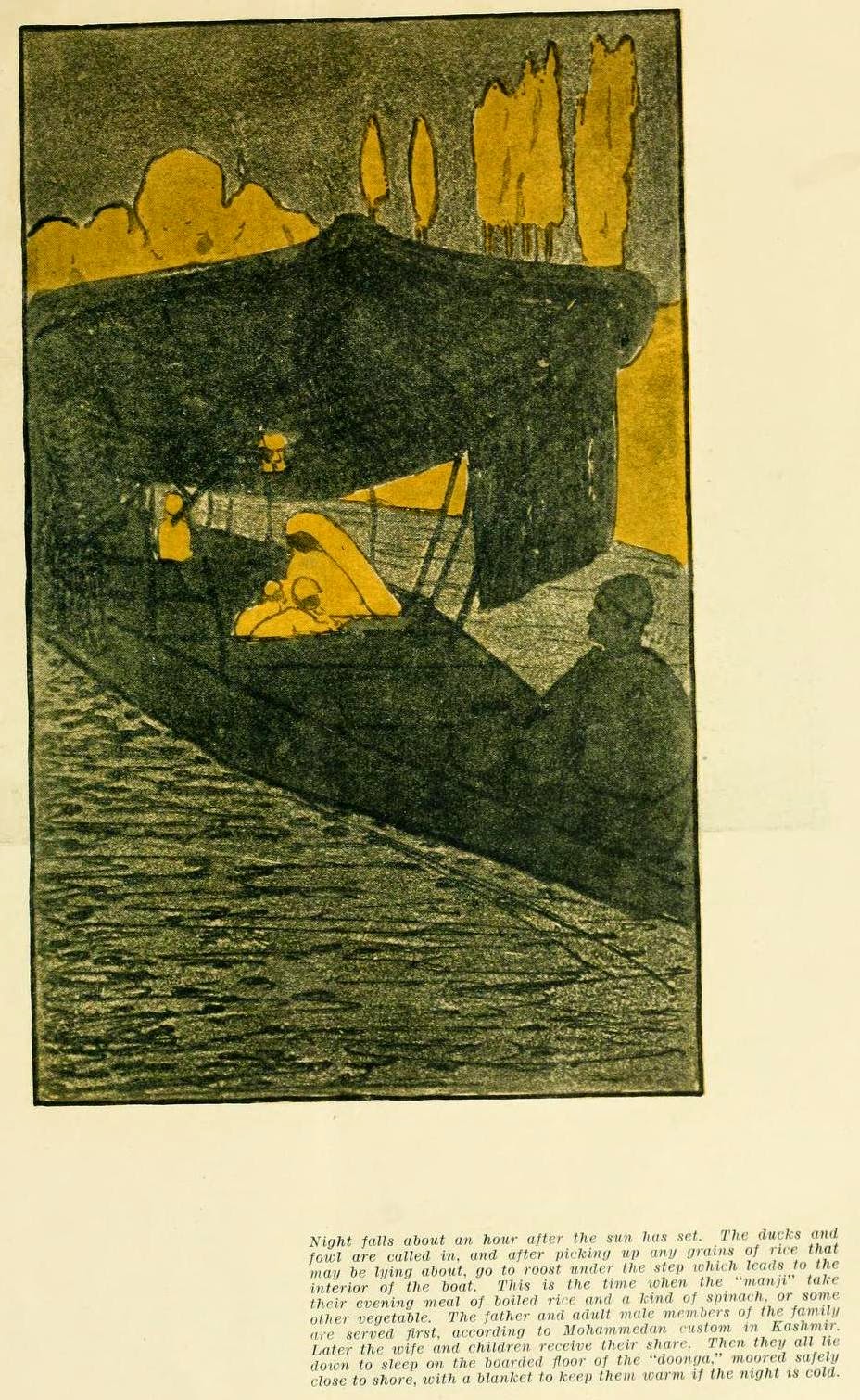

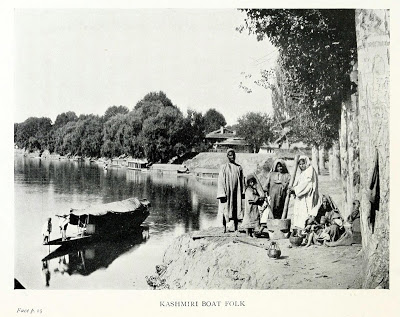

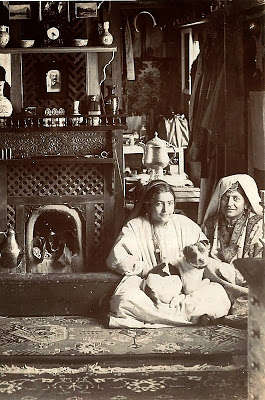

| Haji Family inside a Doonga 1918 |

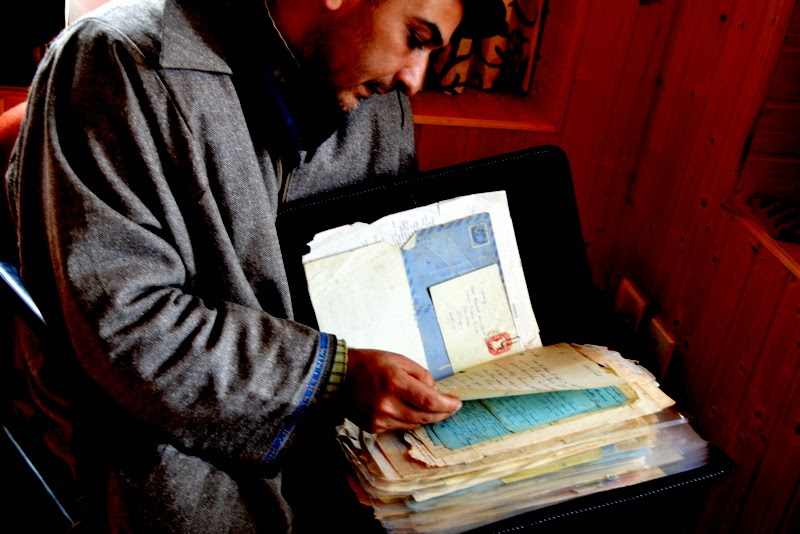

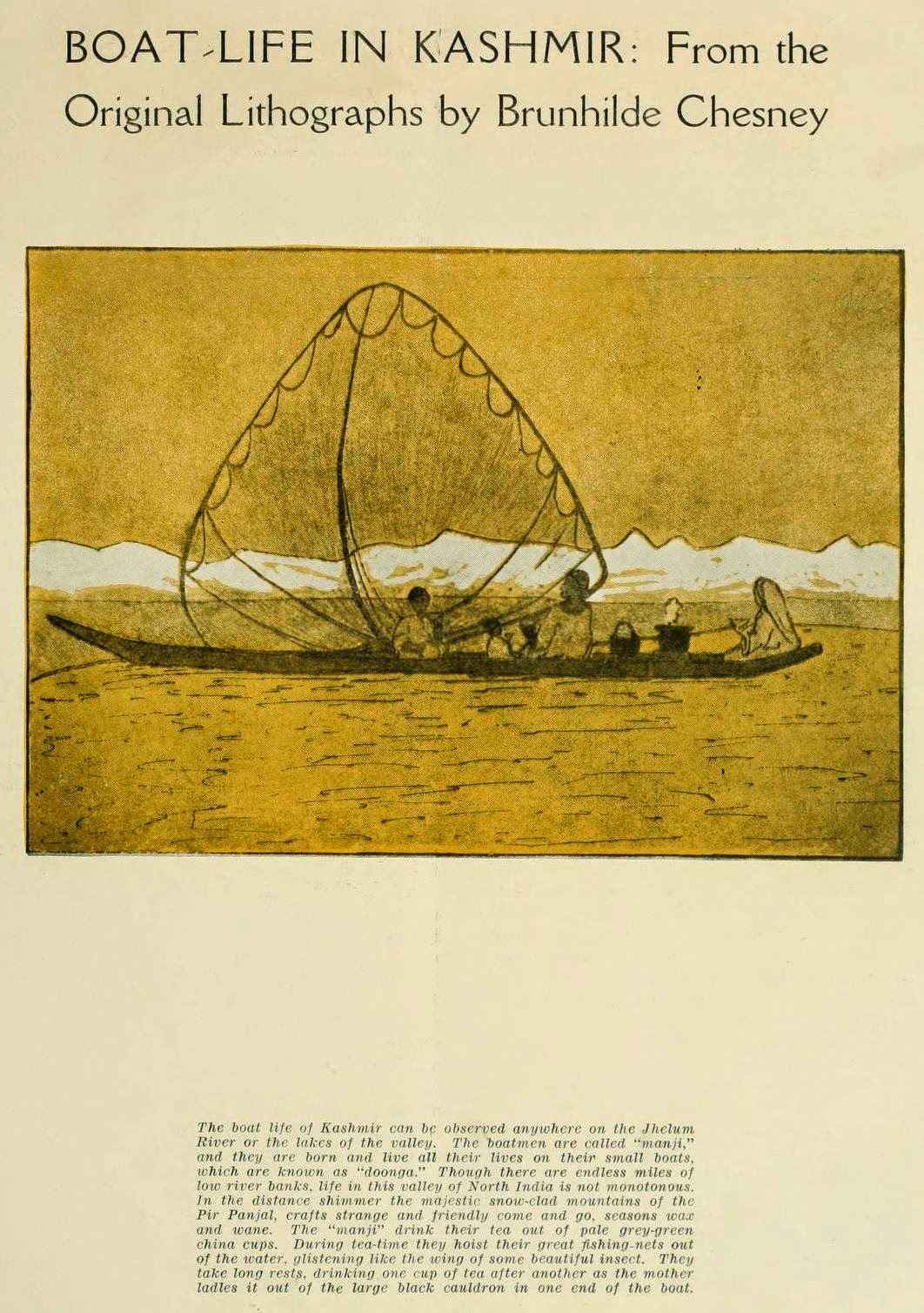

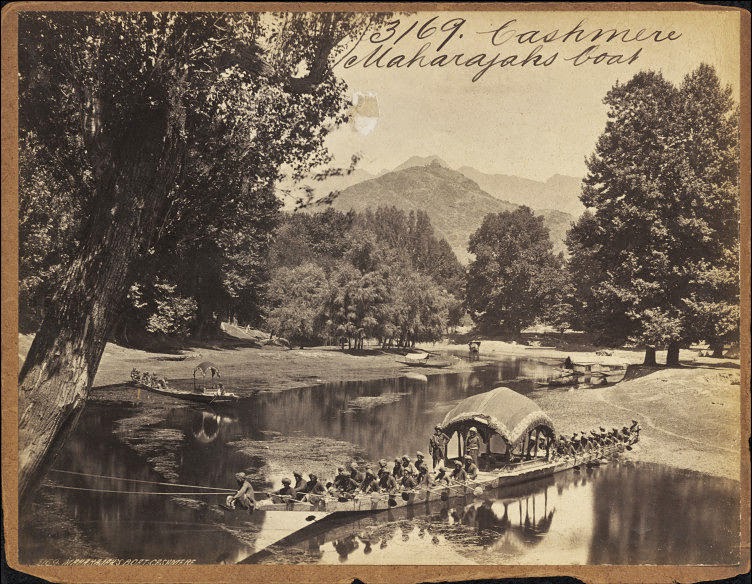

In Nilamata purana, the origin of Kashmir valley is told using the Matsya Avatar story. A great deluge, a divine boat of feminine power ferrying all life on the eternal waters of deathless eternal Shiva and this boat being rowed by Narayan in the form of a fish. The story conforms to the strain of Kashmir Shaivism in which female power Shakti brings about the experienced world to life through her interaction with Shiva. In this story half-human, half-fish Narayan is the rower. The doer. The action. The story is told in context of Naubandhana tirath, a mountain site near Kramasaras which we now know as Kausar nag located in the Pir Panjal Range in the Kulgam District’s Noorabad. The site where the divine boat was moored. The story is eerily similar to Abrahamic tale of Noah’s Arc and Jonah. Kashmir was born out of water. Myths as well geology tells us that much. The higher reaches of Kashmir mountains in fact have many sites where boulders have been carved by glacial action over millenniums to arrive at a shape in which a hole appears, a hole as if to tie a boat.

Where there are humans, where there is water, there exist boats, there exist stories.

| Matsya Avatar of Vishnu, ca 1870. Uttar Pradesh, India. |

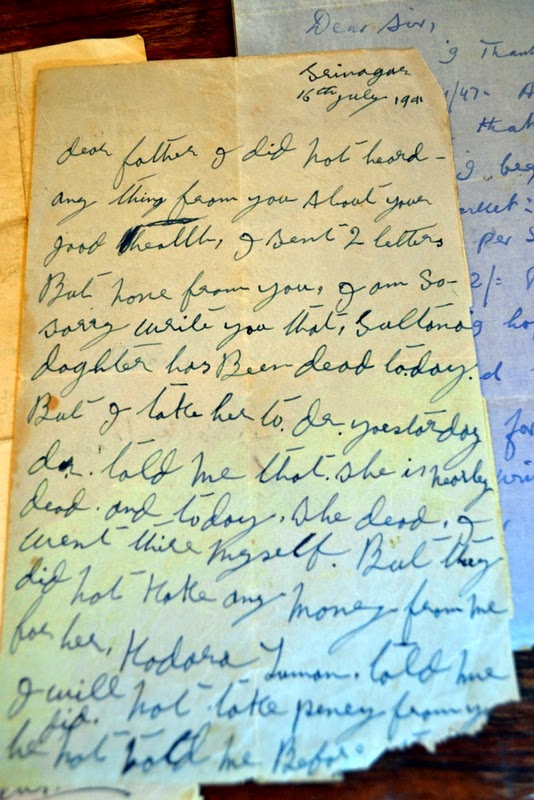

I heard the story of Kausarnag’s Naubandana many years ago from a Haenz, the tribe of people in Kashmir often called the descendants of Noah. While the ancient texts from Kashmir take pride in water origins of Kashmir, the people who actually made life possible in water filled land were not evoked much.

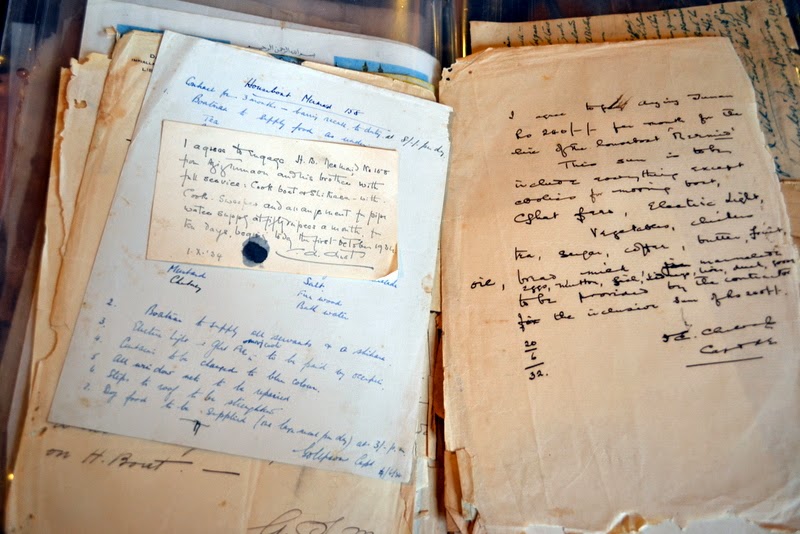

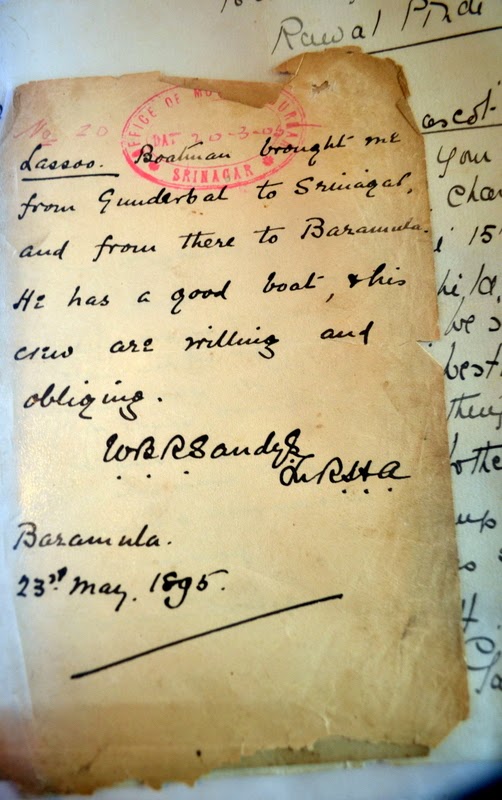

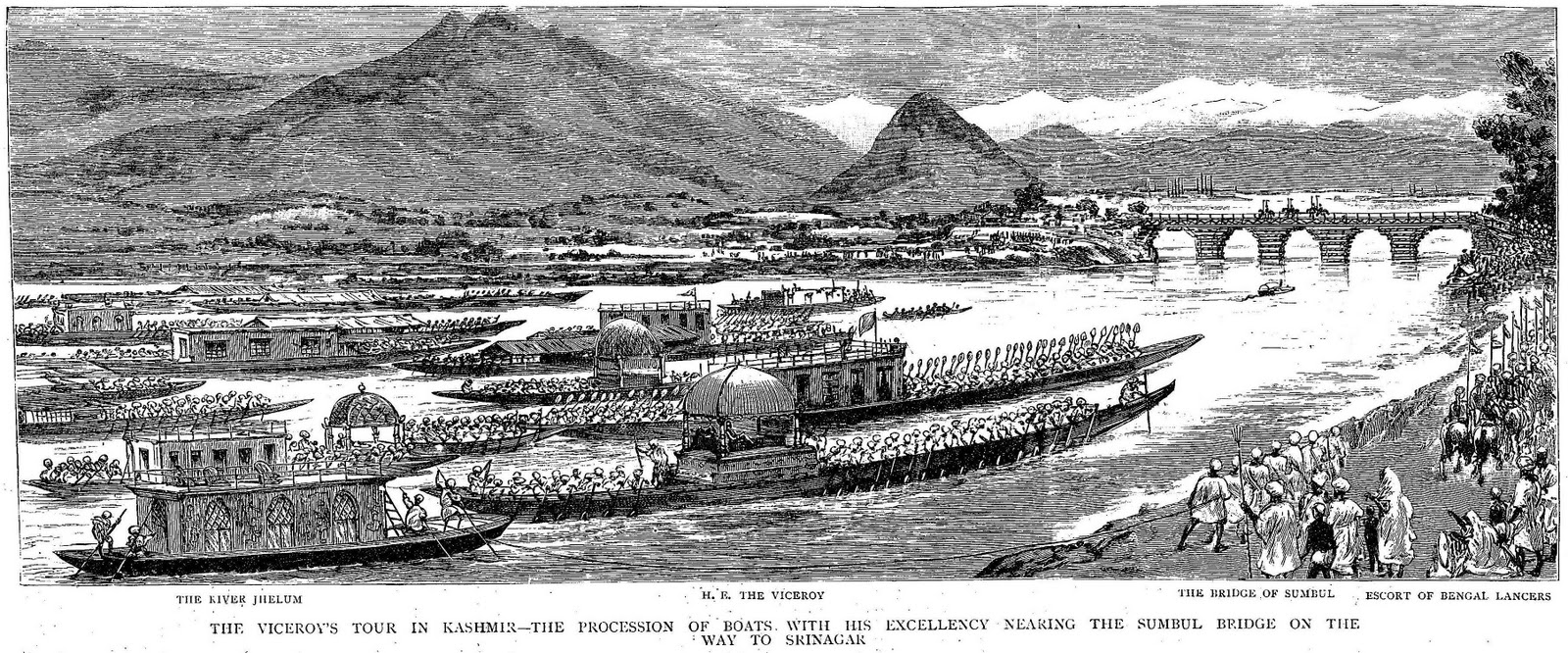

In Kalhana’s 12th century chronicle of Kashmir, Rajatarangini, we read about Nishadas, read about old trees along ancient canals, their aging trunks worn smooth by ropes meant for mooring boats. This is the only written testament to Boatmen’s existence in this ancient Kashmir. While history may have forgotten to mention Hanjis. The Hanjis didn’t forget History. For centuries they have been carrying with them oral history of changing geography of Kashmir, stories of cities being born and withering away, routes appearing and dissolving, water rising and falling, they have witnessed all that happened near and far from water bodies. It is thus not an accident that one of the of Rajatarangini’s authenticity as a historical work was provided by a boatman. In the 8th century, King Jayapida, grandson of Lalitaditya, called upon the engineers from Sri Lanka (in Rajatarangini, in typical Kashmiri manner, called “Rakshasas”) to build water reservoirs in Kashmir. Jayapida’s planned to build a water fort called Dvaravati (named after Krishna’s Dwarika). Alexander Cunningham, the 19th century British archaeologist identified Andarkut near Sumbal as Dvaravati. He was wrong and had only discovered half-a-city as the city was supposed to be built in two rings. A few years later George Buhler while looking for Sanskrit Manuscripts in Kashmir was rightly lead by a boatman to a nearby place called Bahirkut which he was able to identify due to its geography as Dvaravati. In this case it appears Brahmins had no immediate recollection of the place, but boatmen did. Sumbal was for centuries the major junction in water highway of Kashmir, it is natural boatmen knew the place more intimately. Interestingly, it is in an 8th century sculpture found in Devsar that we see the earliest model of a Kashmiri boat. The sculpture depicts five Matrikas, the protective mother goddesses being carried on a boat along with musicians. It is a boat procession, probably a representation of idol immersion scene, something still done in Bengal. Historical texts are bit descriptive about the type of boats in Kashmir and how they came into existence. Pravarasena II, late 6th century, can be considered the builder of Srinagar as the place of canals, bridges and water bodies, the way it is even seen now. He is also the builder of first boat-bridge in Srinagar, somewhere near the present Zaina Kadal. If the bridge was of boats, we can assume it was work of boatmen. Kalhana mentions many a boat journeys, however in his text not much is written about the people who made these journeys possible. There is a modern divisive theory popular in Kashmir that Hanjis were “imported” from Sri Lanka in Kashmir by an ancient King. Multiple books and experts mention it, often mentioning the name of the king as Parbat Sen and place named as Sangaldip. Writer G.M. Rabbani mentions that the King as Pravarasena II and the place as Singapore! Here lies the story of how colonial era writings shaped our modern understanding of Kashmir and how lack of further quality research and societal bias often made weapons out of them. The origin of this theory is a casual mention by Walter Roper Lawrence’s encyclopaedic work for future administrators of Kashmir, The Valley of Kashmir (1895). This work is still used as the primary source for what we now commonly know about Hanji. Lawrence’s primary (uncredited) source was ‘Tarikh-i- Hasan’ of Moulvi Ghulam Hasan Shah (1832-1898) written based on a lost work in Persian (complied out of older Sanskrit works) by Mula Ahmed, court poet of Zain-ul-abdin (1422-1474). The work (original ironically lost in a boating accident) is highly prone to mistakes as it seems a lot of meaning of original texts is lost in translation. The work even provides an alternate history of Dal Lake. King Pravarasena built a dam on Vitasta river at a place called Nawahpurah and made the river flow into his newly built city around Hari Parbat area. Then many decades later during the era of a King named Duralab Darun, there was a huge flood that lead to the creation of a lake which just kept getting bigger over the centuries. If we treat this work to be a source, we have to accept, Dal Lake is a man-made Lake and boatmen were again part of the endeavour. Still around Dal there are spots under water where you can see submerged temples, remnants of an older city, a place probably an experienced boatman of Dal can still take you to.

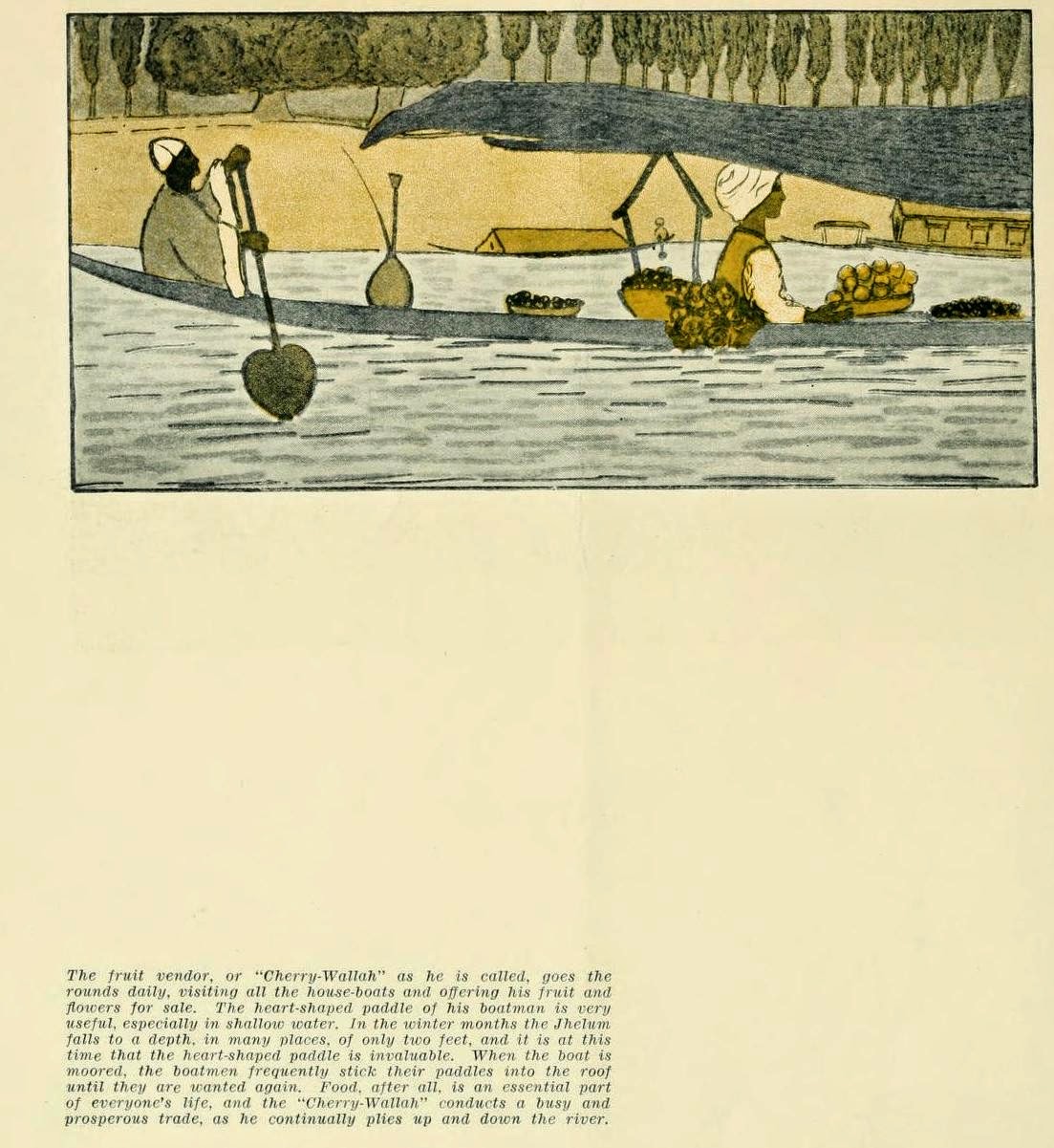

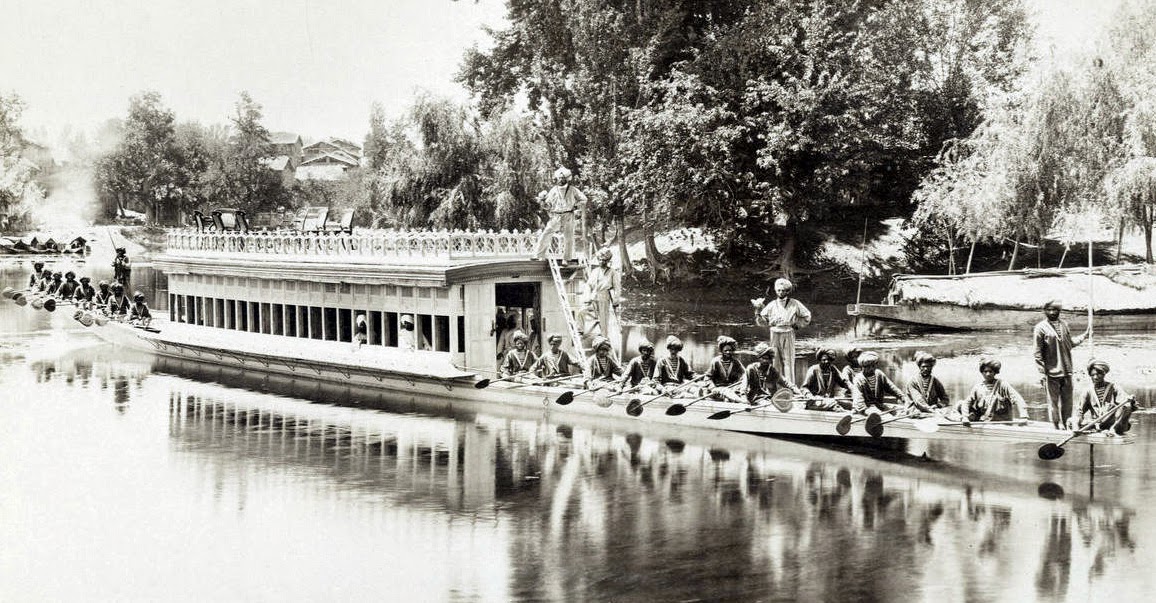

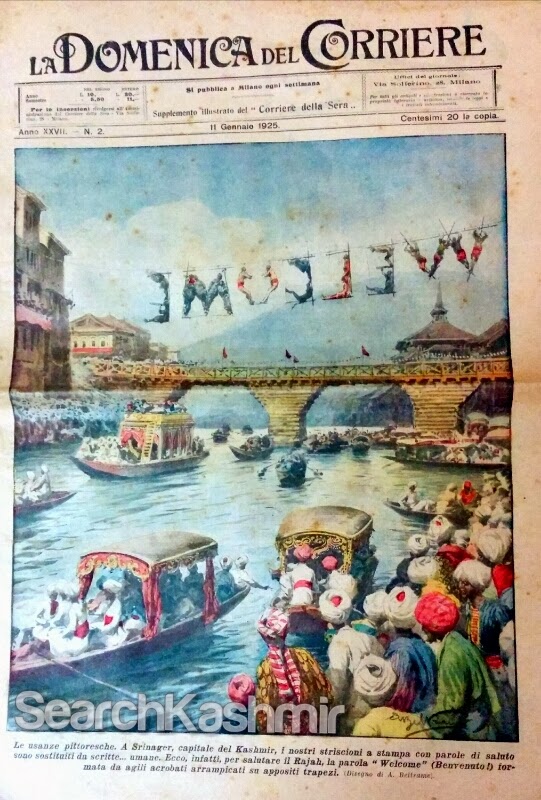

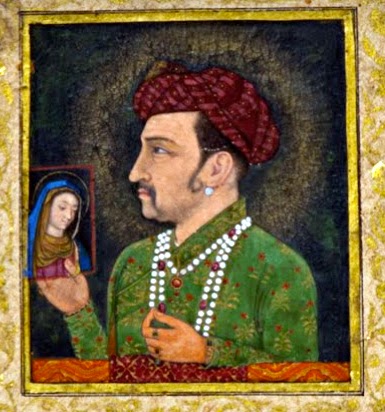

Many historical works point to the role played by Hanjis in shaping the ecology of the water-bodies, giving them the recognizable face we see today. In Srivara’s Zaina Rajatarangini, we find mention of “Dhivara“, the sanskrit term for fishermen used in Kathāsaritsāgara and Mahābhārata [“dhi” being iron…probably allusion to the iron harpoon used for fishing.] A few century later in Tarikh-i- Sayid Ali (1569) they are mentioned as “Koorjian” (?). The deep big lakes of Kashmir were unsafe for navigation for a very long time. Winds could build deadly waves in the lake. In ancient Kashmir, to make the lakes navigable, to break big waves from forming, islands were built in the lake, often these islands would also mark a temple. Sona Lank and Rop Lank of Dal Lake were for navigation of Dal. Most fascinating is the story of creation of Zaina Lank in Wular Lake, once the most feared lake of Kashmir. To build the Island, boatmen were employed by Zain-ul-abdin and they chose a site where there was a submerged temple, they knew this to be the perfect site. Baharistan-i-Shahi (1614) mentions Zaina got an architect named Duroodgiri from Gujarat to build him a boat shaped like ship with sails. The boat was used to build the Island that made Wular lake accessible to humans. It was boatmen who were hired to do it. This was also the boat that the famous King used for sailing on Kausar Nag listening to ancient works while visiting Naubandhana site. Knowing how deft the boatmen of Kashmir are in the art of storytelling, one can imagine boatmen regaling the King with miraculous tales about Naubandhana during the ride. Any tourist who has visited Kashmir would know this experience. Boatmen are surely the first guides of Kashmir. In this story we also see the appearance of a new technology in Kashmir, the sail boat. The makers of boat were over the centuries going to be an intimate part of this industrious tribe. In “Ain-e-Akbari” (16th-century) we read about the emperor wanting to build a houseboat: a boat modeled on the design of Zamindar house of Bengal, a two storied structure with many beautifully carved windows. For this he had many boats destroyed and then got an architect from Bengal to design his dream boat. It is said that thousands of such boats were made. These are the boats we see floating in lake bodies of Kashmir in Mughal paintings. Abu’l Fazl writes about Akbar’s visit, “this country there were more than 30,000 boats but none fit for the world’s lord, able artificers soon prepared river-palaces (Takht-i-Rawans), and made flower gardens on the surface of water.”

Hanjis were living in the simple doonga boats for centuries, calling it home. Yet, the term “Houseboat”, as we now understand in relation to tourism, can be assigned to this boat built on order of Akbar. We are still centuries away from the story of “Houseboats” as we see them today. In between we read about Aurangzeb’s attempt in around 1655 to build ships to compete with Europeans. Italians were sent to build the ship in waters of Kashmir. Two such ships were made but the experiment failed because the boatmen in Kashmir failed to get the hang of these foreign warships. Kashmiri boatmen in fact were essential part of Mughal Imperial Nawara Fleet or River Boat fleet. They were said to have played an important part in Akbar’s conquest of Bengal. In the last days of Mughal empire we read that Mughal river fleet comprised of mostly Kashmiri boatmen who would use their own language for calling out to each other and for navigating. Perhaps not so surprisingly boatmen also figure in King Lalitaditya’s conquest of Bengal in the 8th century.

|

| Ruler on a boat with attendants 17th century, reign of Jahangir British Museum In the background the island of Zain-ul-abdin (1422-1474) in Wular |

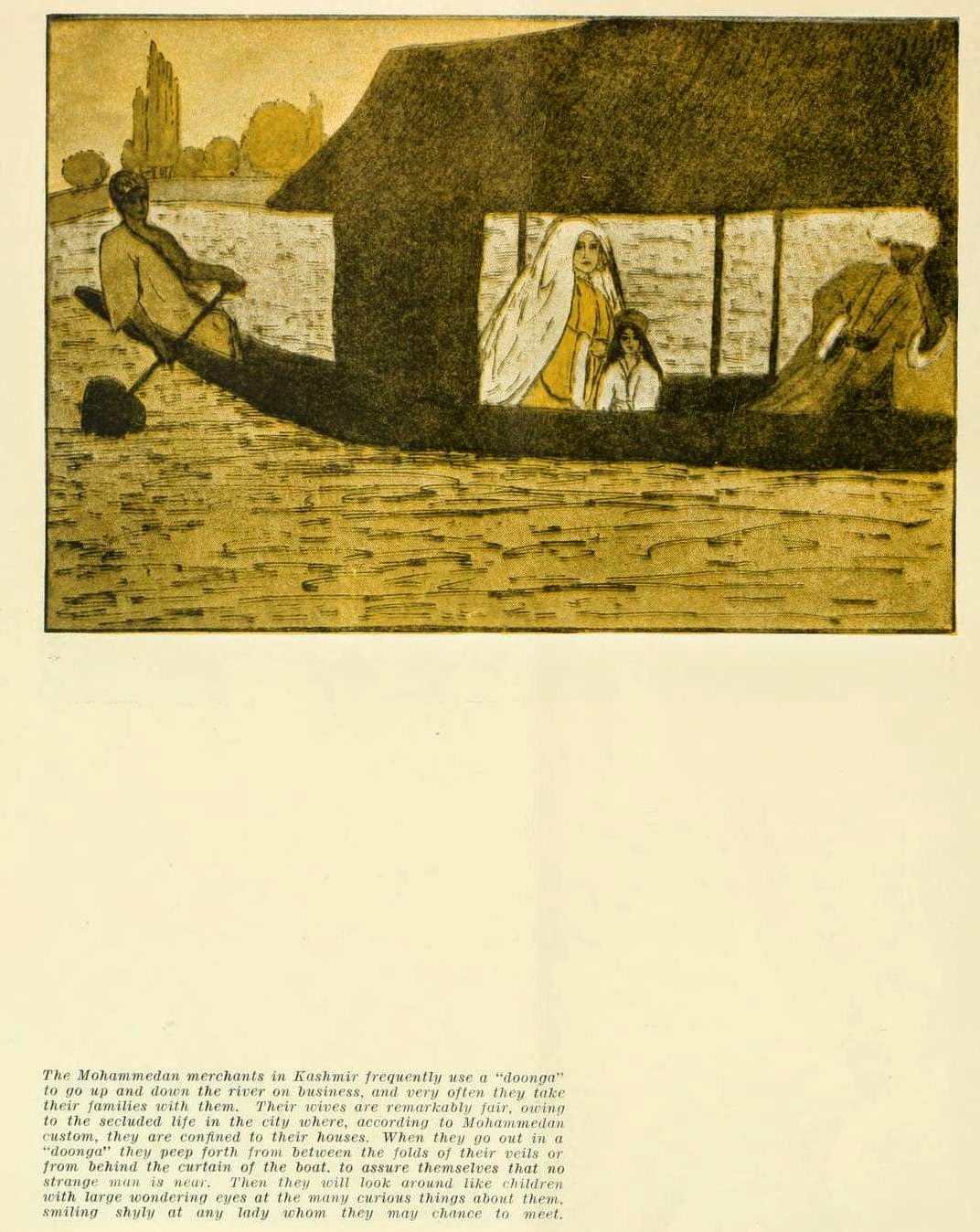

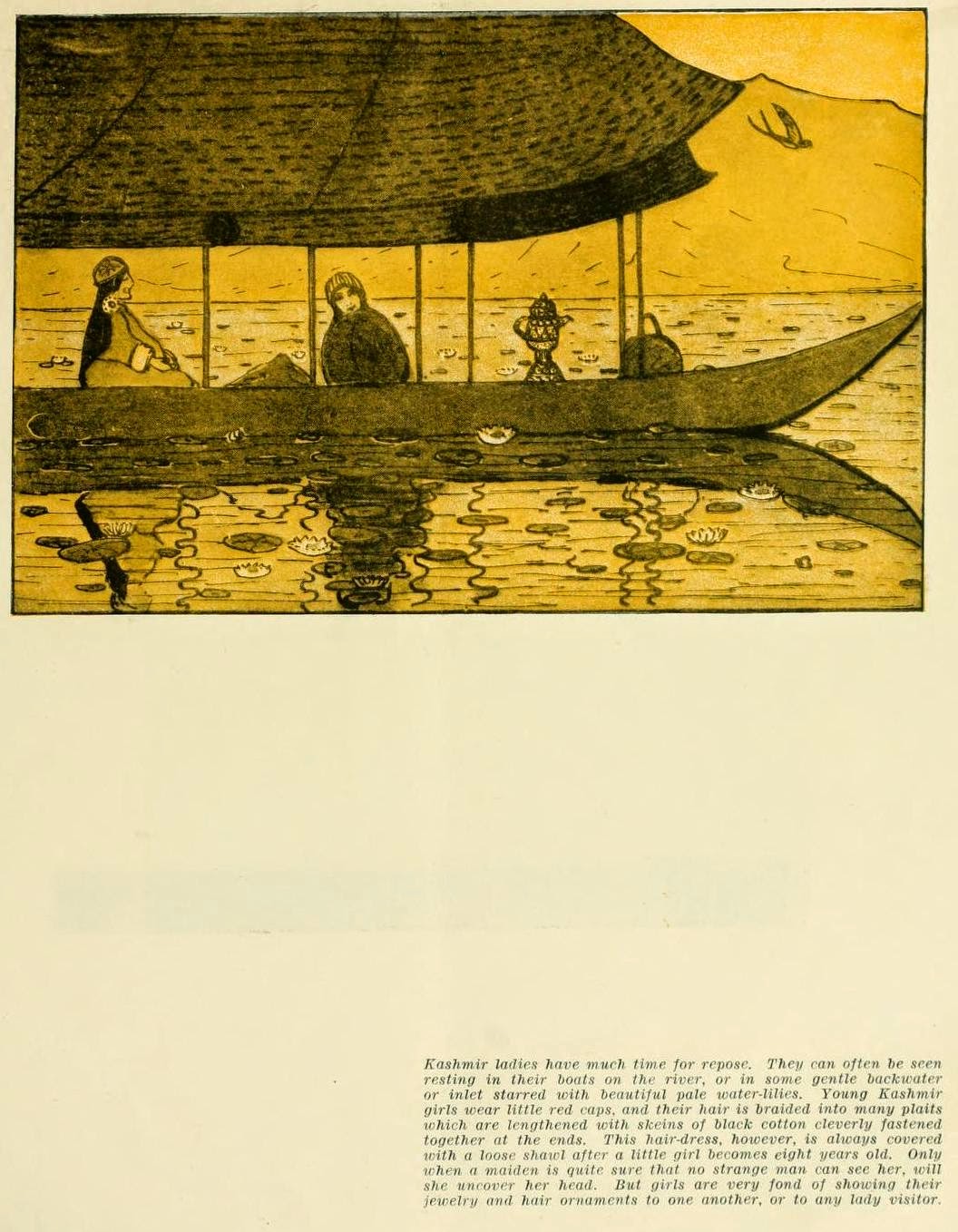

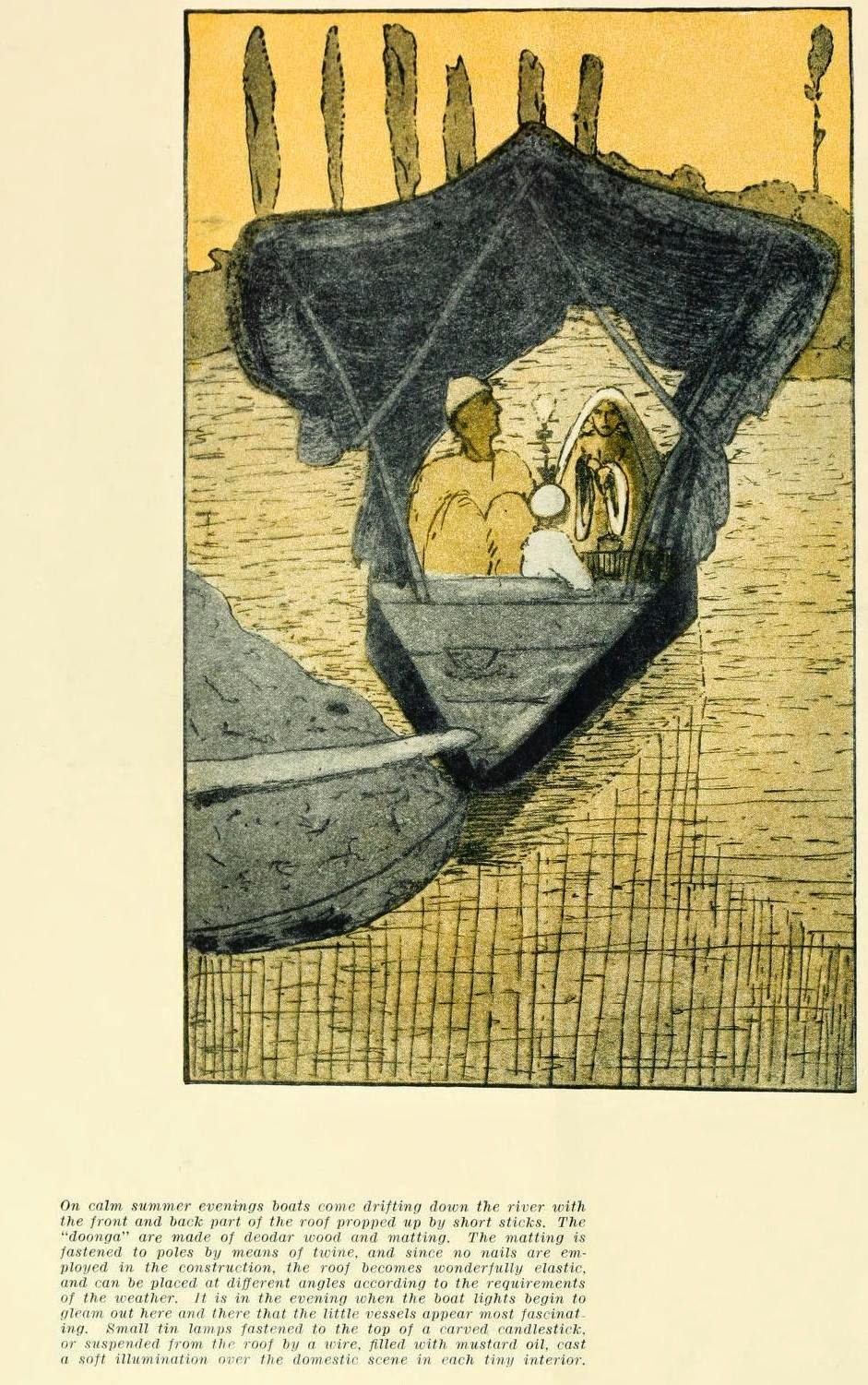

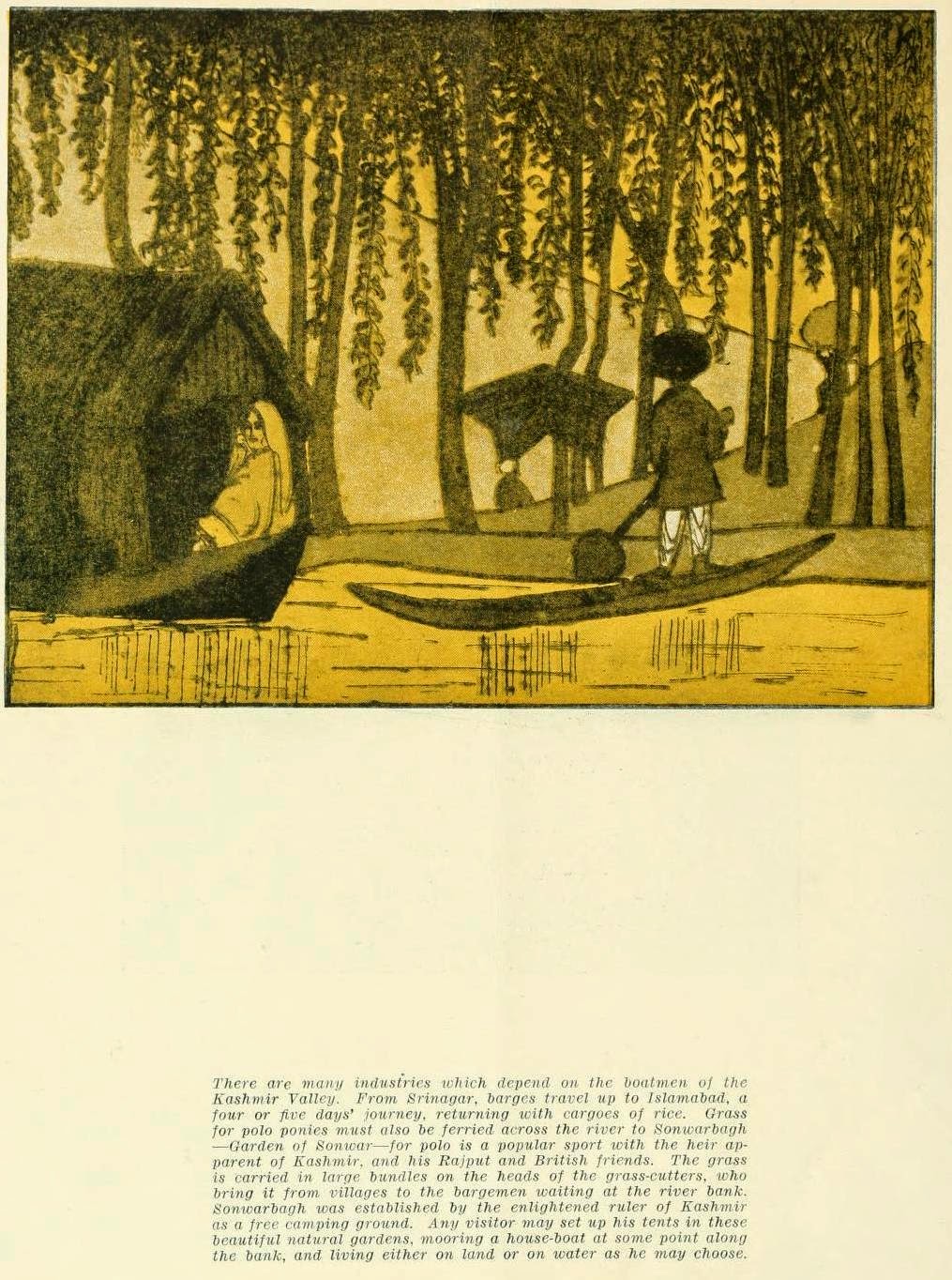

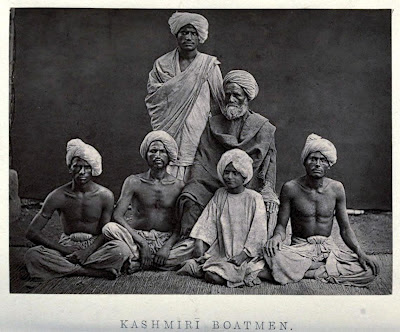

Meanwhile, boats in Kashmir were not for war, boatman was a trade involving life. Abu’l Fazl in his “Ain-e-Akbari” observes that life in Kashmir revolves around boats, they are everywhere. This was true even a few decades back. Food rations arrived in big “bahat” boats, material needed to build houses arrived in still bigger “War” boat. Fuel needed for cooking: “lobur” dung cakes were delivered by “Lobur Haenz” in “Khachu” boats. Utensils, vegetables, mats, milk and other essentials were delivered in a “Dembnav”. Water chestnuts (once a staple of Kashmiris, and an essential for Kashmiri Hindus on certain festive days) were provided by “Gari Haenz”. “Gaade Haenz” would get you the fish. Fishermen would catch fish in “Gadavari” boats, their families living on them under straw-mat canopy, keeping themselves warm using “manan”, a bare clay brazier, no Kangri. People and news travelled on fast moving Shikara, for longer journeys and pilgrimages there were Doongas. For crossing demonic waves of Wular, you could rely on “Tsatawar”, a small roofless small boats and your life would be in the hands of the most courageous and expert Hanjis. This was life in Kashmir animated by the boats and their engines – the boat people ever whizzing across the rivers, canals and lakes, like blood running through the veins, shedding sweat, pumping life.

|

|

|

One wonders who are these people?

|

|

|

The origin of Haenz the boatmen of Kashmir is shrouded in many tales. The term Haenz (Hanjis is Hindustani) itself is of uncertain origins. It today sounds similar to Manjhi of Hindustani. Certain experts now link Haenz to Sanskrit word “Navaj” for boatman. However, I propose a new theory: closest perhaps is the Sanskrit word “maṅginī”, used for boat and as well used for women. The wit of sanskrit word play in Matsya story thus comes to light. The word comes from “manga” for head of the boat. This word may well be the origin of ancient Kashmiri work “Henze” for women.

Why do we know so little about the people who were so essential to Kashmiri way of life?

Rajatarangini perhaps offers us a clue, or rather how this work approached history. Rajatarangini essentially dealt with the royal life, it was meant to be read by those besieged by the complexities of running a state. Thus, more often than not, only those people and tribes find way into it who in some manner, through their mobilization, at one time or another posed a challenge to the power balance of the state, or were thus essential to running the state machinery. Thus we find mention of tribes like Tantray, Margray, Dhars, Bhats, Kauls, Syeds etc. That not much is mentioned about Nishadas only means at no time did they pose a threat to the ruler, they were outside the scope of power. They had little time in their tough life for politics.

“The boats and boatmen of Kashmir” (1979) by Dr. Shanta Sanyal was first socio-economic study of Hanjis. In it the author makes a not so surprising observation about Hanjis and their approach to politics:

“As has been observed above, Hanjis or the boatmen, are a business community and their economic interests are the upper-most in their minds. The National Conference will also become a target of their criticism and open enmity if its leaders happen to place obstacles in the pursuit of their trade during the peak months of tourist season. The Hanjis expect every political party to behave during these months so that the tourists are not scared away from the valley. This means an economic disaster to the community and any party who helps this unfortunate situation is the nearest and the most Criminal Party in the eyes of Hanjis.”

Hanjis as a tribe is categorized as semi-nomadic, the people worked in various trades based on seasons (like growing vegetables, tourism, fishing etc.) and during other times, they worked as manual labor, often outside the state. The nature of this nomadic life meant education levels were low, they were unprepared for drastic changes sweeping across Kashmir. As some old ways of life changed, some associated professions started disappearing, thus today you will be hard pressed to find Lobur Haenz, cooking is now done by gas, Maer Haez gone with the death of Maer Canal in 70s, “War” and “Bahar” boat gone as trucks now perform the function, Shikaras are now mostly a tourist prop and Sumo taxis ply on roads like “Doongas” of yore. The people of Doongas meanwhile are stranded, relocated to land, minus boat, their economic well being fossilized, tied hastily to the question of aesthetics and environment. A community that has been undergoing massive disruptive changes to their way of life for centuries, is again, unseen, unheard being thrust under the wheel of history. There are some names buried even deeper in history. “Ayer Haenz” used to hunt and live in the forests. “Ayer” was the tribe in Kashmiri Ramayana to which the boatman King of Ganges who helped Rama cross the river. Colonial writers were to associate the tribe of the Ramayana hunter with Bhils, the largest tribal community of Kashmir.

Among the various tribal communities of India, Hanjis stand out in a unique way. Something happened in this community that seldom happens among other marginalized tribal communities of the county. A section of people in this community were able to take control of their economy, the capital and climb up the economic ladder on its own, purely based on grit, fortitude and some luck.

|

| Two Kashmiri Women with their Dog on a houseboat [late 19th century, probably by Bourne] |

How was houseboat born?

|

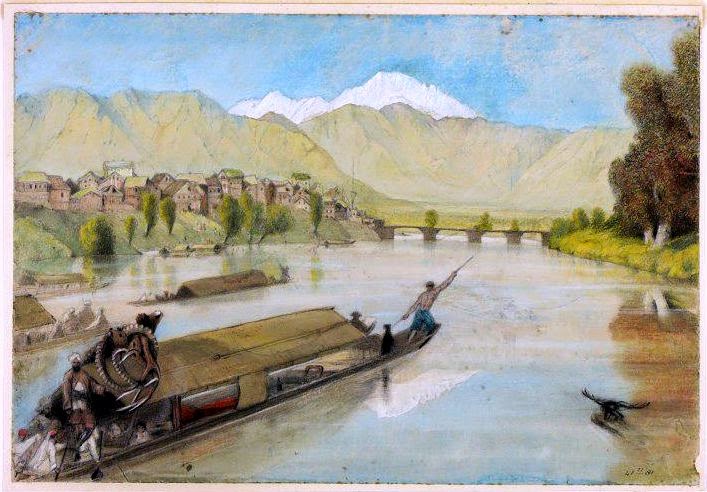

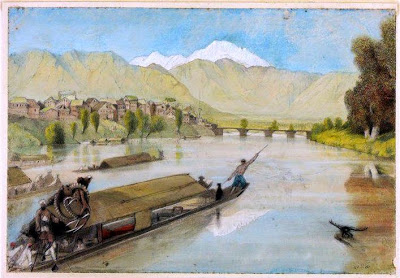

| Darpad Doonga George Landseer (1834–78) painted it in 1881 but depicts scene from 1860 when he accompanied Lord Canning, Governor-General of India from 1856-62, to Kashmir. |

Over the next few decades, there were spate of western travelogues and each of them singled out the houseboat experience as something unique. Boatmen became the wheels of tourism and with them moved many other industries that were dying. The great love of Kashmiri Shawls in West was over by the time Germany and France went to war in 1870, exports and sales were down. There was economic upheaval in shawl industry which lead to human upheaval. Ironically, only more wars in Europe helped Shawl industry survive. A surge in tourists was seen in Kashmir during the world wars. Western soldiers post in India, in Summers, for a moment of relief headed to Kashmir. They stayed in houseboats, purchased shawls and handicrafts as souvenirs. Earlier these specimens were sent to the west, now the west came to Kashmir. Kashmiri crafts were introduced afresh to the new world. A more direct case of houseboats leading to the economic growth of other crafts can be seen in case of Khatamband woodwork for ceilings. Lawrence notes, “A great impetus has been given to this industry by the builders of houseboats, and the darker colours of the walnut-wood have been mixed with the lighter shades of the pine.” The carpenters in this era picked up new skills even as old designs and motifs were used to embellish the Houseboat. The actual work of building the houseboat was pure native engineering applied to Deodar wood. Incidentally, Deodar wood was also essential to another great innovation of that era – Railways. The Railway sleepers in India were usually made of this tree wood. Tourism had a ripple effect on other crafts of the state too, for example: the tailors of Kashmir came to be known as some of the best weavers of English dresses. The birth of modern houseboat is one of the few genuine innovations driven by an entrepreneurial zeal. In modern lingo, we can say it was Kashmir’s “Silicon Valley” moment. And like in any true Capitalist system, the State had little to do with it in terms of capital investment or skill development, they were more involved in price regulations. It was people who drove the whole movement. It was driven by family of Hanjis who lived in Doongas towed at the back to Houseboats, people who served the customers, picked up new skills. Their service gave birth to the fabled concept of Kashmiri “mehmaanawazi” – noble service of the guest.

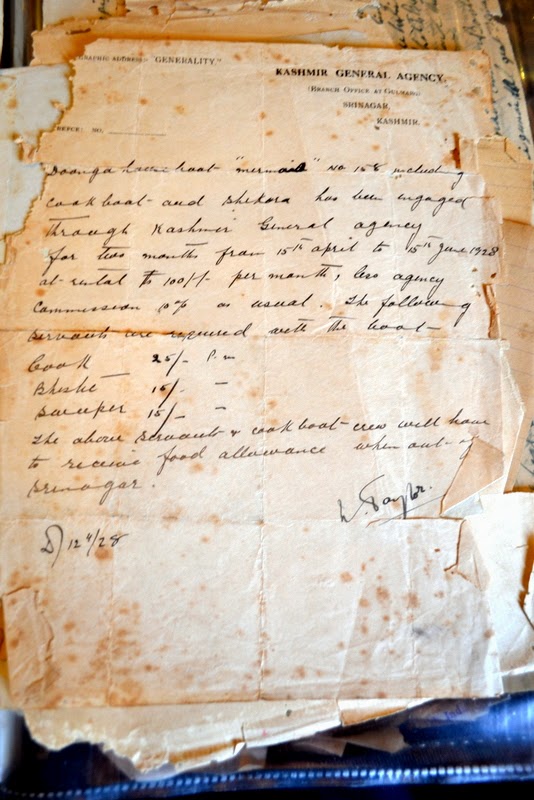

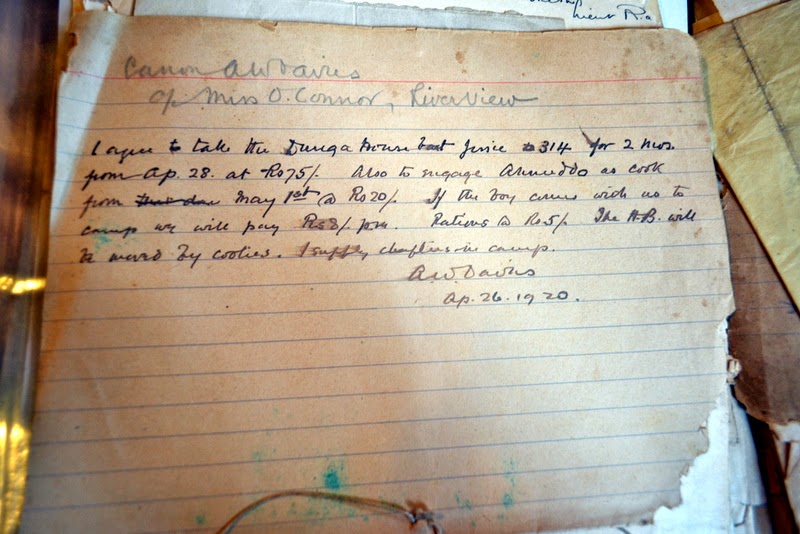

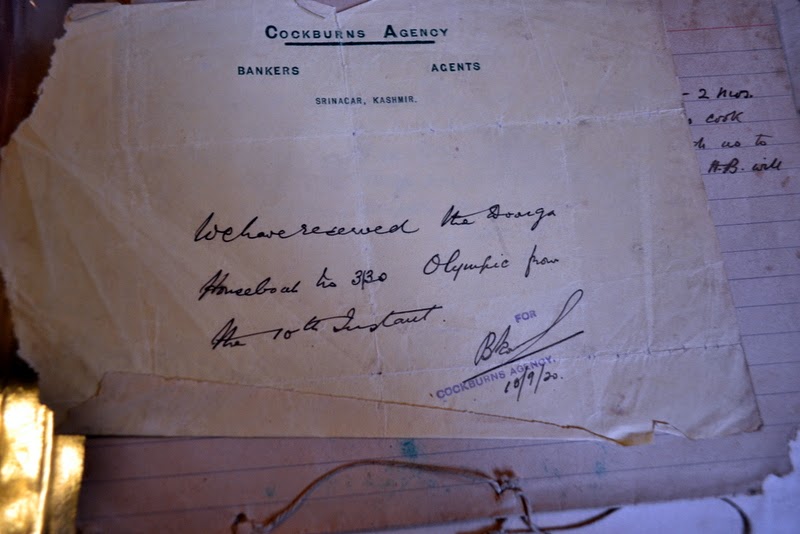

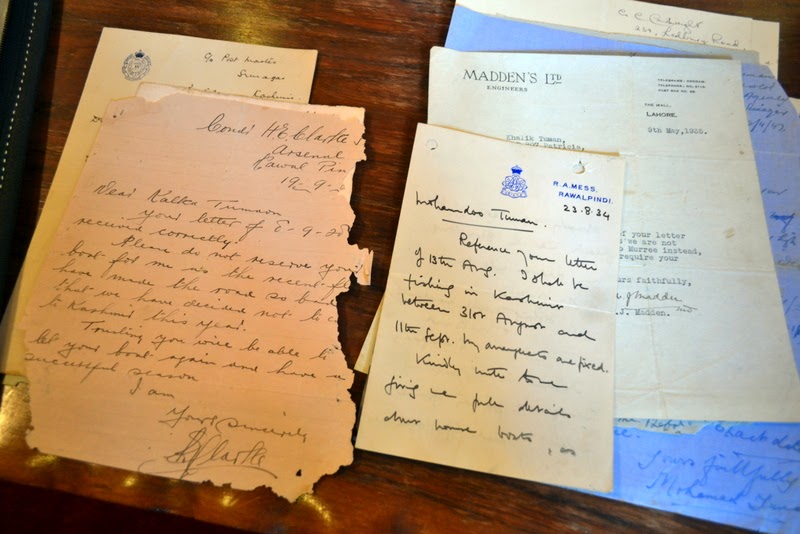

How did Kashmir come to have hundreds of Houseboats? Where was the Capital fund coming from?

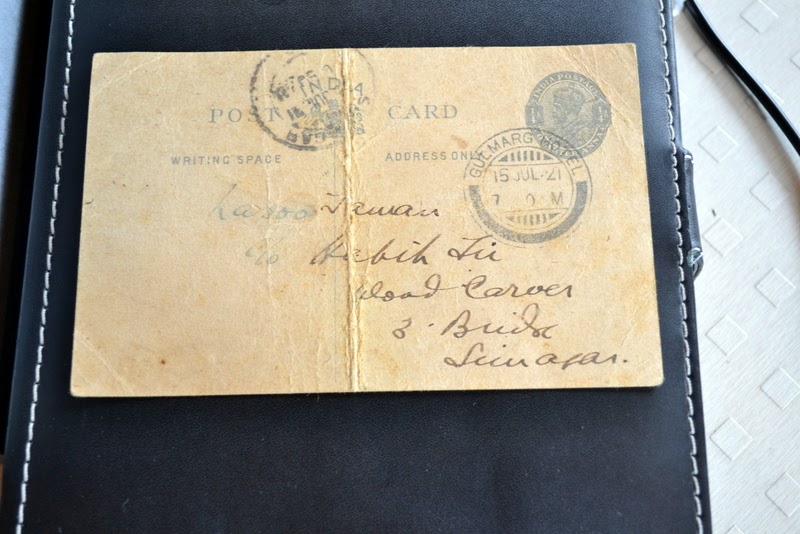

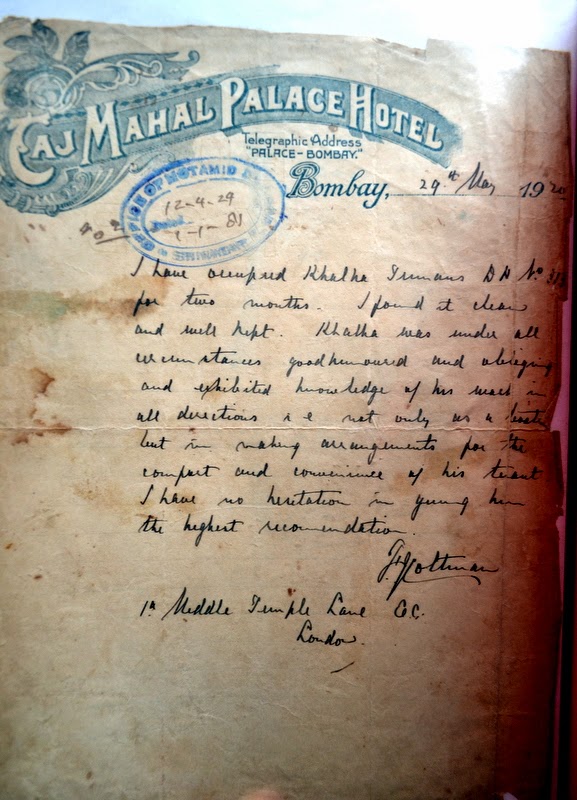

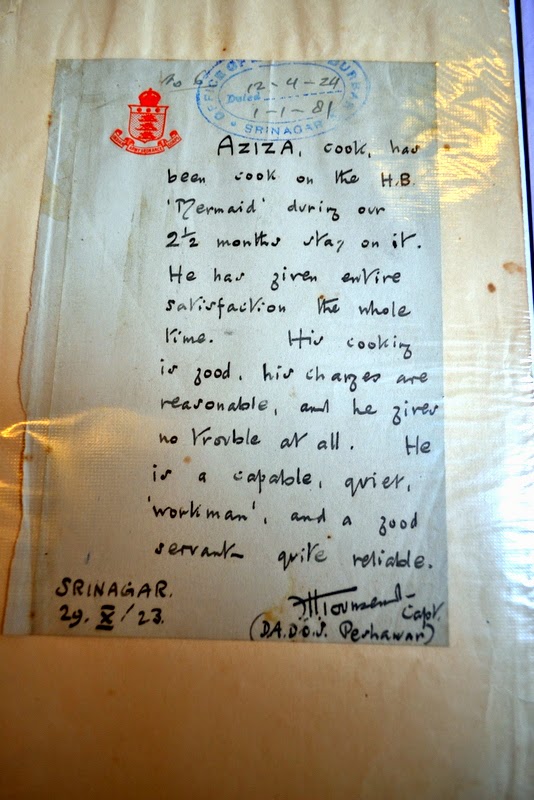

The story of houseboats in Kashmir is tied to a figure who one would assume had little to do with boats because of his caste. While Hanjis were learning a spatter of English language from tourists, picking up skills like making pancakes and Jams through corporal punishment at the hand of masters, Pandit Narain Das, a Kashmiri Pandit, was one of the first five Native Kashmiri to learn English (possibly again though use of corporal punishment) in a Christian Missionary School. In around 1885, Narain Das opened a shop for tourists which was destroyed in a fire incident. Narain Das moved his goods to a Doonga and thus started operating his shop from a boat. As business grew, he changed its straw matted walls and roof with wood planks and roofing shingles. The story among the Kashmiri pandit goes that Naraindas was soon approached by European tourists to purchase the boat. Naraindas sold his boat at a profit and soon realized that making and selling boats was a better business. He commissioned great many houseboats, an act for which he caught the moniker “Nav Narain”. P. N Madan, Director of Tourism for the State in early 60s however gives an alternative story to this beginning. According to him there was documented evidence to prove that a Gondola styled Houseboat was in fact commissioned in around 1880 by one General Thatcher. Since Thatcher did not know the local language, in order to pass orders to the builders, he used the English language services of a fourteen year old Pandit Nariandas. Thatcher stayed in the houseboat for the summer and at the end of the tour sold the houseboat to Narain Das for Rs. 200. That is how Narain Das got into the business of boat making. In oral history of boatmen, Narain Das is acknowledged as the man who put in money to get a houseboat constructed, then boats would be handed over to the Doonga Hanjis, in return the Hanjis would pay him a “cess” on services rendered to a tourist. In modern terms he would be called the “venture capitalist” of the industry. Thus in 1906, the number of houseboats in the valley was already in hundreds.Till the year 1948, Narain Das’s family alone had built and managed some 300 houseboats. This golden era of tourism came to an end with the India-Pakistan war of 1947-48. The main benefactors and regular clients of the industry, the British were gone from the sub-continent, new tourists were afraid to travel to a conflict region.

|

| View around Shah Hamadan by William Carpenter Junior, 1854-55 |

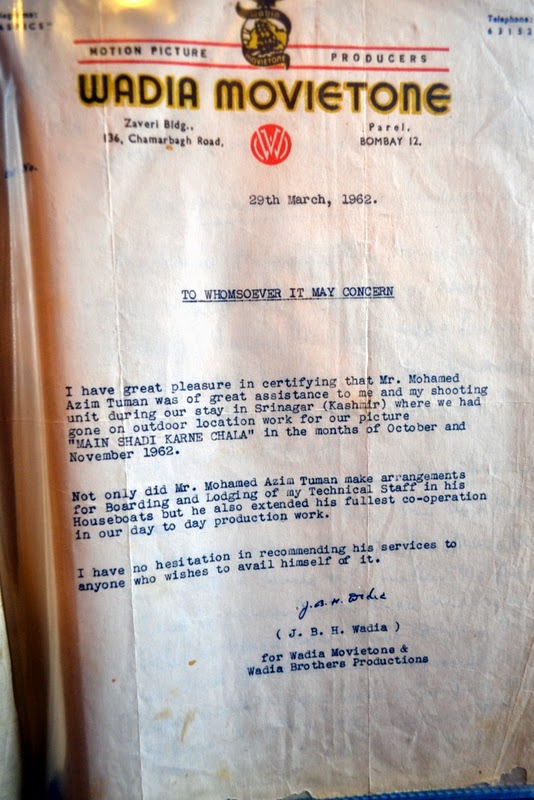

In 1948, only about 5000 tourists stayed in houseboats. In 1950, the total number of tourists was 7000. Hanjis remember the 50s as the terrible decade when houseboats were dismantled by the owners to sell prized deodar wood as a means of sustenance. To relive Kashmir’s economy, it was obvious that tourism had to be revived. In 1948, not many tourists may have arrived, but certain interesting people from artist community arrived to revive the magic of Kashmir on people’s mind. S.H. Raza the world famous painter arrived and stayed on a houseboat in Jhelum near Bund. The houseboat became a hub for budding artists of Kashmir who would watch him paint and out of these artists came the artists who started the Progressive art movement of Kashmir. Early art exhibitions were held on houseboats, so the houseboats became an art studio. Central government commissioned documentaries on Kashmir prominently featuring the boat life. Anthropologists, sociologists, photographers and journalists arrived to document the life of water people. Houseboat owners, dug into their carefully maintained guestbooks going back a century and reached out to old patrons and invited them back. There were ads in international magazines selling the royal dream of a houseboat. “Jash” cultural boat rides were organized in Kashmir. Slowly the tide was turning, the image of Kashmir as the “venice of east” was re-established. Improvements in film photography technology meant Cinema repainted the old monotone descriptive images of earthly paradise in vivid and lush technicolor. Few mortals could ignore the lure. Tourists rediscovered Kashmir. Some Raj era tourists agencies also survived, meanwhile agencies like Razdan, Mercury, Sita etc arrived on scene. As we shall see, while tourism revived, the lot of Hanjis did not change much even as tourists were drawn to Kashmir because of them. For fishermen Hanjis, new varieties of fish were introduced which marginally improved their lot, rest were on their own, working as seasonal manual labor. Till 1979, 87% of Hanjis still lived on boats, only 2% had “pucca” house, 55% lived below the poverty line, only 40% could be called literate with only 2% having finished intermediate standard and still more alarmingly about 60% of Hanjis were under one or another form of debt. We are here talking about a population of two Lakh sixty thousand Hanjis. There were 403 houseboats in the valley at the time and just about 500 Shikara taxis for tourists.

In around 1978, Clarion advertising agency of Calcutta gave the tourism department of Jammu & Kashmir State its symbol – a Shikara on a lake against the background of a mountain. This was the beginning of the second golden era of Kashmiri tourism again driven by boat. By 1981, this number of tourists was to become 6 lakh, while the total houseboats were about 740. Post 1947, number of houseboats in Kashmir reached its zenith in 1985-86 with 825 houseboats. Old houseboats were restored and new ones built in anticipation of even greater numbers. As tourism grew, government policy changed and curtailment was done on number of houseboats. This despite the fact that if Kashmir tourism reaches its full potential, even these number houseboats are not enough as quality tourists do prefer the houseboats. Concerns about the impact of pollution, encroachment of water bodies were being raised, all ignoring the rapid urbanization on land, the blame was squarely put on the boatmen. All these issues came to a stand still along with tourism when the violence of 90s broke out. It was a shock from which boatmen community is still reeling under. Only a trickle of tourists arrived in Kashmir, that too post-1993 when Hanji community on its own stepped out to personally get the tourists. Besides big Indian cities, the went to cities in Europe and far-east countries like Taiwan, Hongkong, Malayasia and Thailand. They worked hard to put the fear of violence out of the visitors, it was tough, but few did come, and all the other tourism related trades benefited from these efforts. It was during these years that the houseboats on Jhelum went into a state where the owners could not afford to repair them. People in Kashmir started to think of these icons of Kashmiri craft and culture as eyesore. Something that needs to be hidden away like a piece of old furniture.

Fall of tourism in Kashmir in the 1990s, also saw the rise of tourism in Kerala which too has a great boat culture. The place celebrates it. Kerala people take pride in their houseboats as they claim their Kettuvallam (rice barge) boats to be many millennia old. Still, such was hold of Kashmir over the minds of tourists that in Kerala, boatmen came up with motorized boats and named them “Shikara” to dazzle the visitors. It is ironic that icon of Kerala tourist is a tree, a coconut tree but boatmen community is thriving, meanwhile icon of Kashmir tourism is a boat, a shikara but boatmen are seen as some sort of foreign intruders out to destroy environment.

|

| View around Shah Hamadan, February, 2014 “beautified” sans houseboats and boat people |

Yet, in the 2000s when Kashmir again was to be revived from economic slumber, tourism was the vehicle, boatmen were again asked to row the massive ship. Again, the cycle of 50s-60s was repeated. Shikara again was brandished as the mascot of tourism, magic of cinema invoked, articles were written, advertisements published, old patrons sought back, slowly the tide again changed. One can actually map the fate of tourism in Kashmir with the number of houseboats on water. In the year 2000, there were 850 houseboats in Kashmir, which in 2007 grew to 1000. Number of tourists about 5 lakh, bulk of them domestic. Once tourism showed signs of revival, again new measures were put in place to curtail the number of houseboats in one way or another. It is almost a pattern. Use boatmen to kickstart the engine of tourism, when efforts start paying dividends, try to side-step the Hanjis by invoking environmental concerns. Here one needs to ask who is better posed to take care of water bodies, a community that have lived in them for generations or people who can’t tell a lake from a pond? World over, for success in saving the environment, local native tribes are made a party to the effort, a synergy is developed, a collaborative effort is taken in which the first step is recognizing their right to the resource and environment, an ownership is established. There is no other way as 80% of the world’s biodiversity is in tribal territories. There are environmental movements that seek to decolonize the approach to conservation. However, in Kashmir Hanjis are being denied the claim that they actually have a territory.

In all this, it must be remembered that post 1947, Hanjis as people were directly or indirectly under the control of Tourism department. That must be unique example for a tribal community anywhere in the world. Their fate was all the more tied to tourism. If tomorrow it was deemed that Hanjis are not essential for tourism, or if it is deemed they are detrimental to the environment in which they have lived for centuries and are better equipped to care about, then truly the future of this tribe is bleak. Dispersed all across the valley, dislocated from their centuries old trades, low education levels, with no ability to put an elected representative in the state assembly, they are disenfranchised people living on whims and fancies of seasonal environmentalists, bureaucrats, judiciary and the government. Thus is ignored the simple fact that Dal probably is shrinking because of effluents coming in from modern townships like Hyderpora, urbanization around Nishat, the development happening on land all around the water body, increasing sedimentation around the edges and also increasing aquatic weeds in the Lake, thereby destroying the endemic biodiversity. Why isn’t this obvious reason first dealt with?

Without prioritizing needs of the people directly impacted by drastic change in government policies, without gauging the reason of failure of previous government schemes supposedly for the benefit of Hanjis and environments, without factoring in the rampant bureaucratic corruption and power lobbies at work, putting boat people on land is like putting a fish out of water (in the name of fish and water) and expecting it to learn to walk.

|

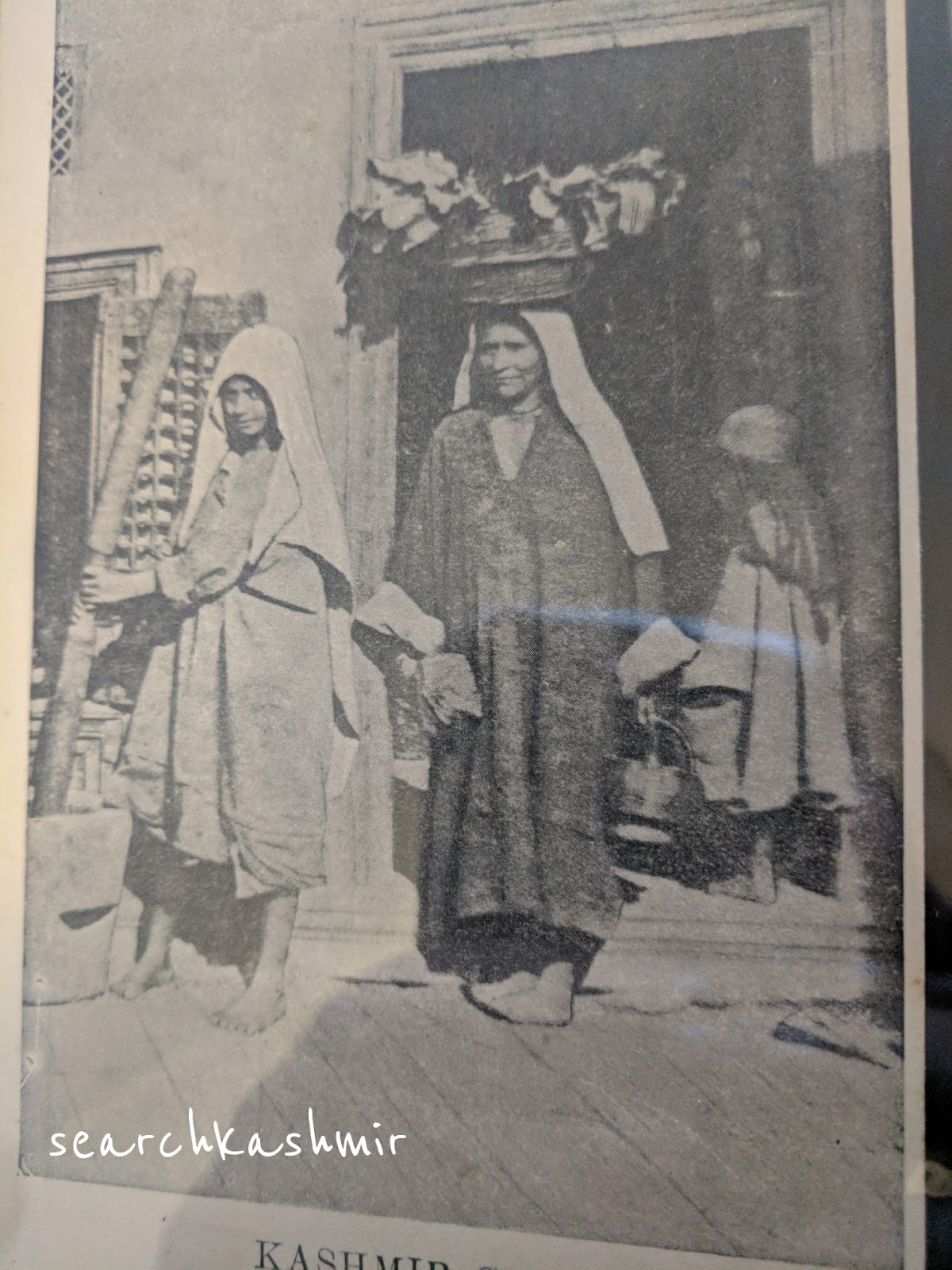

| Hakh/Vegetable seller. Postcard from circa 1930s |

We need to acknowledge that we are talking about the lives of an almost invisible marginalized aboriginal tribe. “Haenz” the word is as old as the Kashmiri language. In sayings of Lal Ded (14th century) we find reference to Haenz lady of Anchar lake, selling lotus stem, calling out to potential buyers. Lal Ded hears her calls and has a moment of epiphany as she engages in a dialogue with the lady. Lad Ded, the grandmother of Kashmiri language and culture, manages to find divine message in business call of a Haenz woman. Lal Ded heard the voice of people whose “coarse” language has been derided by civilized society for centuries. Lal Ded’s ears were open to her calls, her eyes registered their presence. Only then could she sing:

Aanchaari Hanzeni hund gom kanan

Nadur chu te hyayu maa

Ti booz trukyav tim rude wanan,

tsainnun chu te tsinev maa

Call of Haenz lady of Anchaar fell in my ears

“This Nadru, who would buy?”

Hear this the wise exclaimed:

“Dwell deeper, would you dwell a bit deeper?”

It was only post 1947 that someone heard this call. Dinanath Nadim, the progressive poet in 1950s wrote a song on this exact Vakh of Lal Ded using the refrain of Haenz women’s “hyayu maa”. Yet, the real call remains unheard, the tribe still struggles against a tide.