Something I always wanted to do: Visit a historic site in Kashmir that I had read a lot about and seen a lot of vintage photographs of. Done.

About 28 kilometers southeast of Srinagar, on the right bank of upriver Jhelum, on the main road to Bijbehara, are located the ruins that mark the Awantiswamin Temple. Travelling by road to Kashmir, this is the first major historic site that one gets to see. The place is know as Vantipor or Avantipor and was founded by King Avantivarman (AD 855 – 883 AD), the first king of the Utpala dynasty, on the ancient site called Visvaikasara.

The first mention of these ruins in old western travelogues can be found in George Forster writing about his visit to the place in 1783 although he identified it as Bhyteenpur. Then in writing of Moorcroft who visited the place in 1823, Baron Hugel in around 1835 , Vigne in around 1837. All of them saw a confusing mass of stones hinting at remains of ancient ruins buried under ground.

Alexander Cunningham in about 1848 took the first serious look at the ruins, did some basic digging, exposing remains of a bigger structure. Even though a lot his assumptions were proved to be wrong (like his assertion that the temple must have been dedicated to Shiva and the size of the temple).

The scene was recored for posterity by John Burke in 1868 and presented in Henry Hardy Cole’s Archaeological Survey of India report, ‘Illustrations of Ancient Buildings in Kashmir’ (1869).

|

| Photo1: Burke’s photograph from 1868 |

The first serious excavation work at Avantipur began at a cost of about 5000 rupees in 1910 under J. C. Chatterji on recommendation of Sir John Marshall to the state Durbar in 1907. His digging went to no more than 7 feet below ground level i.e. about 8 feet about the courtyard floor level of the temple. Chatterji found some copper coins and charred remains of a birch-bark manuscript. The floor, several stairs, central shrine and the basement of peristyle remained buried.

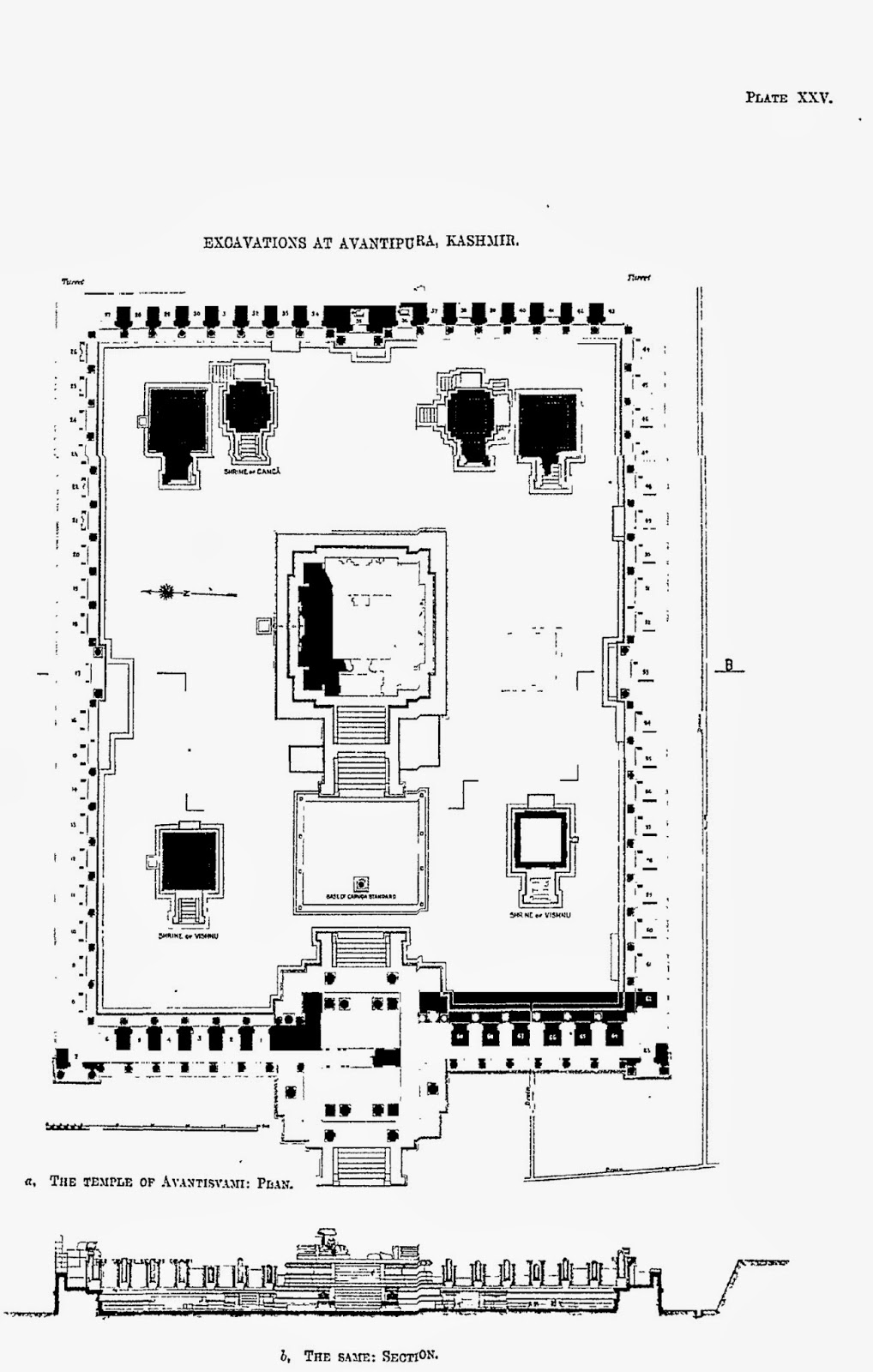

Then in 1913, Daya Ram Sahni did the second and most extensive round of excavations at the site. His findings were first published in ‘Annual report of the archaeological survey of India 1913-14’ under title ‘Excavations at Avantipur’.

It was this dig that uncovered the structures that we see it today at the site. The excavation also revealed artefacts that shed light on the way Kashmiris lived their life during various eras as coins of various kings and earthenware were uncovered. Among other things he found earthen heating bowls, the kind used by boatmen and poor in Kashmir. He found jars with still some corn in them, the same kind that were used in Kashmir till recent times. He found evidence that during various eras, a part of the structure may have continued to be used as a religious site by the Brahmins.

The ruinous state of the ancient temple (as in case of almost all ancient temples in Kashmir) was and is attributed to Sikandar Butshikan. But, supporting an earlier claim by Cunningham, Sahni found that “The courtyard of the temple had filled up with silt for more than two-thirds of the height of the colonnade already before the time of Sikandar [Butshikan].” During violent eras only the structure above ground had suffered. In this way one of Kashmir’s the most finely decorated ancient structure was discovered. It’s fortunate well preserved state a result of nature’s small mercy in the form of silting from either a catastrophic event or slow changing of Vitasta’s course and it’s flood area saving it from the hands of both man and nature during much of 13th and 14 century.

|

| Photo2: Ground Plan of Awantiswamin temple by Sahni |

Awantiswamin temple was built by Avantivarman in around 855 CE. Kalhana’s Rajatarangini tells us it was just before his accession to throne and also mentions that this was this fortress like temple in which royal officers of King Jayasimha (1128-1154 A.D.) successfully survived a siege by Damaras (feudal barons of ancient Kashmir), an event that must have occurred during Kalhana’s time. Before the excavation, some of the observers had assumed that the temple was dedicated to Shiva (Baron Hugel without much evidence actually thought it was a Buddist temple) . But once the base of the temple was excavated, Awantiswamin temple was found to be devoted to Vishnu. Avantivarman did built a Shiva temple which is nearby and is now known as Avantishovra Temple.

|

| Photo 4 |

|

| Photo 5 |

|

| Photo 6 |

|

| Photo 7 |

|

| Photo 8: Built in Grey Limestone prone to vagaries of nature |

|

Photo 9: Ganga in niche on left with lotus in right hand, quadrangle porch, outer chamber, northern wall.

Identified because in left hand she has a vessel and is riding a crocodile |

|

| Photo 10 |

|

| Photo 11 |

|

Photo 12: Yamuna in niche on right with lotus in left hand, quadrangle porch, outer chamber, southern wall.

Her ride, the tortoise was missing even in 1913 [more about Ganga Yamuna iconography in Kashmir] |

|

| Photo 13: Medallions in lower part represent Garuda |

|

| Photo 14 |

|

| Photo 15 |

|

| Photo 16 |

|

| Photo 17 |

|

| Photo 18 |

|

| Photo 19 |

|

| Photo 20 |

|

| Photo 21: Left wall to the stairs. |

|

| Photo 22: Six armed Vishnu with his consorts |

According to Sahni, “To his right and left are Satyavama and Sri. The emblems in the right hands of Vishnu are a mace (dada), a garland and an ear of corn (manjari). The uppermost left hand has a bow (pin aka, and the lower most a lotus bud. the middle hand rests on the left great of the goddess on that side. In front of the seat on which Vishnu sits are three birds, apparently parrots. The tilaka on the foreground of the central figure is a circular dot. Thos on the foreheads of the goddesses are dots enclosed in crescents. The panel is enclosed in square-pilasters of quasi-Greek type, surmounted with a multi foil arch with a goose in each spandril.”

|

| Photo 23 |

|

| Photo 24: Right block of the staircase |

|

| Photo 25:

Sahni presumed this one too to be of Vishnu. He writes, “The subject depicted on the front of the other flank is identical, except that the figure of Vishnu is four-armed and his forehead-mark is similar to that of the goddesses.”

But later scholars (Sunil Chandra Ray in Early History and Culture of Kashmir) mention it as

“Kamadeva with his wives Rati and Priti”

[update April, 2016: The identification of Kamadeva was done by J. Vogel in 1933 while reviewing Kak’s book for annual Bibliography of Indian archaeology 1933, Vol. 8] |

|

| Photo 26: Left block of the staircase |

|

Photo 27: King with his queens and attendants

Inner side of Left block near stair case

Sahni, had suggested that it might be the image of a Brahma. The scholars now agree the the image represents the chief patron of the temple, the King. “Whether the fiure stands for King Utpalapida, Sukhavarman who became the de facto ruler or Avantivarman himself is not know”[Debala Mitra, Pandrethan, Avantipur & Martand, 1977]

|

|

Photo 28: The Geese Motiff

also found on Harwan tiles |

|

| Photo 29: A Harwan tile |

|

Photo 30: Prince with his queens and attendants

Inner side right block |

|

| Photo 31 |

The particular block is interesting as Sahni in 1913 had identified it as Krishna and the Gopis. He writes, “The central figure presumably represents the youthful Krishna standing facing with a flower bud in each hand. To his right and left are archangels bringing presents of sweets and garlands in the upper corners. To the proper right of Krishna we notice a pair of figures, the lower one being a female (cowherdess), who is feeding a cow from a bowl. The other figures on this side and the four figures on the other side may be cowherd boys (gopa).”

The scholars [Debala Mitra, Pandrethan, Avantipur & Martand, 1977] now consider this to be image of a Prince, possibly Avantivarman.

|

| Photo 32 |

|

| Photo 33: Inner Courtyard |

|

Photo 34: The central structure

Back in 1913, Sahni noticed that the blocks were used by people as construction material in Srinagar.

The central statue was never found only parts of pedestals |

|

| Photo 35: Left block was dedicated to Ganga. These are of a slightly later date than the main structure. |

|

| Photo 36 |

|

| Photo 37 |

|

| Photo 38 |

|

| Photo 39 |

|

| Photo 40 |

|

| Photo 41 |

|

| Photo 42 |

-0-

Under ASI, it is one of the best maintained of ancient monuments in Kashmir. The entrance only costs rupees five. I visited the place in the afternoon of 22 February 2014 in midst of wintry showers. There were no tourists. I found my self alone in the ruins. Well, almost alone. The government tourist guide, a guy with a crazy eye, proved to be surprisingly good. He knew the basics and the important elementary facts about the site perfectly. He took no extra money for the service and in fact refused extra money. At the end of his guided tour, he was in for a pleasant shock when he realised that I was no normal tourist but a fellow Kashmiri.

If the place was somehow again buried today, in a couple of hundred years when they dig it up again, they would find bottles of cold drink and assume the climate of Kashmir had started changing. They would look at the marks of fresh violence on the stones and assume man was heading no where.

-0-

To be updated with download link for Sahni’s papers.

Read: ‘Excavations at Avantipura’ by D. R. Sahni in ‘Annual report of the archaeological survey of India 1913-14’.