Guest post by Man Mohan Munshi Ji. He writes:

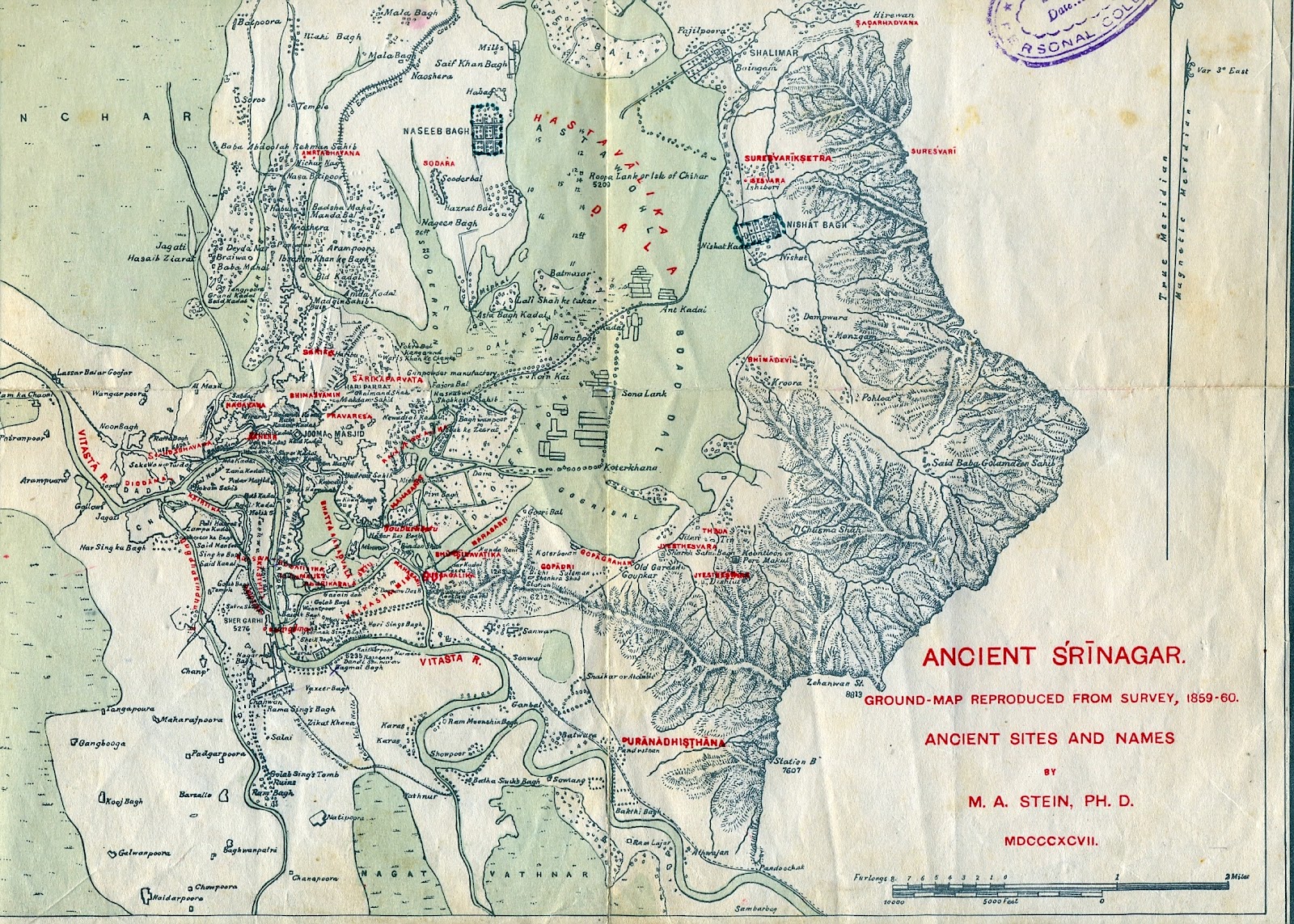

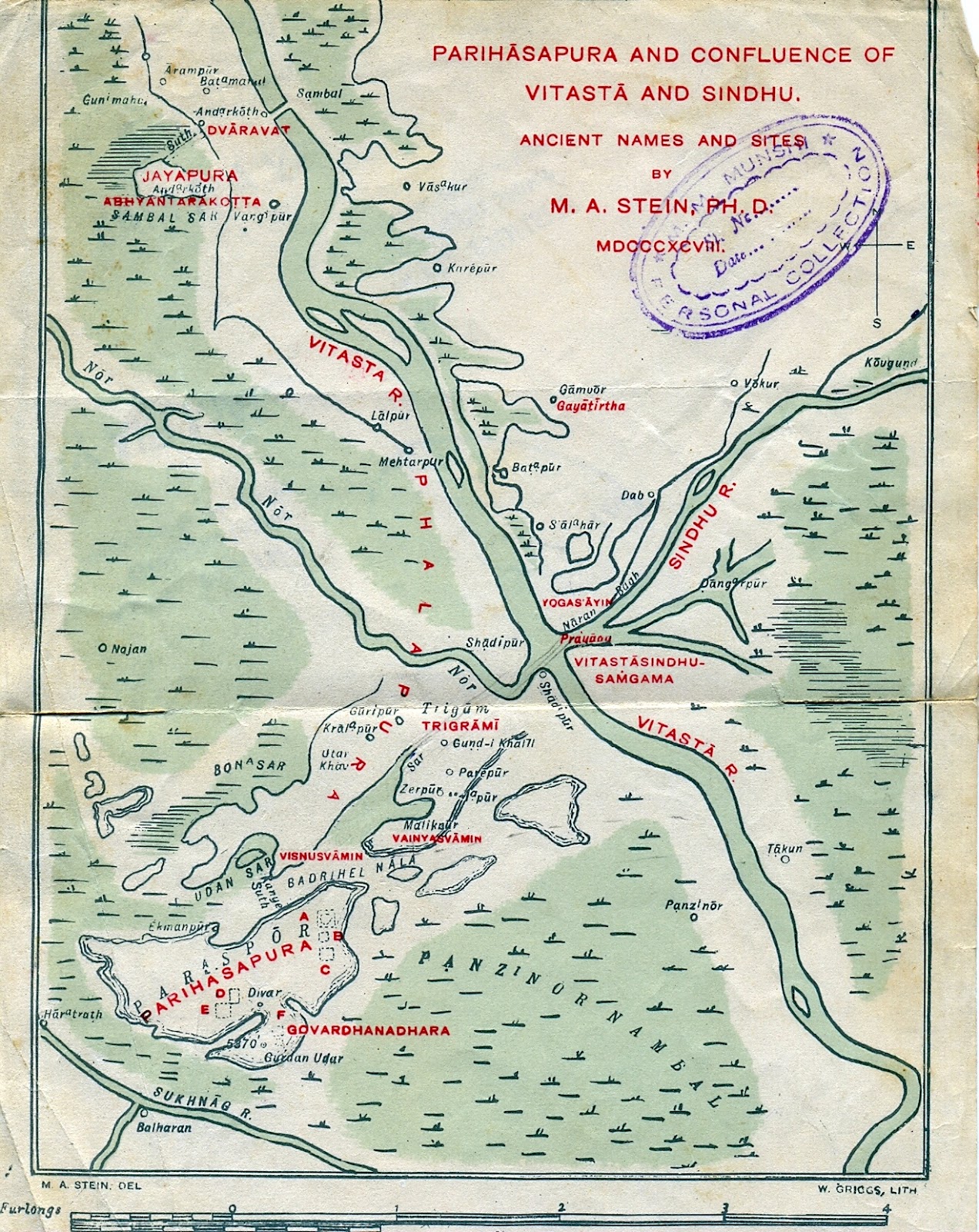

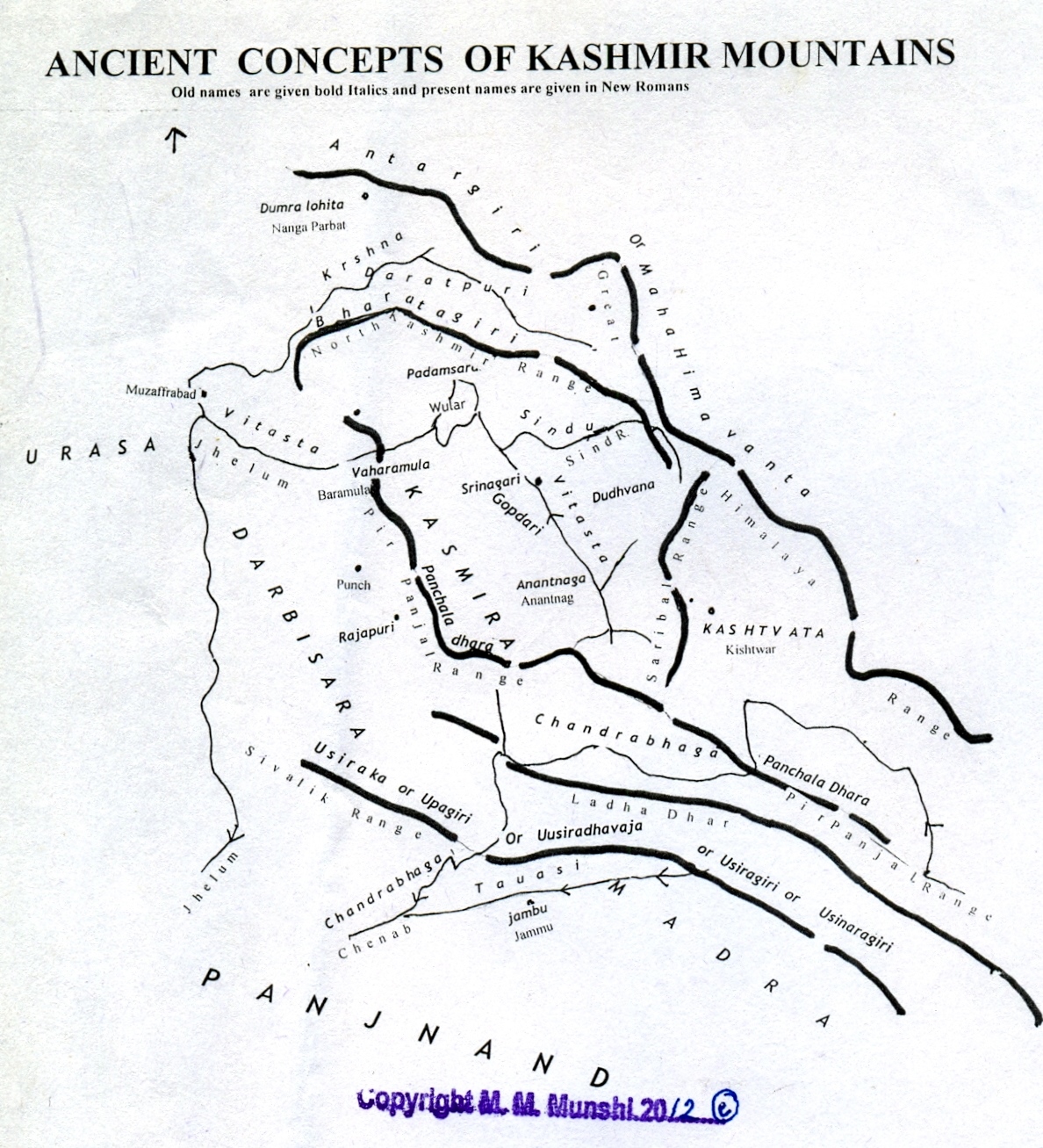

The following six images pertain to the temple of Govardanahara, built and dedicated by Laltaditya Mukhpida of Karkota Dynasty in 8th century AD, one of the greatest Monarchs who ever ruled Kashmir. The great Monarch founded his capital at Parihaspura and built numerous temples of Vishnu, Shiva and Bhudha. He built Viharas, Agarharas and palaces at and around

Parihaspura. According to Kalhana a silver image of Vishnu was installed in the Govardanahara temple. But the capital did not survive for long as the royal residence was removed by his son Vajradatya. The Vitastasindhusamgama which during Laldatiya existed between Parihaspura and Trigami (

Trigom) karewas was shifted to its present location opposite Naranbagh by Soyya, the able engineer of King Avantivarman in 9th century who shifted the capital to Avantipura. Later the temples were vandalised during the Muslim rule during 14th-15th century.

|

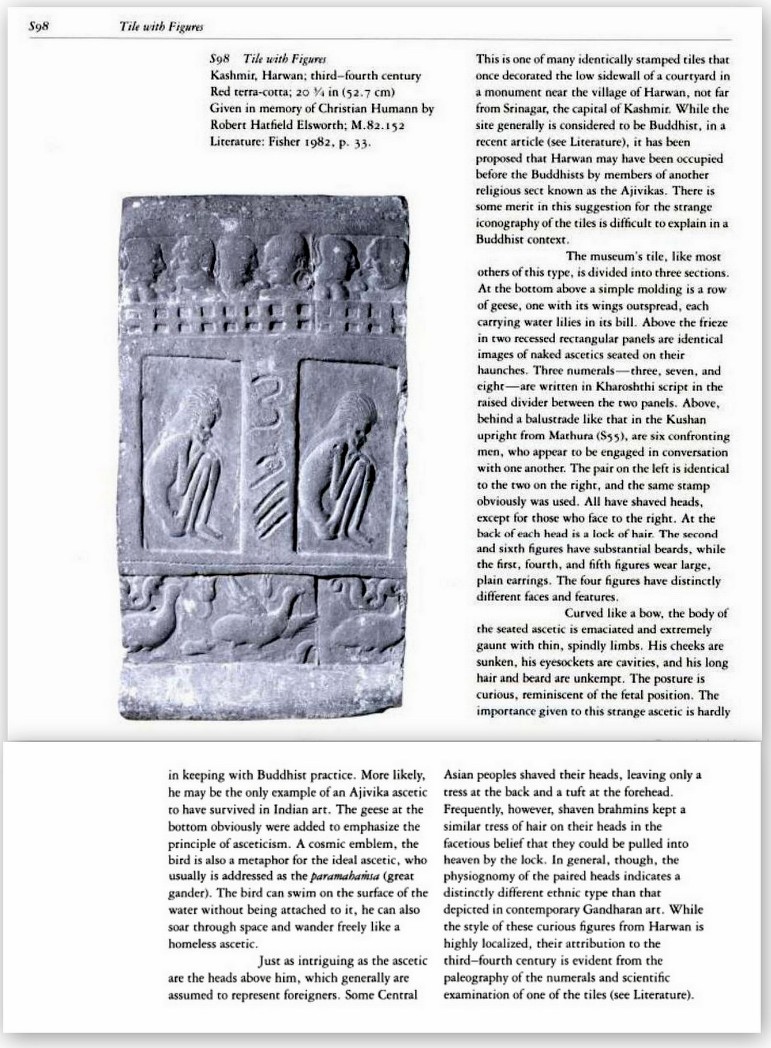

| Distant view of Govardanadhara temple

|

|

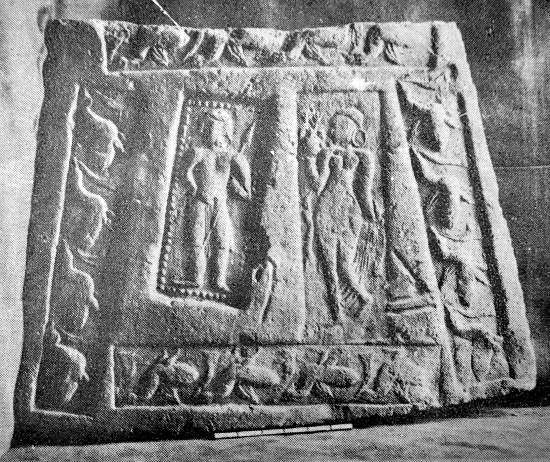

| Closer view of the ruins only staircases and plinth is left

|

|

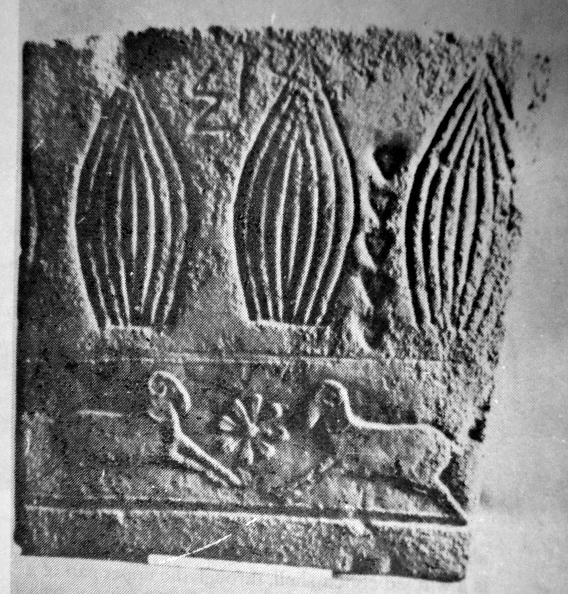

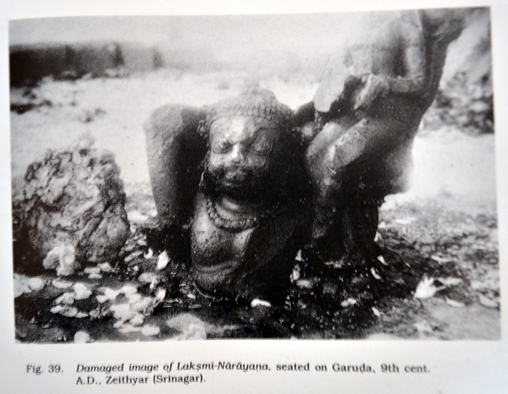

| Only surviving statues

|

|

| ASI Notice Board |

-0-

To these images I am adding following notes:

Note on the ancient site by Pandit Anand Koul from his book ‘Archaeological Remains In Kashmir’ (1935) . [You can read the complete book here]:

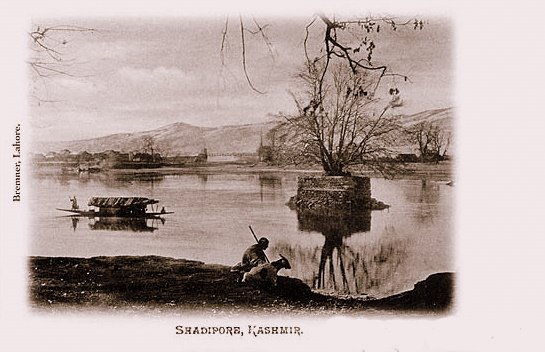

Ruins at Paraspur

The site of ancient Paraspur (Parihasapura) lies nearly 2 1/2 miles south-west from Shadipur. On leaving the boat one crosses some corn field and, after ascending a gradual slope and passing through Trigam, reaches the plateau on which the ancient mounds rise. This city, says Kalhana, was founded by Lalitaditya Muktapida (A.D. 701-37) one of the greatest sovereigns of Kashmir, and a brief account is given of the five large buildings he erected here viz.,(1) the temple of Mukta-keshva with a golden image of Vishnu, (2) the temple of Parihasa-keshava with a silver image of Vishnu.(3) the temple of Mahavaraha with its image of Vishnu clad in golden armour, (4) the temple of Govardhanadhara with a silver image and (5) the so-called Rajavihara with a large quadrangle.

Here was a colossal statue of Buddha in copper. The confluences of the Sindhu and Vitasta was at this place inn ancient times. It was a very renowned place in by-gone days. There are many ruins of ancient temples still found in and near it, e.g.(1) temple ruins at Paraspur, (2) well preserved foundation of the temple of Vainya-swamin on the Paraspur Udar, near Ekmanpur, and (3) ruins at Malikpur. Of the temples to the west of Divar village there remains only a confused mass of huge blocks. The quadrangle too is utterly ruined and traceable only by wall foundations and broken pillars, etc. The large dimensions of these temples are indicated by the fact that the peristyle of the one further to the west formed a square of about2 75 feet. and that of the other an oblong of 230 feet by 170 feet. There are other ruined temples at this place, but they are all in a state of destruction. On the top of the mound lies a block remarkable for its size, being 8 1/2 feet square and 4 1/2 feet in height which, to judge from the large circular hole cut in its centre, must evidently have formed the base of a high column, or of a colossal image. The character of the ruins at Divar agrees exactly with that of the shrines mentioned in Kalhana’s account.The shrine Vainya-swamin can be recognized with certainty in the ruined temple at Malikpur, one mile from the northern group of the Divar ruins. Sir Aurel Stein writes in the Rajatarangini about this place: –

“The vicissitudes, through which Parihaspura has passed after the reign of Lalitaditya, explain sufficiently the condition of utter decay exhibited by the Divar ruins. The royal residence, which Lalitaditya had placed at Parihasapura, was removed from there already by his son Vajraditya. The great change of the Vitasta, removed the junction of this river with the Sindhu from Parihasapura to the present Shadipur,nearly three miles away. This must have seriously impaired the importance of Parihasapura. Scarcely a century and a half after Lalitadiya’s death,King Shankaravarman (A.D. 883-901) used materials from Parihasapura for the construction of his new town and temples at Pattan. Some of the shrines, however, must have survived to a later period, as we find the Purohitas of Parihasapura referred to as an apparently influential body in the reign of Samgramaraja (A.D. 1003-28). Under King Harsha the colossal Buddha image of Parihasapura is mentioned among the few sacred statues which escaped being seized and melted down by that king. The silver image of Vishnu Parihasakeshava was subsequently carried away and broken up by King Harsha. The final destruction of the temple of Parihasapora is attributed to Sikandar But-Shikan (A.D. 1394-1416).Even up to the year 1727 A.D. the Paraspur plateau showed architectural fragments of great size, which have since been carried away as building materials.It is interesting to find that these ruins were yet at a comparatively so recent time generally attributed to Lalitaditya’s building”

-0-

Aurel Stein made a spot visit to Paraspora in Sept. 1892. There he traced the actual ruins of the building describedin the Rajatarangini. These remains were situated near the village Sambal on a small plateau (Udar) between themarshes of Panznor and village Haratrath. Stein identidied five great buildings which Lalitaditya had erected at Parihaspura. These were identified as Parihasakeswa, Mukatakeswa, Mahavaraha, Govardhanadhara and Rajavihara.The first four were temples dedicated to worship of Vishnu and the last named was a Buddhist convent. However whenrevisiting the site in May 1896, Stein found many of the stones missing that existed in 1892. On inquiry heleared that these stones were taken away by the contractors engaged in building the new Tonga road to Srinagar.To prevent such callous damage that was being caused to these relics of past, Stein made a representation to theResident Sir Adelbert Talbot for urgent need of protecting the remains. The Resident supposted his petition andeffective steps were ordered by the Maharaja to prevent repetion of similar vandalism

~ via siraurelstein.org

-0-

Note on the site from ‘Ancient Monuments of Kashmir’ (1933) by Ram Chandra Kak.[Read the complete book here at KOA]:

|

| Plate LV

|

The karewas of Paraspor and Divar are situated at a distance of fourteen miles from Srinagar on the Baramula road. They were chosen by King Lalitaditya (c. A.D. 750) for the erection of a new capital city, and it is certain that, given a sufficient supply of drinking water, the high and dry Plateaus of Parihasapura have every advantage over the low, swampy Srinagar as a building site. Lalitaditya and his ministers seem to have vied with each other in embellishing the new city with magnificent edifices which were intended to be worthy alike of the king’s glory and the ministers’ affluence. The Plateau is studded with heaps of ruins of which a few have been excavated. Among these the most important are three Buddhist structures, a stupaj a monastery, and a chaitya. Their common features are the enormous size of the blocks of limestone used in their construction, the smoothness of their dressing, and the fineness of their joints. The immense pile at the north-eastern corner of the Plateau is the stupa (Plate LV) of Chankuna, the Turkoman (?) minister of Lalitaditya. Its superstructure has entirely disappeared, leaving behind a huge mass of scorched boulders which completely cover the top of the base. There is a large massive block in the middle of this debris, which has a circular hole in the middle, 5′ deep. It is probable that this stone belonged to the hti (finial) of the stupa, and that the hole is the mortice in which was embedded the lower end of the staff of the stone umbrellas which crowned the drum.

The base is 128′ 2″ square in plan, with offsets and a flight of steps on each side. Its mouldings are of the usual type, a round torus in the middle and a filleted torus as the cornice. The steps were flanked by plain rails and side walls which had pilasters in front decorated with carved figures of seated and standing atlantes. Some of these are in position, while others, which were lying about loose, have been transported to the Srinagar Museum. They are not grotesque creatures like those so commonly seen in Gandhara, but have the appearance of ordinary respectable gentlemen, whose placid features seem to indicate that the superincumbent weight sits lightly upon them. The top surface of each of the two plinths is broad and affords adequate space for circumambulation. Among the loose architectural stones lying scattered about the site are a few curious blocks in the south-eastern and south-western corners. They are round torus stones adorned with four slanting bands or fillets running round the body. As this type of torus moulding is not used in either of the bases, it is probable that it belonged to the string-course on the drum of the stupa. There are fragments of trefoiled arches also, which contained images of the Buddha and Bodhisattvas.

The large square structure to the south of the stupa is the rajavihara, or royal monastery. A flight of steps in the east wall gives access to one of its cells which served as a verandah. The monastery is a quadrangle of twenty-six cells enclosing a square courtyard which was originally paved with stone flags, some of which are extant. In front of the cells was a broad verandah, which was probably covered, the roof being supported by a colonnade which ran along the edge of the plinth. A flight of steps corresponding to the one mentioned above leads down to the courtyard. Exactly opposite to this, in the middle of the west wall, are three cells preceded by a vestibule, which is built on a plinth projected into the courtyard. It is probable that these were the apartments occupied by the abbot of the monastery. Near a corner of it is a large stone trough, which may have served as a water reservoir for bathing purposes. A couple of stone drains passing underneath cells Nos. 18 and 21 (if we begin counting from the cell to the south of the entrance chamber) carry off the rain and other surplus water from the courtyard. Externally the plinth is about 10′ high. In cell No. 25 (that is the one to the north of the entrance chamber) was found a small earthen jug which contained forty-four silver coins in excellent preservation. They belonged to the time of kings Vinayaditya, Vigraha, and Durlabha. They are now exhibited in the Numismatic Section of the Srinagar Museum. The monastery was repaired at a subsequent period. The repairs are plainly distinguishable in the exterior of the wall on the eastern and western sides.

The building next to it on the south side is the chaitya built by Lalitaditya. It stands on a double base of the usual type. A flight of steps on the east side leads to the entrance, which must originally have been covered by a large trefoil-arch, fragments of which are Iying about the site. This building possesses some of the most massive blocks of stone that have ever been used in Kashmiri temples, and which compare favourably with those used in ancient Egyptian buildings. The floor of the sanctum is a single block 14′ by 12′ 6″ by 5′ 2″.

The sanctum is 27′ square surrounded by a circumambulatory passage. It is probable that its ceiling was supported on four columns, the bases only of which survive at the four corners. The roof, which was probably supported on the massive stone walls of the pradakshina, may have been of the pyramidal type.

The courtyard is enclosed by a rubble-stone wall which has nothing remarkable about it. In front of the temple steps is the base of a column which probably supported the dhvaja, or banner, bearing the special emblem of the deity enshrined in the sanctuary.

The flank walls of the stair were adorned with atlantes similar to those of the stupa.

Near the chaitya is the foundation of a small building of the diaper-rubble style.

While this Plateau was reserved for the erection of Buddhist buildings only, the other two were exclusively appropriated by Hindus. Perhaps the arrangement was intentional, to avoid possible friction between the two powerful religious bodies. On the karewa locally known as Gordan there are ruins of a Hindu temple which are probably all that remain of Lalitaditya’s temple of Govardhanadhara. Crossing the ravine in which nestles the little village of Diwar- Yakmanpura, and ascending the Plateau opposite, are seen the immense ruins of two extraordinarily large temples – one of them has a peristyle larger than that of Martand – which may represent Lalitaditya’s favourite shrines of Parihasakesava and Muktakesava.

-0-

The temple is an ancient one but not much is known about its antiquity. Some time back it was reported in the print media that it was recently uncovered. I visited the place last month and found that a parapet and fence was built around it but the level of water has remained the same and water was oozing out from an underground spring. I took a plunge inside the water logged temple and felt with my hands about one foot tall Shivling inside the temple.

The temple is an ancient one but not much is known about its antiquity. Some time back it was reported in the print media that it was recently uncovered. I visited the place last month and found that a parapet and fence was built around it but the level of water has remained the same and water was oozing out from an underground spring. I took a plunge inside the water logged temple and felt with my hands about one foot tall Shivling inside the temple.