From – ‘R.D.Burman The Man, The Music'(2011) by Anirudha Bhattarcharjee and Balaji Vittal.

-0-

The two Kashmir words were finally passed off in the song to mean I love you and I need you.

in bits and pieces

From – ‘R.D.Burman The Man, The Music'(2011) by Anirudha Bhattarcharjee and Balaji Vittal.

-0-

The two Kashmir words were finally passed off in the song to mean I love you and I need you.

-0-

Last week, thanks to my super vanity – a habit of self-googling, I realize ‘Fish‘ got posted to some newspaper called kashmirmonitor [kashmirmonitor.org/krkashmirmonitor/08232011-ND-strange-tales-from-tulamula-10326.aspx]. Although my name as the author is there next to the miss-titled story, ‘Strange Tales from Tulamula’, no one wrote to me asking ‘Hey, nice stuff, can we use it?’, No, it just got posted, filled up a space. Served what purpose? No clue. What monkey business! And what harbingers of new social change.

-0-

Two nights ago, I run into more monkey business. I was going through comments section of various articles on Kashmir Current Affairs. My sorry excuse for this despicable exercise is that inspite of all my genuine efforts, I still regularly fail at entirely burying myself in Past, and sometime I too get tempted to get in touch with Present whose commentary offers us the LOLs of future. So I was digging comments. And I ended up the gallery of vintage photographs collected from “various sources” set up by an online newspaper called ‘kashmirdispatch’ [kashmirdispatch.com/gallery.html]. Yes, among other stuff ( some new even for me, sourced from who knows where) I saw Vintage photographs of Kashmir that I have been posting for more than two years now, with notes on dates, places, photographers and sources. That’s more than 60 post with more than And I saw stuff that Man Mohan Munshi Ji posted on this blog from his personal collection, like The paperwallas just post it on their website as part of a gallery without any adjoining description. The exercise serves what purpose?

When I started posting, I could have easily put a big ‘Search Kashmir’ logo on all of them. But that would not have served the purpose of their existence. The fact that these photographs were shot by someone long ago, and that they were used in detailed narratives about an exotic foreign land written mostly by men (and in some cases by women) seemingly burning with a strange zeal for information, and the fact that these photographers were mostly always duly acknowledged, that these photographs were preserved for years, and only now scanned for free by billion dollar companies, that part of the story of these photographs tells us just as much about the politics of information as the manner in which we the ‘subjects’ now use or misuse these information. And right now I think we, in this part of the impoverished world, still don’t get it.

-0-

On one hand I have newspaperwallas who just Monitor and Dispatch and on other hand I have people who are kind enough to drop in a line before even posting stuff to their Facebook Walls. For people who use this blog, please feel to use use whatever you want but…try to give credit where it is due. If this post leaves you confused enjoy this video by Nina Paley.

When the smoke lessened, the policemen saw that their quarry was a Kashmiri coolie. He was lugging a heavy sack and running with admirable ease despite the weight on his back. The policemen’s throats ran dry with blowing their whistles, but the Kashmiri coolie’s pace didn’t slacken.

By now, the policemen were panting. Tired and fed up with the chase, one of them took out a gun anf fired. The bullet hit the man in his back. The sack slipped and rolled down. The man turned, and looked at the still-running policemen with frightened eyes. He also saw the blood seeping down his calf. But with a quick jerk, he bent bent, picked up the sack and began to limp away hurriedly. The policemen thought,”Let him go to hell.”

The Kashmiri coolie was limping badly when he staggered and fell heavily – the sack fell on top of him.

The policemen swooped down on him and took him away to the police station. The man kept pleading all the way,”Gentlemen, why are you arresting me? I am a poor man…I was only taking a sack of rice…to eat at home…why have you shot me…” But no one paid him any heed.

The Kashmiri coolie went on with his explanations at the police station, pleading and crying,”Sir, there were others in the bazaar…they were carrying away many big things…I have only taken one sack of rice…I am a poor man…I can only afford to eat plain rice.”

Till, finally, he gre tired and desperate. he took off his skull-cap, wiped the sweat streaming from his forehead, cast one last, lingering look at the sack of tempting rice, then stretched his palm before the Thanedar abd said,”All right, sir, you keep the sack with you…but pay me my labour charges – four annas.”

Extract from cameo titled ‘Payment’ from ‘Black Borders: A collection of 32 cameos’, Rakhshanda Jalil’s translation of Saadat Hasan Manto’s Siyah Hashiye (1947).

-0-

Image: Kralkhod, Srinagar, 2008

-0-

Previously: Pundit Manto’s First Letter to Pundit Nehru

‘You should not have left Kashmir’

The shawl seller from Kashmir concluded while trying to show his ware. Something about the statement ticked off Veena.

‘You should be glad my brother’s are not at home. They would have answered it better. No, I don’t want to buy anything. Please, leave!’

-0-

My first Id was at the house of Tabassum, friend and colleague of my bua Veena Didi. I remember eating sevaiya at the house of her friend somewhere in downtown Srinagar . I remember how excited about visiting the house of the famous friend of my dear bua. They would run experiments on rabbit blood. I would ask her if I were to visit her office, would I see rabbits, white rabbits. She promised, I went, but I never saw any rabbits. Her office smelt of hospitals. It was a hospital. That year, besides her impeding marriage, she was excited about the new imported machine in her office. This machine could churn blood at an unimaginable RPM, round and round, separating blood into fine individual components for study. Among her sibling she was the only one to have gone outside the state to study. It was a time she was to always remember fondly. I remember how excited I was about eating real sevaiya. I remember the shops in the area, the pistols, that looked too real and the police holsters, that were certainly real, handing from the roof of those shops. I was obsessed with Bandook that year. Guns were all I could think of that year. Diwali was just around the corner. I wanted a gun that year. The visit turned out to be a formal affair. We were sitting, on floor, in the drawing room of a house that looked newer than the house in which I was born. Tabassum served the dishes. Sevaiya were different and certainly better. And then we left.

-0-

She was the first one to leave.Veena didi finally got married in Jammu in middle of a cerfew over an issue that would roll-ball into what would be remembered as ‘mandal comission’. A year after her marriage, some people from Kashmir paid her new home a visit.

‘Where is Veena?’ That is all the woman at the door wanted to know.

Veena’s mother-in-law was in a fix on hearing this question. At first she was suspicious of the Muslim brother-sister duo that had come inquiring about the whereabouts of her daughter-in-law. Al though her family had a house at Chanapora, she had spent most of her own married life in Amritsar. How do they know? How did they find out? Terrorist? These thoughts filled her up instinctively. But on hearing a lengthy explanation on the nature and depth of relationship, she was convinced enough to tell them,’Veena is at the place of her parents. Perhaps you should come some other time. Sorry!’

‘Okay, take us there. I won’t leave without meeting her.’

Shocked as she was at this unabashed display of emotion, under duress and with a word of advice, ‘Take Care’, she deployed Veena’s husband to accompany the brother-sister duo to the place of Veena’s in-laws.

It was a colony which was in winter filled with ‘Durber move’ Kashmiris. It was the place were I celebrated a couple of more Ids growing up with boys from Kashmir who would bowl like Imran Khan and Wasim Akram. Boys who taught me reverse swing even before the rest of the world knew it.

‘How could you not invite me to your marriage? You thought I wouldn’t come?’

‘How could I?’

With that the two friends, Tabassum and Veena hugged each other. Veena welcomed her into the two-roomed house of her parents.

-0-

I have no recollection of the second event. It’s a story my Bua likes to recall sometime. She went on to teach herself programming just around the time when I first started to pick it up in school. In her exercises to keep herself busy, a thought that filled minds of a few pandits in Jammu, on weekdays she teaches computer science to village kids, who in Summer sometimes bring her offering of Mangoes, and on weekends she spends a lot of her time in the ashram of a Kashmiri Saint freshly relocated to Jammu. I think she misses her imported Beckman machine and the rabbits. She tells me she again heard from Tabassum a few years back. Tabassum is married and in U.K. May on somedays, she too misses that blood churning machine and those white rabbits.

-0-

|

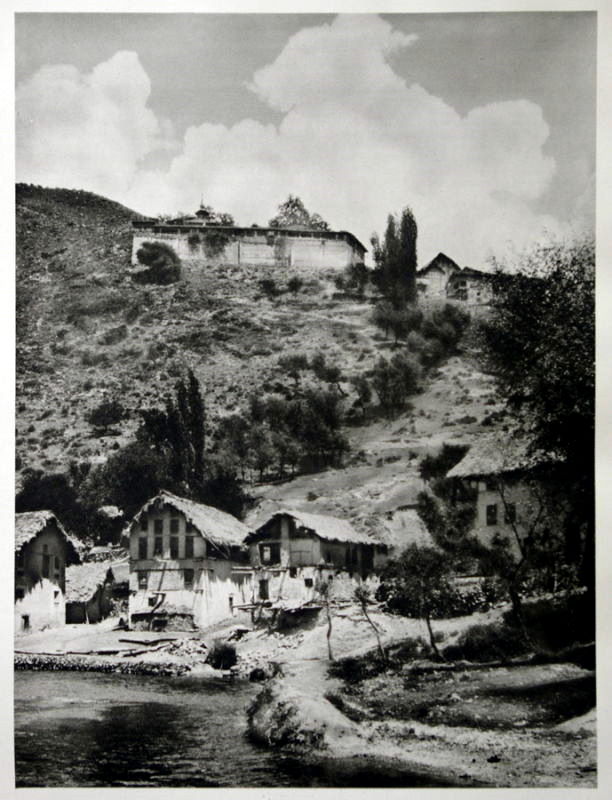

| A Rural House. 1927 |

|

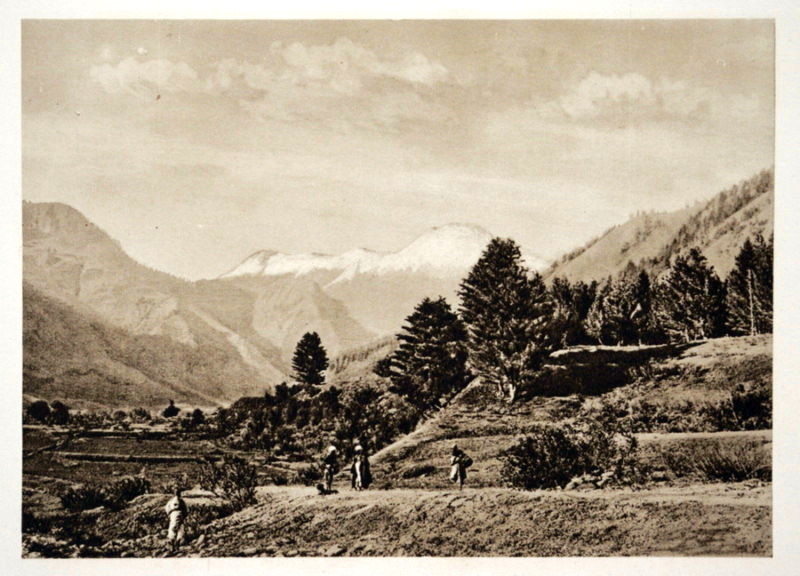

| Some where on way to Gulmarg. 2008. [some more houses] |

|

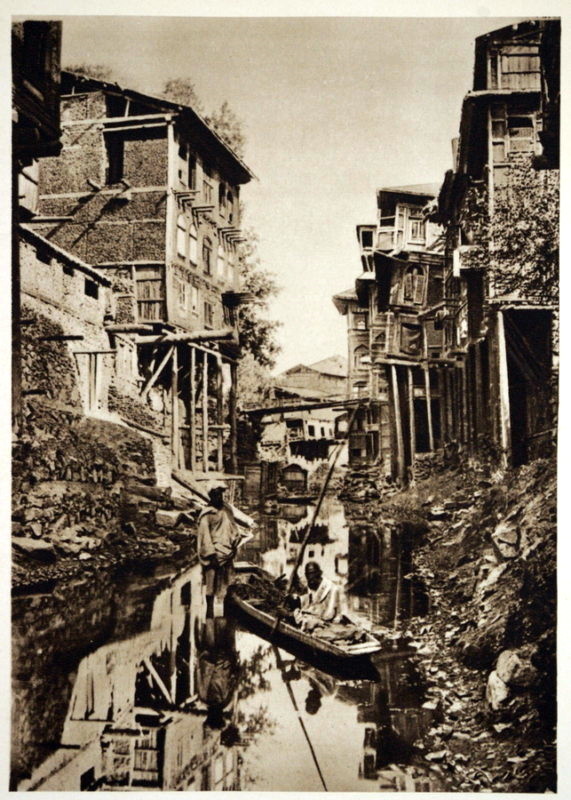

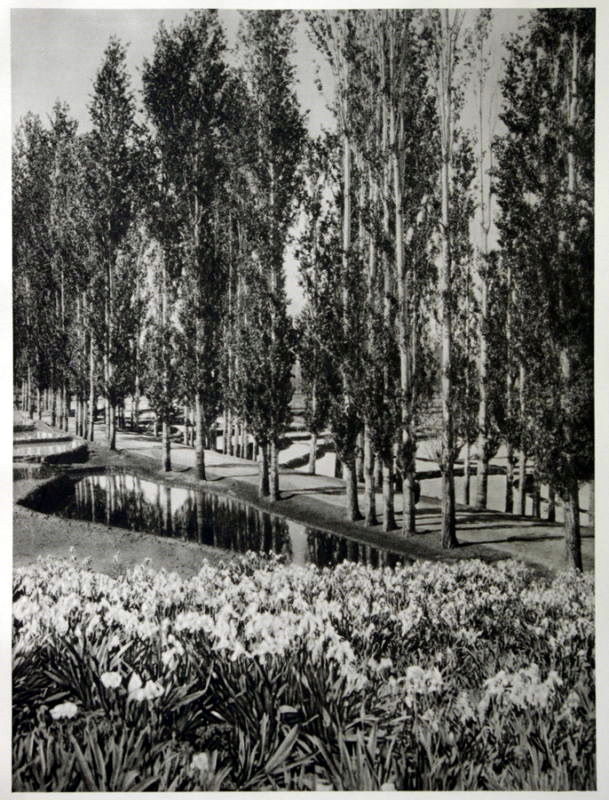

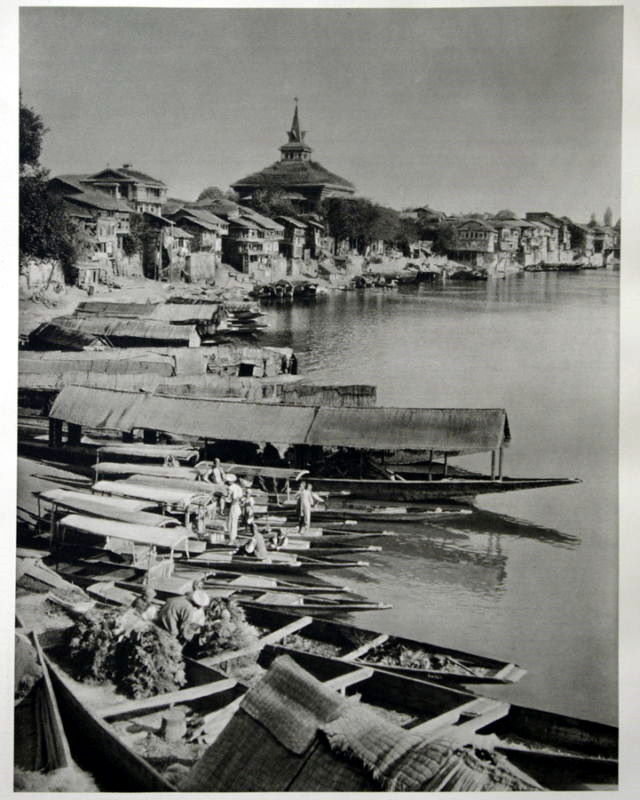

| Mar Canal by Martin Hürlimann (?) |

|

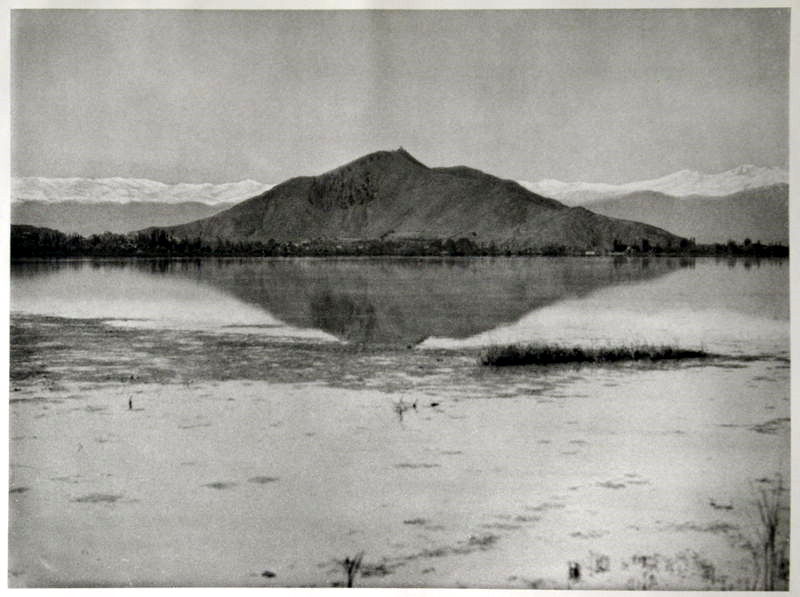

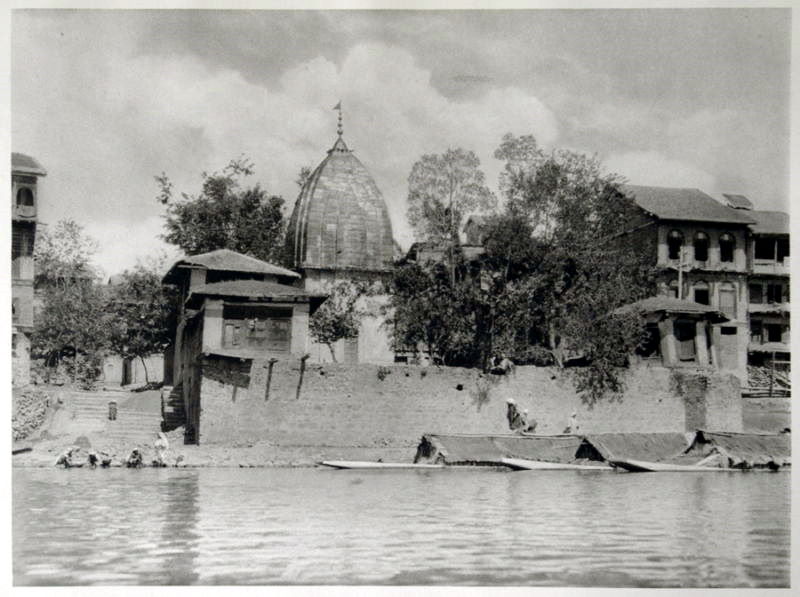

| Dal Lake |

|

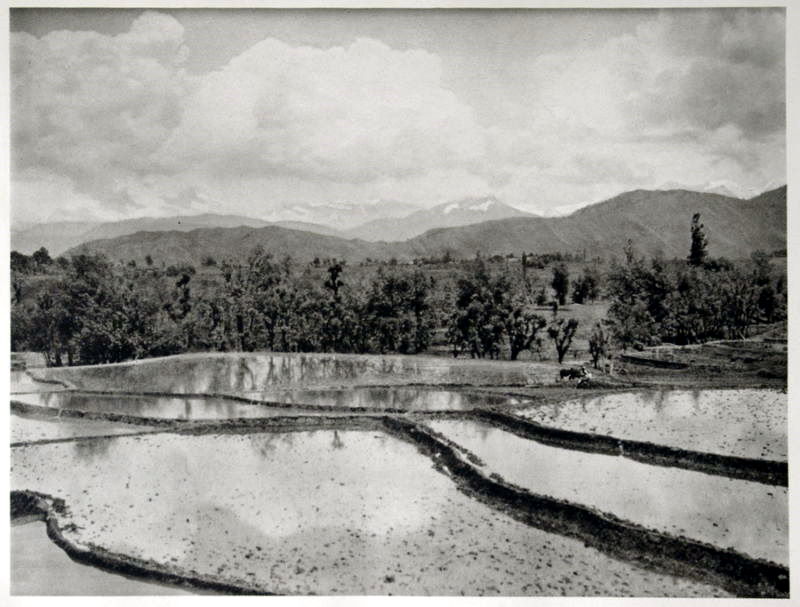

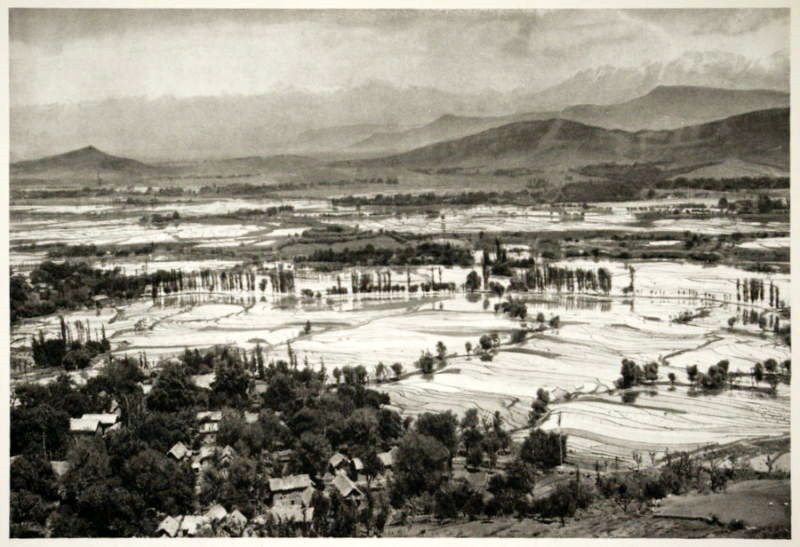

| Paddy Fields |

|

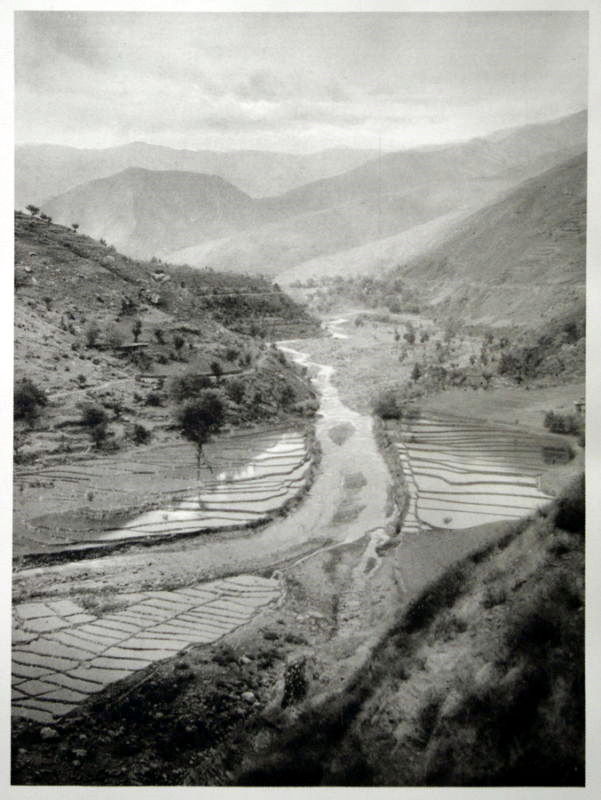

| Paddy fields near Qazigund, 2008 |

|

| view of Qazigund |

|

| View 2008. Previously: View of valley and Hügel’s Atmospheric phenomena |

|

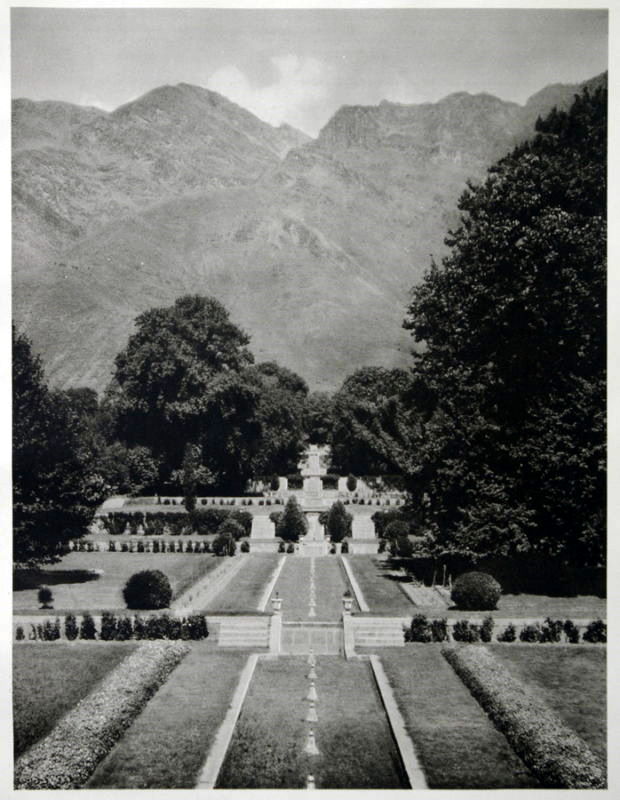

| Nishat |

|

| History of Nishat |

|

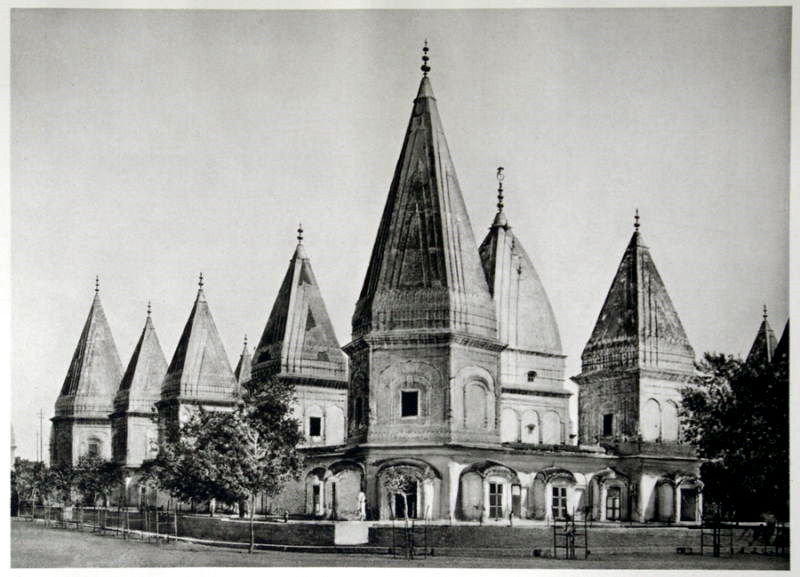

| Raghunath Temple Jammu |

-0-

Continuing with the tradition [pick from year 2010], this year’s loot include:

In This Metropolis

by Hari Krishan Kaul.

Translated by Ranjana Kaul.

2011. Rs. 75.

It’s a collection of short stories by a Kashmiri writer (b 1934) known for his kafkaesque style. This is the translation of his year 2000 Sahitya Akademi Award winning collection ‘Yath Raazdaane’. This was the first time a Kashmiri won the award for short stories. The book starts with writer’s re-working of a Lal Ded saying rendered as:

My wooden bow has but arrows

made of grass

This metropolis (of my mind),

has been entrusted to an unskilled carpenter’

Kashmir Hindu Sanskars: Rituals, Rites and Customs

by S.N. Pandit

2006.Rs 475

Published at Kashmiri Pandit run Gemini Computers, Jammu

Sponsored by Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi

Based on year 1982 research paper by the author “Kashire Battan Hindi Rasim ti Rewaj”, this book is a definitive guide to living and dead rituals and festivals of Kashmiri Pandits. Peppered with arcane Kashmiri folk lyrics associated with various rituals and festivals, this book is a treasure. My mother, much to her delight, actually managed to recall and sing some like ‘Diri diri honya, yati kyo yati kyah’, ‘Go away; go away dog, what is here? Who is here?’, Kashmiri lyrics reserved for times when inauspiciously dogs start howling.

A History of Kashmiri Literature

by Trilokinath Raina

First published by Sahitya Akademi in 2002.

2005. Rs.100

Trilokinath Raina’s erudite and precise contribution to Kashmiri Literature, its History. A must have!

Abdul Ahad Azad

by G.N. Gauhar

First published 1997. Rs.25

In the ‘acknowledgements’ to this biography of the great Kashmiri poet, we read ‘ The prevailing situation in Kashmir caused total damage to the approved typed manuscripts’ and about the poet we read that he was more of a Subash Chandra Bose fan than a Gandhi fan (unlike Mahjoor).

Zinda Kaul

by A.N. Raina

First published 1974.

1997. Rs.25.

Life sketch of a man who was perhaps the last of the ‘saint-poet’ of Kashmir.

Children’s Literature in Indian Languages

by Dr. (Miss) K.A. Jamuna

1982. Rs. 18

Al though Trilokinath Raina’s ‘A History of Kashmiri Literature’ does does upon children’s literature in Kashmiri language but given there isn’t much to right about, the section in actually only a paragraph. However, in this book we have a complete essay (not too detailed as compared to some other languages) by Ali Mohammad Lone on this oft ignored but important subject. And we get to read (in brief) about work of Naji Munawwar, perhaps the only dedicated Children’s writer from Kashmir.

Tales from The Tawi: a collection of Dogri Folk Tales

Suman K.Sharma

First published 2007. Rs. 60

Have no clue what to expect from this neat book for children. A good reason to get in Dogri folk tales!

Folk-Tales of Kashmir

by Rev. J Hinton Knowles

Second Edition

First published 1893

This famous book starts with a Shakespeare quote,’Every tongue brings in a several tale’. I have read most of the tales in this book online, now I have a hardbound copy. Hopefully someone will come with a Amar Chitra Katha version of these engrossing tales someday.

-0-

I first came across this image some years ago on columbia.edu site who in turn had picked it from ebay. Cited as ‘Kashmiri Brahmans’ and photographed by Francis Frith in around 1875, the image offered an enigma in the sense that its subjects seemed out of place, all the other photographs of Kashmiri Pandits taken during that era has pandit in his usual place, handling scrolls or roaming around temples. So who were these Brahmans and what were doing with those bundles of cloths?

I have finally managed to get through to the answers that this image demanded. The photograph is used and explained in ‘The Jummoo and Kashmir Territories: A Geographical Account’ (1875) by Frederic Drew. An excerpt:

First, standing out marked and separate from the rest, are the Pandits. These are the Hindu remainder of the nation, the great majority of which were converted to Islam. Sir George Campbell supposes that previously the mass of the population of Kashmir was Brahman. An examination of the subdivisional castes of both Pandits and Muhammadans, if it were made, might enable us to settle this question. Whatever may be the case as to that, we certainly see that at this day the only Kashmiri Hindus are Brahmans. These whatever their occupation-whether that be of a writer, or, may be, of a tailor or clothseller – always bear the title “Pandit” which, in other parts of India, is confined to those Brahmans who are learned in their theology.

The Kashmiri Pandits have that same fine cast of features which is observed in the cultivating class. The photograph given, after one of Mr. Frith’s, is a good representation of two cloth- sellers who are Pandits, or Brahmans. When allowance has been made far an unbecoming dress, and for the disfigurement caused by tho caste-mark on the forehead, I think it will be allowed that they are of a fine stock. Of older men, the features become more marked in form and stronger in expression, and the face is often thoroughly handsome. In complexion the Pandits are lighter than the peasantry; their colour is more that of the almond.

These Brahmans are less used to laborious work than the Muhammadan Kashmiris. Their chief occupation is writing : great numbers of them get their living by their pen, as Persian writers (for in the writing of that language they are nearly all adepts), chiefly in the Government service. Trade, also, they follow, as we see ; but they are not cultivators, nor do they adopt any other calling that requires much muscular exertion. From this it happens that they are not spread generally over the country; they cluster in towns. Sirinagar, especially, has a considerable number of them; they have been estimated at a tenth of the whole of its inhabitants.

Reader may make allowance of Drew’s ‘i believe because I believe’ assertion that Pandits were not cultivators.

Kashmiri Pandit women working the fields, 1890. [Update: They appear to be working in field, dying cloth and yarn here]

Reader may also make allowance of the fact the Drew didn’t get into the breakdown of Kashmiri Pandits into Karkun Bhattas (Working Class Pandits, into Govt. Jobs, into Persian, the one described by Drew) and Basha Bhattas (Language Class Pandits, into Religious affairs, into Sanskrit, the one usually photographed with scrolls, Gors, Pandits, the ones that much later often derogatorily referred at Byechi Bhattas (?) or Begging Class Pandits). Besides that there were minority called Buhur, or the Trader Class, someone more likely to take up a trade like clothselling.

-0-

Still laughing, one of the kids put his arm around the other kid’s shoulder. While taking a stroll on the Island, the two brothers in arm together start singing a devotional sing.

‘MAa SHera WAliyay, TEra SHer AAgaya!’

It was the opening line from gut-busting Akshay Kumar number from year 1996 film ‘Khiladiyo Ka Khiladi’. Hero’s brother is about to be bumped off by the bad guys, our hero gatecrashes the Jagrata party of Villainess and as precursor to his convoluted plan for rescue his brother, sings, ‘MAa SHera WAliyay, TEra SHer AAgaya!’, ‘O Tiger Riding Mother, Your Tiger Has Arrived.’

Mock singing over, the two boys break into guffaws. Their Parikrama of the island is over, on the way out, over the footbridge, they spot a Babaji, a veteran of Amarnath Yatra. The two friends decide to test him. Shooting straight, they ask him one of the most elementary question that has baffled the greatest of human mind:

‘Bhoot Hotay Hai. Bhoot.’

‘Do Ghosts exist?’

Baba, perhaps thrown off by their accent, or perhaps evading the question, replies, ‘Avdhoot. Avdhoot.’

The boys repeat their question, ‘Bhoot Hotay Hai Kya. Bhoot.’

Baba repeats his cryptic answer,’Avdhoot. Avdhoot.’

At this the boys break into more laughter. An arm over each other’s shoulder, marching toe-to-toe, humming something, the two walk out of the island and back to their homes in the surrounding village. The babj proceeds to pose for the camera.

-0-

| Strange Tales from Tulamula Fish.

|

| Syen’dh at village Tulamulla. River originates in Gangbal-Harmukh and is not to be confused with Sindhu or Indus River. |

The feeling was that of disorientation. As I entered the Island, I was lost in some old memory of the place. A fleeting vision. And then I was lost, really lost. I somehow got separated from rest of the pilgrims that included my parents and relatives. None of them were in sight anymore even though we were all walking together moments ago. In front of me was an iron grilled door, but I didn’t know if it was the entrance or the exit. Towards right, I saw a security building and for some strange reason assumed that everyone must have gone inside it to get registered or something. I felt like staying lost for sometime more. I sat down at my old spot, little stone steps next to the footbridge over the stream that surrounds the island. And I scratched that old memory out:

I walked between innumerable pair of legs to get out of the frenzied melee around the spring. That sight: a man standing on a wooden plank over the milky whiteness of the spring, a bridge to the island, a bridge between deity and devotee, it was unnerving. It was like watching someone rope walk only there was no rope, only a piece of wood. Did the Priest, the conduit on this precariously placed plank know how deep the white spring went? How many meters below the level of flowers? All the pushing and shoving was getting a bit too much. What if I fell into the spring. Holy or not, I had no plans of measuring the depth of the spring. And one can barely see anything in this rush. I walked between innumerable pair of legs to get out of the frenzied melee around the spring. I went back to the stream. The devotees were still taking dips in its cold, dark waters. Even the thought of its water scared me. Earlier in the day, I had escaped the compulsory ritual bath thanks to my little drowning incident in the swimming pool of Biscoe. I was still a bit traumatized, even though it had been more than a month now. I told everyone in clear terms that I was never going into water ever again in my life. Now I sat on muddy, half broken and slippery steps that lead into the dark stream. I chose the spot next to the footbridge that connects the island to the village. There were people diving into the stream from the footbridge and there were kids my age frolicking in water, swimming. In the swimming pool, other kids had been holding onto a side bar with their both their hands while paddling their both feet in a synchronised. They was practising swimming. I learned drowning. I missed that little detail about holding onto something and started paddling my feet without holding onto anything. After I was pulled out of water by a Ladhaki instructor, I found myself in middle of the pool and I was still paddling. I had gulped down a good amount of water. I believe I would have died had I stayed underwater a bit longer. Or, maybe not. The instructed carried me to the side before the judge of my performance, the class teacher. I pleaded with the teacher to have me pulled out of the pool. I told her that these waters were going to kill me, that I was going to die. She calmly pointed at her watch and said there were still twenty minutes for the period to be over, there was still time. I cried. I held on to those sidebars for rest of the twenty minutes. On the ride back home, standing in the school bus, I vomited green water. My underwear was wet, it stuck to my skin me like an insult. I had completely forgotten that our class was to going to have swimming lessons starting that day and that we were supposed to bring a towel and an extra underwear to school. What stupidity! On reaching home I told my grandmother, I was never going back to that monstrous school. I laughed to myself. Swimming is for fish.

I noticed little black fish swimming in the shallows where the waters met the stairs. They would swim to the stairs and then swim back. I threw little pebbles at them, just to wake them up, to watch them swim. I always liked fish. I named my grandmother’s sister, Machliwalli Massi, only because her house at Rainawari overlooked Jhelum. The first time my grandmother wanted me to go to her sister’s place, I wanted to know if I could see fish from some window of the house since it was on the river bank bank. She said indeed I will. I was disappointed, no fish from the window, even the river was a bit far from the house, it wasn’t on the river, but there was some beauty to it, and the name stuck. She remained my Machliwalli Massi even after her family moved to Jhallandar. Even as she lost her memories to old age.

|

| A devotee praying on one leg. Summer 2008. |

-0-

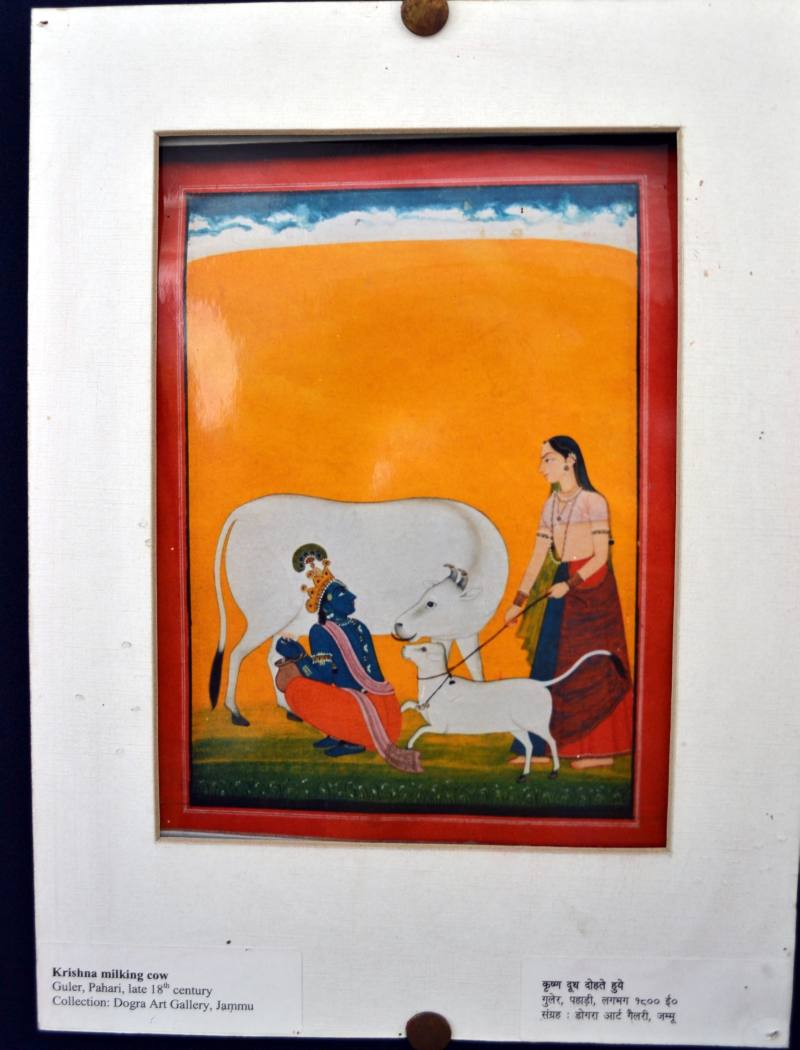

From miniature art painting exhibition at Kala Mandir, Jammu.

|

| A re-creation of this one and a couple of more were featured in J&K Bank 2008 Annual Calendar |

-0-