Guest post by Rekha Wazir. She recalls how her Grandfather, Tara Chand Wazir came to be the first Kashmiri to fly in an aeroplane in 1921.

Continue reading ““The Intrepid Kashmiri in the Flying Machine” by Rekha Wazir”

in bits and pieces

Guest post by Rekha Wazir. She recalls how her Grandfather, Tara Chand Wazir came to be the first Kashmiri to fly in an aeroplane in 1921.

Continue reading ““The Intrepid Kashmiri in the Flying Machine” by Rekha Wazir”

|

| used in Quint |

Continue reading “Portrait of Mahrattas, KP family, Brariangan, 1950s”

|

| Hari Parbat Hill Map, Drawn on a Shawl, 1850s. |

Information that is easily available online:

Info. not often mentioned (however recalled by poet Zareef Ahmed Zareef):

Continue reading “Devi Angan Conundrum: History and Making of Hari Parbat Temple”

A few lived it, many died and some waited. His last words were, ‘Where is Home?’

Refugee Camp, Jammu Province, 1990’s…

It was a sea of people. Hundreds of trucks were lined up; each carrying a home. I remember the day when one man lost his life to the blazing sun in the afternoon. He lived in our block. He was forty. He earned his living by binding books. He was playing cards on the roadside. Feeling dizzy he left in between, and fell panting in the middle of the road. People offered him water. He died instantly.

Pitambar Nath’s body was found on the banks of the river Tawi. He was cremated the same day at Devika Ghat. The next day we woke up to cries from the block adjacent to us. The temple was flooded with men and women. I saw an old man’s body wrapped in white cloth lying on the floor. He was being washed. A priest was chanting hymns. People were offering water to the dead. Gash Nath died due to electrocution. A high tension wire ran close to his quarter. The chant asking God for forgiveness reverberated in the entire camp. ‘Kshyantavue maiaprada shiv shiv shiv bho shree mahadev shambu’. The man who works at the crematorium says, ‘We mostly receive bodies for cremation from refugee camps.’

***

The whole camp is engulfed in a silence of despair and longing. A house with several rooms lies vacant in the village. Fifteen families have sought refuge in Narayan temple near the camp. Some live in sheds and fabricated structures alongside the railway station. One old woman is hurling abuses in her native language. She is sweating profusely. Her husband is continuously stamping the earth with his feet. He shouts at the sky, ‘This is galling, this is galling.’ He does this all day.

People are dying in numbers. The one in E-1 died of a snake bite. Hriday Nath succumbed to fever. One of the teachers from the Government School lost hold of himself. A week later, he left and never returned. Some say he was last seen at the crematorium and then at the bus stand. Did he ever board the bus to his home? Is he alive? Nobody knows.

***

The camp welfare association has been formed last night. Trilok Dhar will be taking us to the commissioner’s office. He has a few contacts. People taking refuge in Geeta Bhawan will also be joining us. Have you received the ration? They are giving 5 kilos rice to each family. This is the ration card. It has my permanent address. This is all what is left. We must carry it along with us every time. This is our identity. They are going to shift us to a different camp. It will be on a hilltop. Where are you going? You must not go out. The sun has come out early in the morning. Be with us for a few days. We will talk.

Niranjan Kak with a frozen flickering smile: I’ll take a walk over the wooden bridge. I’m feeling a bit perturbed. I have to take care of my cows. The fields have been left unattended. The garden is in complete disarray. Let me call Jigri. Where is Vijay? Where is Asha? What’s with the walnut tree? Why has it dried? Who has stolen the fruits? Look at the frozen sky. The river has changed its course. Someone has set my house on fire. It’s burning down to ashes, the house of my ancestors. Look at the mound of the dead. I must leave. I have things to do.

He lived alone in the camp in a shabby room covered by cobwebs. He mostly seated himself on the bed and at times on the wooden chair alongside his bed. The picture of his native house always lies close to him. It is not a dangerous illness but the memory of home that torments him for days and weeks. The sobs slow down when the darkness sets in. Nights are filled with shrieks and native songs.

I remember the way to my home, 200 meters from the bridge, near Farooq’s bakery.

‘I nurture my longing and see through days. I will wait. They say we will be taken in buses. I have packed everything. When are they taking us back? I make amends with my heart. I caress it. My heart starts throbbing violently when I visit the place. I tremble and run back. Look at the stream of tears flowing through my eyes. I have grown bitter over the years. I am losing my memory. It’s something like a bridge which hangs above the desert. The bridge shakes every second. It’s not fixed. One has to crawl to reach to the other end. It changes position. Many fell down and died. The old man and the woman couldn’t hold for long and jumped to death. I persisted for days and years. Hundreds died. Bridge remains. It hangs. It devours. I escape. I run. Horses cry, make sounds and gallop towards the bridge. I mount on a horse and take the route through mountains. I jump from mountain to mountain, peak to peak, into the valley of mountains and then towards a vast emerald blue sea spanning the entire universe. I have grown lonelier. Solitude is eating me up. Where have they gone? Who is jeering on the streets?

***

Where are my cigarettes? Have I turned a little sallower on face? No. Am I sweating? Yes. Who started this carnage? They. Who will stop this conflagration? Where are the firefighters? I’ll wait till my final breath. I have tumors in my stomach. It refuses to take food. I bark like a dog. There is mud all over on the sky. It’s on my face. There is no light. One day I will die in sleep. That must be liberating. Death will be my final emancipation. Deliverance.

Do you sense this turmoil in my heart, this devastation? Who can save this exile from dying in an alien land amidst strangers? Nobody! Waiting seems like dying, dying every day. Where is the priest? He is out for the tenth day at Ranbir canal. Who died? Bansi Lal from Block Q. How is Hriday Bhan? He is suffering from lung cancer. He pleads with God to give him death. How is his wife? She died a week back.

Have they cut down all the trees? There are no trees. This is desert. Where is the harvest of this season? Who stained it with blood? I wait for the return of winter. What’s with the sun? Who has fixed it over my head? Why is it not moving away? This is summer. Where are the hillocks? This is desert. Why is the window pane shut? There are no windows. Who will cry when I will die? Nobody. What to do with these memories that have accumulated in my heart? They assail me. Give them to fire. What to do with the dreams? Starve them. How many summers are waiting? My guts have dried. Water them.

Everything will be turned to ashes. Every one of us will die.

***

Who is groaning?

It’s him. He is trembling, another paroxysm of yearning. He is breathing heavily. Yes, he is alive. He lives.

Where is the photo frame with the picture of his house?

He flings it out.

Give it to him. Tell him, ‘The bus will come in an hour’.

I heard, ‘They are shifting us to another camp. People are already on the move. The place is around cement factories. Slum. Desert. Brick kilns. I am tired of moving from one camp to another camp. Where is home?’

Why these breathless, dreary sighs? Death is near. It has been set in motion. We will die like dogs. Look at them. They are galloping towards us. It’s a mob with swords and guns. Run!

Niranjan Kak is writing names on a paper. It is his permanent address. The place has been burnt. The house was looted. He wears pheran in summer. He has a long beard. The photo frame with the picture of his house hangs from his neck.

‘I will wait on the bridge for the whole day. I will wait for the fires to ebb. It is not that everything stands destroyed, that everything is in ruins, a memory still breathes, a laugh still resounds in the rooms, a house still stands tall and the earth still bears my footmarks. Flowers have dried and trees have picked a disease. Time has wilted them. They long for water.’

I haven’t locked my room and wardrobe. They have plundered it. The new pillows still lay on the bed waiting for my father to rest on them. My mother isn’t doing well. She has fever. I’ll go to the town to collect some medicines. My radio and new books are in the almirah.

***

He is on his bed now, muted. He doesn’t speak to anyone. He has stopped eating. He walks inside his room, making a circle every minute. He never comes out of his dwelling. He fears sun. He waits for winter. He waits for homecoming. He has grown weary and old. He has long hair and beard. He lays famished on his bed. His eyes are fixed on the ceiling. He wears a vacant look. He doesn’t blink for hours. He hides the pills and other medicines under his pillow. The chemist nearby the camp visits him every week and feeds him intravenously. He offers a faint cry, a wail every morning and evening.

What is life to me and what is its meaning? It’s a long tiring wait. It is futile. Flakes of snow welcome me at the door. Who lights the lamp? Smell the incense and see the rising embers. Where has the mystic gone? What’s with the people? Why have they gone mad? Who has killed Janki Nath and Bimla? Where is Ramesh? Everybody has fled. I hear gunshots. Do you hear? A mob is coming towards our house. Do you hear their slogans? They have taken a vow. Every one of us will be wiped away. There will be massacres. They are coming. They will kill us all. Where is Home?

He has grown hysterical and his memory keeps tormenting him.

Why are the trees bereft of their fruits? What has happened to them? Time has poisoned them. Desert has grown on snow. They grow only leaves and stems, no flowers. Where are the birds? What is with the water? Who has changed its color and its sweetness? It has become sour and frothy. What has happened to the village and its houses? Who has lived here? Who has left them? Who wails inside them? Where are the children? What memories they hold? Who cries all night? Let them stone me. Where should I go? I’ll bury myself in the walls or I’ll dig a sepulcher for myself. What’s with the fire and its flame? Who is dousing it?

I am reminded of a path that was all laden with grass and mist with dense woods. Now it’s only stones. I see a river passing by, a flock of sheep dotted with different colors, walnut trees, rice fields, clear sky and a thud of cold breeze floating on chinar leaves. I am reminded of the giant folding of mountains guarding our village. These are spherical dwellings, hovels. It is a new place. The house stands buried now. Bricks have turned into dust.

***

The next day I visited the engineer to borrow the almanac from him. He was preparing his bed, covering it with white bed sheet, two pillows at the head end and one at the other. He hurriedly allowed me to come in. He was delighted at the sight of seeing someone visiting him. He smiled with a sparkle on his face. I asked for almanac. He offered me tea. I shifted my gaze. A sour odor wafted in the room. Nauseating. The place was reeking. A strong stench emanated from the room. He had placed a kerosene stove on bricks. There were few utensils. A large portrait of a Goddess. A family portrait. Scraps of paper all over, each having the same thing written over, the address. Table Fan. A kerosene lamp hanging from the nail above a small wooden shelf. Ration Card. Books. A dusty mirror and a round comb. Ashtray. Cigarette stubs. A soiled sheet lying on the floor. The smell of quilt and mattress. We had our tea. He mentioned places and names. There were moments of silence.

‘I don’t believe in God, I believe in death, I saw many. I saw water turning black. I saw ghosts pillaging everything in their way. It is only between me and the flames. Only time will decide who will consume whom?’

‘The blood soaked hands rise in the dark, circling my neck. I lost them all. I’ll not survive this sweltering summer. I’m all dry. Parched stomach. This darkness is eating me up. I’ll die in disquiet. I vomit. I shiver. I breathe heavily. I have nausea. This is not home. I have been dragged here. I don’t belong to this place. I’m suffering today. I’ll suffer tonight. I’ll suffer tomorrow. It’s a vale of sufferings. I’m dying. I’m waiting for the winter. I’ll go home. I’ll die there. I’ll suffer there, but not in solitude. My stomach is long dead. The food is floating. My mouth is stinking. I can’t bear the stink. What will I do? I will stop my breath.

‘Winter has arrived. Bring me some snow, snow in round earthen vessel. It will not melt. Bring me some snow. I will touch it; I’ll let it melt in my hands. I will stand still when it starts snowing.’

He stopped in the middle of the conversation, something came upon him, and he started murmuring to himself, looked at me in an instant and started crying like a child. He rose from the bed and fell on his knees pleading with me to take him to his native home. ‘Take me. Take me to my home. I have money, I’ll spend it all. Take me to my home. I will kiss the walls of my house. I will die anytime. The sun is eating me. I haven’t slept for a week. This heat is charring me. Take me to the commissioner. Take my ration card and show it to them. This guy knows me. He is from our village. His father was my friend. He will arrange a taxi for me. Write a letter to the Government. Have this diary. Call my friend. He will take me home. Where have they all gone? She is here with me all the time. She loves strolling with me in the garden, walking down the road, and leading to the river gushing through the village. We sit for hours on the banks of the river. She dips her long hair in the water and waits for the sunrise.

‘I will walk close to that mountain surrounding the entire village. They say the river has reduced to a thin quiet stream. The river has dried. I will follow the stream. I will wait for the water to turn sweet. The wait is tiring. I lived life in solitude. I don’t die either.’

It was in the summer of the year 2000; Janmashtami festival was being celebrated in the camp. The temple was all flooded with devotees. A rather pale cloak of darkness had descended on the morning. The earth had lost its smell. He was in the middle of eating his lunch. The glass of water had spilled over. There was rice spattered all over his bed. His fingers were clenched tightly with one hand holding a fistful of rice. The tip of his tongue had come out, bruised and marked by streaks of blood. His mouth was half-filled with food. The eyes were dry and clear; a tear had rolled down his cheeks. His face looked as if marred by enormous grief and the picture of his native house hung from his neck. He was dead, lying on his feces. Ashen legs, blue swelled veins, bloated belly, blanched shaven glistening face and combed hair. His eyes gave me a long gaze. Niranjan Kak, the engineer was no more. I opened the pack in a hurry and smoked half of them. The other half I kept on his bed and went away.

The chanting continued… ‘Kshyantavue maiaprada shiv shiv shiv bho shree mahadev shambu.’

Notes:

1. Tawi: A river in Jammu Province in the state of J&K.

2. Devika Ghat: Name of a crematorium.

3. Pheran: Traditional Kashmiri attire worn during winters.

4. Janmashtami: Hindu Festival celebrating the birth of Lord Krishna.

-0-

This piece was first published in Muse India, Issue 70.

Sushant’s work has been published by Outlook, Kitaab, Bloomsbury, The Bombay Review, Muse India, New Asian Writing, Coldnoon and others.

-0-

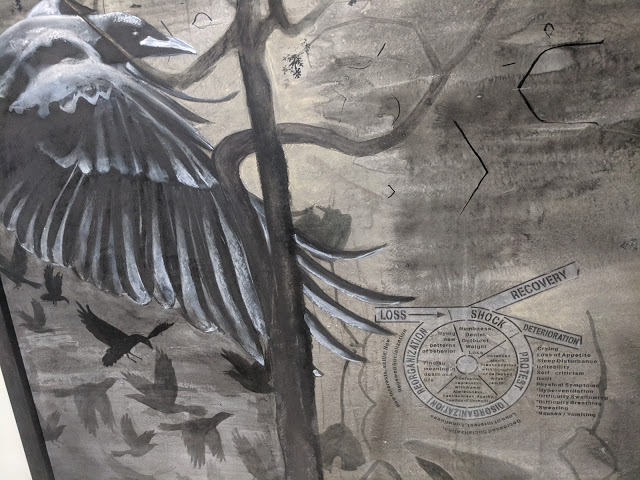

Artwork: Vinayak Razdan

A look at the whirling ritual among KP women and a possible link to Kashmir Shaivism. Why do KP women dance in circles at certain special occasions? Touching the tip of an iceberg here.

“She brings pressure to bear on the seed in order to separate the oil from the husk, she who, in the [midst of these wives], is Kundalini. As mistress of the ‘three-and-a-half’ tradition, she while standing on the ‘bulb’, circulates everywhere.”

Mayen dree chay Dyakas grih mutchraav

i beg you, unwind sad lines of your forehead

yoot chasman andar tche aab chuna

water in your eyes has dried, has it not?

chyen dree zaenith be chus khamosh

I swear on you, I know, yet I am silent

na kya zan me’nish jawaab chuna

not as if the answer, I don’t have

Dil ratchun fitratan me aadat chum

to nurture heart, this habit, is my nature

Dil bajaey wanum sawaal chuna

a happy heart, is a question, is it not?

Jaanbaazaz asar novi saazas

Jaanbaz’s music casts a potent spell

nati prathkeasi’nis Rabaab chuna

else everyone has a Rabaab, is it not?

~ Ghulam Nabi Dolwal “Janbaz” Kishtwari, Singer-Lyricist-Poet

I witnessed this scene at Kochi Biennale in March, 2019. A girl was looking for her family house in an installation by Veer Munshi titled “Pandit Houses”. She called up someone on the phone and asked them if they recognized. She was hoping to see it there. It wasn’t. “All of them look similar”. I later talked to the girl and found that she had traveled from Chennai.

|

text at the exhibit:

A Root-less Tree

by Santosh Shah ‘Nadan’

Tr. from Kashmiri by Aman Indra Kaul

Where have I left to, where have I come to

In all corners has home’s love sunk to

What do I tell thee, what have I been through

Pick up your pens, elegies should you write

Hiding our identity, left we our homes

Weeping us, abusing they, left we our homes

Exile is extirpating a chinar from its roots

When does a wasteland reap verdure

Sown to its own home, it springs furthermore

Ramayan’s end is now its start

Gone have Rishis from the valley too

Dashrath finally, but had to die

Waiting for final rites, parched, he died

I, from birth, built a home like an ant

Like a thief, I, a raazbaa’e left home too

Having lost its way, where do I head to

In front of home were Sangrishi, in front Rishimoal

When do I run to wash my Saptrishi’s feet

Why division of humans when we all were one

Ganeshbal, Tulmul, Shankaracharya, Silgam

Amarnath, on its head, sitting like a chief

Lokutpur, you know, was my all-time abode

Nund Rishi, Sadarmaej, Mangladevi sthaan

Uintpore astaan, with what feet do I go there

Who will take taher on chodish to Zaala

How do I start towards Nilnaag Omoh

And a far-off place where ‘Amir’ lives

How do I reach Mukdoom Sahib and to Sharika

Where’s my father’s home and my in-laws’

Where are neighbours and childhood buddies

Who’s gonna go to Vomaaye on gang’e atham

Where be our Koshur and its culture

Where do I breathe under Chinar’s shade

Where do I relax with kangri and chai from Samavaar

Don’t change colours, don’t you Kashmiri Pandits

Tread truth’s way and don’t you fall fake

Think what waste has exile turned us into

How do I forget the rishi’s abode—

the home of sufis and saints

Kashmir, I tell you,

the ‘Nadan’ of Chandigam is devoted to you.

Notes on Translation:

Translated from Kashmiri. In its original form and language, this poem is very lyrical at most junctures. While translating, with whatever little I could, I tried to keep the flow as much as possible however pressing harder on rhyme would have lead to loss of meaning.

I had Rushdie in mind while translating. I wanted the Koshur in it to remain. Maybe, for posterity, like ‘atham’ to be remembered not as ‘ashtami’. So I left some of it unturned.

Because I was born in Delhi post exile, I don’t have the total grasp on the language and its dynamics. It is very much possible for me to misunderstand a word, a line or a stanza. Hence and otherwise too, I’m all in for constructive criticism.

— Aman Indra Kaul

Kyati Draay yor kot roznay aaye

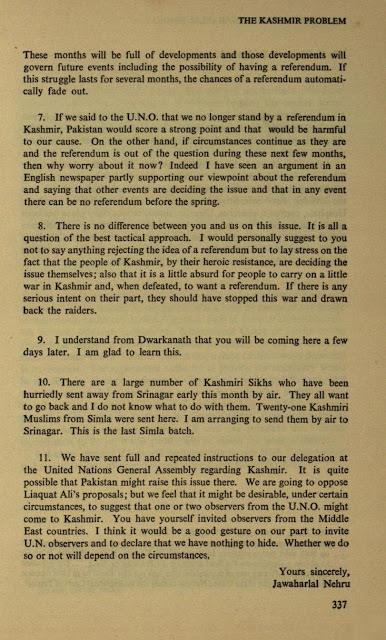

Dwarkanath [Katju] writes to me that there is strong feeling in the leadership of the National Conference against referendum. I know this and quite understand it. In fact I share the feeling myself. But you will appreciate that it is not easy for us to back out of the stand we have taken before the world. That would create a very bad impression abroad and more specially in U.N. circles. I feel, however, that this question of referendum is rather an academic one at present. We have made it clear and indeed it is patent enough that there can be no referendum till there is complete peace and order in Kashmir State and all the raiders have been pushed out. As far as I can see this desirable consummation will be be achieved for some months yet. In the Pooch area it is quite possible that these raiders might continue to function in the hills and it might not be worthwhile for us to make a major effort to push them out during the winter. Thus for some months the question of referendum does not arise in any practical form.These months will be full of developments and those developments will govern future events including the possibility of having a referendum. If this struggle lasts for several months, the chances of referendum automatically fade out.If we said to the U.N.O. that we no longer stand by a referendum in Kashmir, Pakistan would score a strong point and that would be harmful to our cause. On the other hand, if circumstances continue as they are and the referendum is out of the question during the next few months, then why worry about it now? Indeed I have seen an argument in an English newspaper partly supporting out viewpoint about the referendum and saying that other events are deciding the issue and that in any event there can be no referendum before the spring.There is no difference between you and us on this issue. It is all a question of the best tactical approach. I would personally suggest to you not to say anything rejecting the idea of a referendum but to lay stress on the fact that the people of Kashmir, by their heroic resistance, are deciding the issue themselves; also that it is a little absurd for people to carry on a little war in Kashmir and, when defeated, to want a referendum. If there is any serious intent on their part, they should have stopped this war and drawn back the raiders.

~ 21 November 1947. Nehru writes to Sheikh Abdullah on murmurs inside NC against referendum. These guys knew as long as Pakistan was the aggressor there was going to be no referendum. For them it was just an academic exercise.

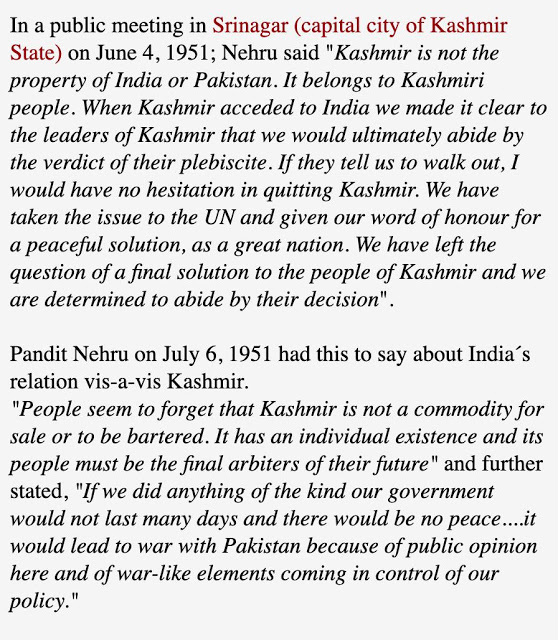

“you hinted at Kashmir being handed over to Pakistan…if we did anything of the kind our Government would not last many days and there would be no peace…It would lead to war with Pakistan because of public opinion here and war-like elements coming in control of our policy. We cannot and we will not leave Kashmir to its fate…The fact is that Kashmir is of the most vital significance to India…[H]erelies the rub…We have to see this though to the end…Kashmir is going to be a drain on our resources, but it is going to be a greater drain on Pakistan.”

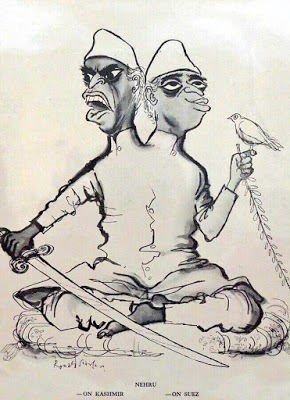

Ronald Searle’s Nehru cartoon. Punch Cartoon. 1957. Peacekeeper in Egypt, asking for UN and US intervention. Painted Warmonger (like Modi) when it comes to Kashmir. All driven by world politics and individual interests of power countries.