Fable of Kashmiri Beauty as told by Francois Bernier

Fable of Kashmiri Beauty as told by Francois Bernier

“If woman can make the worst wilderness dear,

What a heaven she must make of Cashmere!”

– Thomas Moore

Marco Polo (1254 – 1324), famous trader and explorer from Venice who was one of the first western travelers to walk the Silk route to China, during his brief visit to Kashmir noticed:

“The men are brown and lean, but the women, taking them as brunettes, are very beautiful”

A footnote accompanying these lines in The Travels of Marco Polo, Volume 1, 3rd edition (1903) goes on to quote Francois Bernier on the subject of Kashmiri beauty. And in turn, Francois Bernier’s Travels in the Mogul Empire, edited by Archibald Constable (1891), goes on to quote the above lines of Marco Polo.

Footnotes, of course, never tell the entire story, but they do point to the stories already told.

Francois Bernier (1625 – 1688), French physician and traveler, during his visit to Kashmir in 1664–65 as part of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb’s entourage, had written:

” The people of Kachemire (Kashmir) are proverbial for their clear complexions and fine forms. They are, as well made as Europeans, and their faces have neither the Tartar flat nose nor the small pig-eyes that distinguish the natives of Kacheguer (Kashgar), and which generally mark those of Great Tibet.”

Bernier wrote a number of letters during his travels in India. These letter, originally written in French and meant for various people he knew, were later translated and printed by various publishers in a book format. The first one was published in 1670 and created great interest in the west. Subsequently, Travels in the Mogul Empire By François Bernier, Translated by Irving Brock was published 1826. In 1870 came Voyages de François Bernier ( in English language as Travels in the Mogul Empire), and in 1891 Travels in the Mogul Empire, edited by Archibald Constable.

These books for a long time the only authoritative source on description of Kashmir.

Bernier wrote about Kashmir in a series of nine letters written to one Monsieur de Merveilles. In a sense, these letters of Bernier were quite unique and a first: although before Bernier some Portuguese Jesuits, having the patronage of Mughal court, had been to Kashmir*. Due to the early descriptions of these Jesuits, an interest in ‘Jews of Kashmir’ and even the people receiving Bernier’s letters wanted more information about the subject.

Bernier who is widely regarded as the first westerner to have described Kashmir in details that covered people, culture, geography ( complete with a map), history, myths and religions of this region.

Mughals thought of Kashmir as ‘Jannat‘ or ‘Paradise’ and on publication of Bernier’s letters, naturally, Kashmir was covered under the title of Journey to Kachemire, The Paradise of the Indies. Having lived among Mughals, Bernier, on the subject of Kashmiri beauty, further wrote:

“The women especially are very handsome; and it is from this country that nearly every individual, when first admitted to the court of the Great Mogol, selects wives or concubines, that his children may be whiter than the Indians and pass for genuine Mogols. Unquestionably there must be beautiful women among the higher classes, if we may judge by those of the lower orders seen in the streets and in the shops.”

More often than not, all subsequent European visitors to Kashmir were to quote from Bernier’s letters these very lines that sing odes to Kashmiri beauty. As footnotes, these lines filled the margins of a majority of early books that enticingly described Kashmir and introduced western readers to its splendor. Irish poet Thomas Moore (1780 – 1852) was one of those early readers of these letters. His famous Oriental poem Lalla Rookh (first published in 1817 and whose publishers in footnotes did indeed quote Bernier on Kashmir) went on to introduce many more western readers to the fabled land of exotic beauty – Kashmir.

What most of these footnotes did not mention was how Bernier came to have such an informed opinion on the subject of Kashmiri beauty.

Bernier, it seems, was an inquisitive traveler, more so when it came to the topic of beautiful women. For beautiful delights he employed beautiful “stratagems”.

In Lahore, a city (then and perhaps still now equally) renowned for the beauty of its women, Bernier employing an “artifice” picked up from the Mughals, went around following elephants, particularly the ones “richly harnessed”. The reason for this seemingly absurd act: As the elephants with silver bells hanging around both their sides went tinkling by, women invariably “put their heads to the window”. The stratagem must have been a success since he thought women of Lahore to be “the finest brunettes in all the Indies, and justly renowned for their fine and slender shapes”.

In Kashmir, for lack of a better method of “seeing the fair sex”, he employed the same method to amuse himself. But, he wasn’t satified with the method. An old ‘pedagogue’ with whom he used to read Persian poets later devised a better technique for him. The old man had freedom of access to no less than fifteen houses; Bernier spend some money to buy sweetmeat and accompanied the old man to these houses. Bernier pretended to be old man’s newly arrived relative from Persia having come to Kashmir acquire a bride for himself. He distributed sweets to children and soon:

“everybody was sure to flock around us, the married women and the single girls, young and old, with the twofold object of being seen and receiving a share of the present. The indulgence of my curiosity drew many roupies out of my purse; but it left no doubt on my mind that there are as handsome faces in Kachemire as in any part of Europe.”

Now we know why his opinion on beauty of Kashmiri women was so widely accepted. Later year travelers who disagreed with his high opinion of Kashmiri beauty, travelers who felt cheated, who felt mislead (one French traveler was so disturbed by what he saw that he called the women of Kashmir “hideous witches”) were of course not inquisitive enough to apply Bernier’s stratagem for seeking beauty.

Many travelers to Kashmir were to second and third Bernier’s opinion on Kashmiri beauty, and never did they (or rather their editors) fail to mention Bernier’s words in the footnotes.

While much has been made of his words, however, these were not the last words of Bernier on the subject of beauty of Kashmiri women.

Bernier, with his background as a physician, was no doubt a curious traveler. In describing his twelve-year journey to places like Persia, India and Egypt, he never fails to mention the women of the far and distant lands that he is visiting. His fascination with human form and skin, even if most of the time it was just fascination for female form and female skin, came to a logical conclusion in the year 1684. In this year, he anonymously (although from the content of the article his name could easily be fathomed) authored an article in the Journal des sçavans titled Nouvelle division de la terre par les différents espèces ou races qui l’habitant (“New division of Earth by the different species or races which inhabit it”). This article is widely regarded as the first work that distinguished humans into different races. He distinguished human beings mainly on the basis of their physical characteristics especially skin color, although with no hierarchical distinction between them, into four (five) races: Far Easterners, Europeans, blacks and Lapps, and about American Indians, he was unsure.

In the article, having discussed division of humans into different races, Bernier seeks reader’s attention for his favorite study subject: female beauty. Bernier recounts tales of all the female beauties that he encountered during his travels and describes them in all their glories; even pits them against one another. He talks about “very handsome ones from Egypt” who reminded him of “beautiful and famous Cleopatra”; he talks about “blacks in Africa” who could “eclipse the Venus of the Farnese palace at Rome”; he talks of “beautiful brunettes” of Indies; he talks about Indies girls who when yellow look like a “beautiful and young French girl, who is only just beginning to have the jaundice”; he talks about “esteemed” women who live by the “Ganges at Benares, and downwards toward Bengal”; he talks about brown women of Lahore who though “brown like the rest of the Indian women” to him seemed more charming than all the others and talks about their “beautiful figure, small and easy” that surpasses “by a great deal” even “that of Cashmerians”; and about the Kashmiri women he wrote:

“[…] for besides being as white as those of Europe, they have a soft face, and are a beautiful height; so it is from there that all those come are to be found at the Ottoman Court, and that all the Grand Seigniors keep by them. I recollect that as we were coming back from that country, we saw nothing else but little girls in the sort of cabins which the men carried on their shoulder over the mountains.”

These lines, now, read like a footnote to some of his earlier exalted work on the subject of beauty of women. Nonetheless, even these lines were to become part of folklore among travelers to Kashmir.

-0-

* Jesuits priest Jerome Xavier (great-nephew of famous Roman Catholic Christian missionary Francis Xavier) is widely regarded as the first European to have visited Kashmir. In around 1597, Jerome Xavier and Brother Benedict de Goes visited Kashmir on invite of Mughal Emperor Akbar and Prince Salim (Jahangir). Akbar, after having added Kashmir to his burgeoning Empire, was to visit Kashmir twice or thrice during his life-time. Letters of Jerome Xavier (published in around 1605 A.D.) were the first to introduce Kashmir to Europe.

-0-

Bibliography:

The Travels of Marco Polo, Volume 1, 3rd edition (1903) of Henry Yule’s annotated translation, as revised by Henri Cordier; together with Cordier’s later volume of notes and addenda (1920).

Travels in the Mogul Empire, edited by Archibald Constable, (1891)

-0-

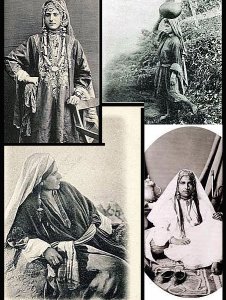

Images:

( left to right)

photographer unknown, Kashmiri women, 1910 (found at Kamat.com)

Fred Bremner, A Village Girl, Kashmir , 1905

Fred Bremner, A Panditani [Hindu] Kashmir, 1900

John Burke, a nautch girl from Kashmir named Azeezie, 1862-64 (These three are from Harappa.com)

-0-

This is Page 1 of the series Fables of Kashmiri Beauty

-0-

Rest of the pages:

- Fable of Kashmiri (not so) Beauty as told George Forster: page 2

- Fable of Kashmiri (un) Beauty as told by Victor Jacquemont: page3

- Fable of Kashmiri Beauty (yet) as told by G.T. Vigne: page 4

- Fable of Kashmiri beauty (types) as told by Walter Lawrence: page 5

- Fable of Ugly Kashmiri as explained in a Magazine: page 6

- Fable of Kashmiri Beauty (generally) as told by Younghusband: page 7

- Guide to the Fable of Kashmiri Beauty as given in a Tourist Book: page 8

-0-

(Link: For those interested in getting these books on kashmir for free)