William Carpenter Junior(1818-1899), London born water colorist son of a portrait painter

Margaret Sarah Carpenter, came to India in 1850 to draw people and scenery. In 1854, he came to Kashmir, staying for a good enjoyable year till 1855, producing some of his best works. William Carpenter Junior returned to England in 1857 and exhibited his new Indian paintings at the Royal Academy where they stayed on display for the next eight years. Many of these paintings were also reproduced in The Illustrated London News as special supplementary lithographs.

Following are two Kashmir drawings by William Carpenter Junior published in Illustrated London News, June 1858

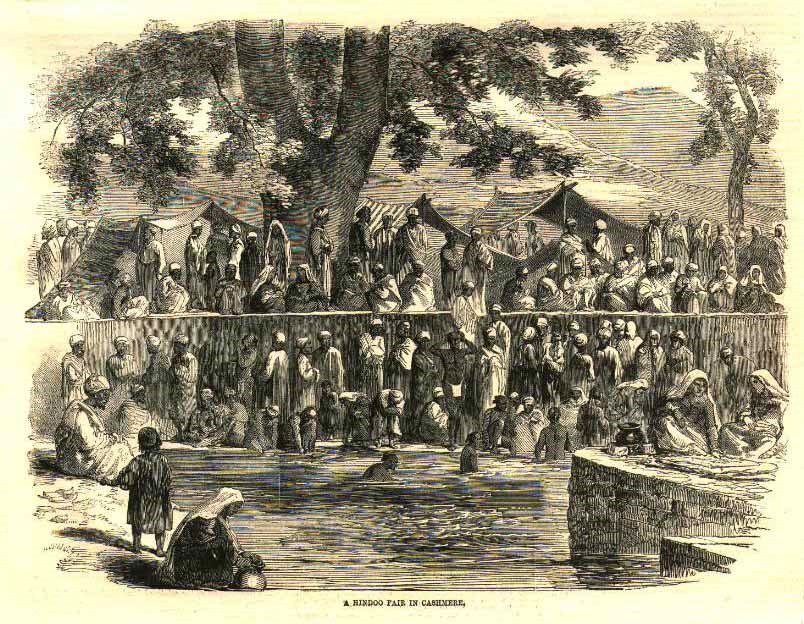

Caption: A Hindoo fair in Cashmere

[Update 2, Augm 2018: I finally managed to acquire the original image. The accompanying image makes it clear that the above image is of Jwala Ji shrine, Khrew. It is now obvious that the water body depicted is the spring at the bottom of the hill. ]

The caption for the drawing does not mention the location of the fair but without doubt this fair was held at the Khir Bhawani Spring located at Tulmul village in Ganderbal district of Kashmir.

This drawing presents the scene of Pandit pilgrims performing the ritual of purification bath in the ice cold waters of the stream that surrounds the holy island. The stream is called Syen’dh in Kashmiri (and originates in Gangbal-Harmukh ) and is not to be confused with Sindhu (Indus) River. In older days, the pilgrims mostly used to reach the island spot in boats, doongas and wade through swamps and marshy lands. The perspective of the drawing reveals that William Carpenter was looking at the island from across the stream. In the background of the drawing, one can see the camp tents of the pilgrims pitched on the central island under the shade of chinar trees. The fair is still held annually in the month of June with the pilgrims camping out at the wonderful location for days.

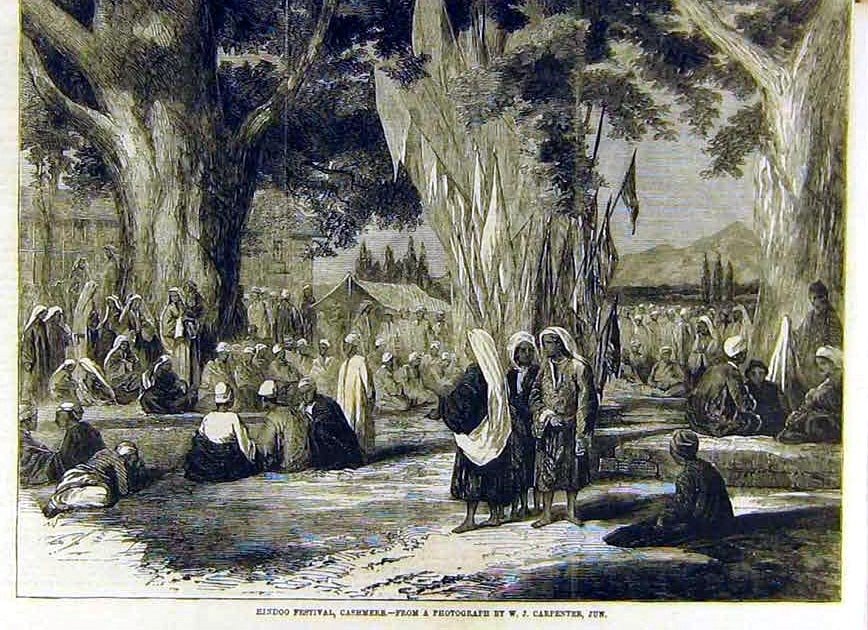

Caption: Hindoo Festival, Cashmere – from a photograph by W.J Carpenter, Jun

In this drawing we can see Pandit men and woman sitting, surrounded by chinar trees, around the sacred spring (not visible but its end corner marked by flags and staffs*). The scared spring (naag) is believed to be the manifestation of an ancient goddess, who manifested herself as a serpent (naag) at this location to a Pandit. According to the local legend, one Pandit Govind Joo Gadru had a vision of the serpent goddess who revealed the spot to him in dream. The Brahmin then arranged a boat and rowed through the marshy lands of Tulmul carrying a vessel of milk. Upon discovering the spot revealed by the goddess, he pored out the milk. Soon afterward, Kashmiri Pandit, one Krishna Taplu, had the vision of the same serpent a goddess who led him to the same holy spot. As time passed, the spot, marked in the marshes by flags and staffs, slowly became popular among the Kashmiri Pandits. The goddess became known as Rajni (Empress), Maharajini(The Great Empress), Tripurasundari (the same deity at Hari Parbat), Bhuvaneshwari and most famously as Khir Bhawani. The last name because it became the religious practice for the people to pour into the spring a dessert called Khir made of rice, sugar and milk.

In this drawing we can see Pandit men and woman sitting, surrounded by chinar trees, around the sacred spring (not visible but its end corner marked by flags and staffs*). The scared spring (naag) is believed to be the manifestation of an ancient goddess, who manifested herself as a serpent (naag) at this location to a Pandit. According to the local legend, one Pandit Govind Joo Gadru had a vision of the serpent goddess who revealed the spot to him in dream. The Brahmin then arranged a boat and rowed through the marshy lands of Tulmul carrying a vessel of milk. Upon discovering the spot revealed by the goddess, he pored out the milk. Soon afterward, Kashmiri Pandit, one Krishna Taplu, had the vision of the same serpent a goddess who led him to the same holy spot. As time passed, the spot, marked in the marshes by flags and staffs, slowly became popular among the Kashmiri Pandits. The goddess became known as Rajni (Empress), Maharajini(The Great Empress), Tripurasundari (the same deity at Hari Parbat), Bhuvaneshwari and most famously as Khir Bhawani. The last name because it became the religious practice for the people to pour into the spring a dessert called Khir made of rice, sugar and milk.

A temple was much later built on the island under the Dogra rule of Ranbir Singh(1830 -1885) and his son Pratap Singh (r. 1885-1924). Also, a goddess idol and a Shiva linga ( both believed to have been found in the waters of the spring) together were installed in a high chamber built inside the spring. A Shiv Linga and an idol of Goddess together cannot be found in any other hindu holy place. The work on temple was completed in the time of Maharaja Pratap Singh in 1920s.

Earlier in 1888 , British Land Settlement Commissioner to Kashmir, Walter Lawrence wrote about this place:

Khir Bhawani is their favourite goddess, and perhaps the most sacred place in Kashmir is the Khir Bhawani; spring of Khir Bhawani at the mouth of the Sind valley. There are other springs sacred to this goddess, whose cult is said to have been introduced from Ceylon. At each there is the same curious superstition that the water of the springs changes colour. When I saw the great spring of Khir Bhawani at Tula Mula, the water had a violet tinge, but when famine or cholera is imminent the water assumes a black hue. The peculiarity of Khir Bhawani, the milk goddess, is that the Hindus must abstain from meat on the days when they visit her. and their offerings are sugar, milk-rice, and flowers. At Sharka Devi on Hari Parbat and at Jawala Mukhi in Krihu the livers and hearts of sheep are offered. There is hardly a river, spring, or hill-side in Kashmir that is not holy’ to the Hindus,and it would require endless space if I were to attempt to give a list of places famous and dear to all Hindus. Generally speaking, and excluding the Tula Mula spring, which is badly situated in a swamp, it may be said that the Hindu in choosing his holy places had an eye for scenery, since most of the sacred Asthans and Tiraths are surrounded by lovely objects.

Interestingly, just around the start of the 20th century, Maharaja Pratab Singh, weary of curious European visitors who insisted on walking on the island with their shoes on and who fished in the sacred river waters surrounding the island, issued government decrees putting a check on their movement to this shrine.

Today, there is no historical account to inform us whether William Carpenter Junior had his shoes on or off while he visited the spring of Khir Bhawani and worked on those beautiful drawings.

-0-

Found these old images (albeit no mention of Khir Bhawani there) at the great resource columbia.edu

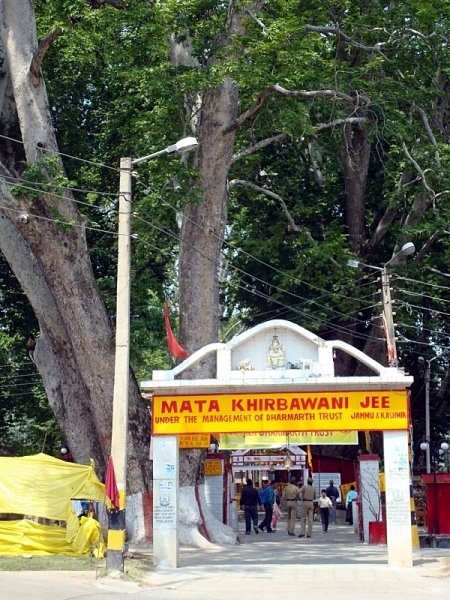

Rest of the photographs were taken by me in June 2008.

Photograph 1: A Hindu pilgrim, silently reciting some scripture, standing on one leg (with a little support) in water of the stream surrounding the island. I came back two hours later and he was still there.

Photograph 2: The view of the holy spring, flags, chinar trees and recently tiled ground of the island.

-0-

*Flags and Staffs: Walter Lawrence, in the aftermath of great flood of 1893 in Kashmir, recorded a curious practice prevalent among Kashmiri people. He wrote, ‘Marvellous tales were told of the efficacy of the flags of saints which had been set up to arrest the floods, and the people believe that the rice-fields of Tulamula and the bridge of Sumbal were saved by the presence of these flags, which were taken from the shrines as a last resort.’

-0-

For more about Kheer Bhawani, you can read the book ‘A Goddess is Born: The Emergence of Khir Bhavani in Kashmir’ By Dr. Madhu Bazaz

In this drawing we can see Pandit men and woman sitting, surrounded by chinar trees, around the sacred spring (not visible but its end corner marked by flags and staffs*). The scared spring (naag) is believed to be the manifestation of an ancient goddess, who manifested herself as a serpent (naag) at this location to a Pandit. According to the local legend, one Pandit Govind Joo Gadru had a vision of the serpent goddess who revealed the spot to him in dream. The Brahmin then arranged a boat and rowed through the marshy lands of Tulmul carrying a vessel of milk. Upon discovering the spot revealed by the goddess, he pored out the milk. Soon afterward, Kashmiri Pandit, one Krishna Taplu, had the vision of the same serpent a goddess who led him to the same holy spot. As time passed, the spot, marked in the marshes by flags and staffs, slowly became popular among the Kashmiri Pandits. The goddess became known as Rajni (Empress), Maharajini(The Great Empress), Tripurasundari (the same deity at Hari Parbat), Bhuvaneshwari and most famously as Khir Bhawani. The last name because it became the religious practice for the people to pour into the spring a dessert called Khir made of rice, sugar and milk.

In this drawing we can see Pandit men and woman sitting, surrounded by chinar trees, around the sacred spring (not visible but its end corner marked by flags and staffs*). The scared spring (naag) is believed to be the manifestation of an ancient goddess, who manifested herself as a serpent (naag) at this location to a Pandit. According to the local legend, one Pandit Govind Joo Gadru had a vision of the serpent goddess who revealed the spot to him in dream. The Brahmin then arranged a boat and rowed through the marshy lands of Tulmul carrying a vessel of milk. Upon discovering the spot revealed by the goddess, he pored out the milk. Soon afterward, Kashmiri Pandit, one Krishna Taplu, had the vision of the same serpent a goddess who led him to the same holy spot. As time passed, the spot, marked in the marshes by flags and staffs, slowly became popular among the Kashmiri Pandits. The goddess became known as Rajni (Empress), Maharajini(The Great Empress), Tripurasundari (the same deity at Hari Parbat), Bhuvaneshwari and most famously as Khir Bhawani. The last name because it became the religious practice for the people to pour into the spring a dessert called Khir made of rice, sugar and milk.

Sabziwol, Vegetable Seller at Hazratbal

Sabziwol, Vegetable Seller at Hazratbal